Pontoon Bridges: The Great Crossings

Yesterday Sarah Kay Bierle looked at the ancient uses of pontoon bridges and its perspectives on the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg. While she addressed the difficulties of bridging rivers, I would like to look at the other side of the coin: the most successful river crossings in the past 155 years.

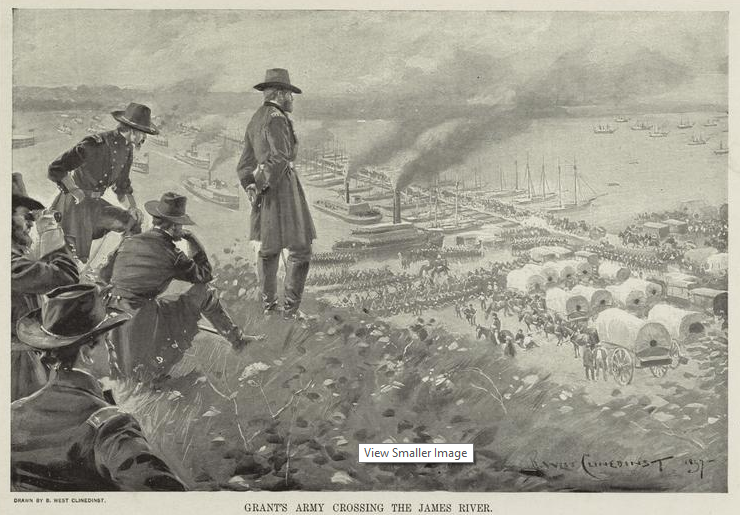

Students of the Civil War are no doubt familiar with the 1864 Overland Campaign and its  bloody battles between the Federal forces under U.S. Grant and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. But one aspect sometimes gets overlooked: the Federal crossing of the James River by ferry and bridge between June 13 and 17, 1864. The movement involved over 100,000 men, 5,000 vehicles, and 58,000 animals. Some moved by steamer and ferry, while two corps and the support elements of Grant’s forces crossed via a 2,200-foot pontoon bridge over the James, which is tidal at that point. This crossing was a triumph of logistics; the bridge over the James ranks as the longest pontoon bridge in military history.

bloody battles between the Federal forces under U.S. Grant and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. But one aspect sometimes gets overlooked: the Federal crossing of the James River by ferry and bridge between June 13 and 17, 1864. The movement involved over 100,000 men, 5,000 vehicles, and 58,000 animals. Some moved by steamer and ferry, while two corps and the support elements of Grant’s forces crossed via a 2,200-foot pontoon bridge over the James, which is tidal at that point. This crossing was a triumph of logistics; the bridge over the James ranks as the longest pontoon bridge in military history.

This last statement may strike some as erroneous – the British bridge over Burma’s  Chindwin River in December 1944 is often billed as the longest in military history. But that Bailey Bridge totaled only 1,600 feet including approaches; it was the longest Bailey Bridge built up to that time and was so reported in the press.

Chindwin River in December 1944 is often billed as the longest in military history. But that Bailey Bridge totaled only 1,600 feet including approaches; it was the longest Bailey Bridge built up to that time and was so reported in the press.

But even the Chindwin bridge wasn’t the longest Bailey Bridge in history. That honor goes to the 1,800-foot crossing of the Rhine built by Canadian and American engineers in March 1945.

Honorable mention must go to Sir William Slim’s Fourteenth Army with its crossing of Burma’s Irrawaddy River in February-March 1945. Too deep and swift to bridge, and ranging in width from 1.5 to 3.2 miles, the British and Indian troops used ferry operations and airlift to get across and press toward Mandalay.

These comparison cases from World War II only serve to highlight the Federal achievement of 1864 – an insufficiently-heralded moment in military history.

Top Image: Grant watches the crossing of the James, 1864.

Upper Middle: The Chindwin River Bridge, 1944.

Lower Middle: The Rhine River Bridge, March 1945.

Below: VIPs cross the Rhine Bridge, March 28, 1945. Left to right: Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, CIGS; British Prime Minister Winston Churchill; Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, commander of 21 Army Group; and Lieutenant General William H. Simpson, commander of U.S. Ninth Army.

I think Grant’s crossing of the Tennessee at Chattanooga, thanks in large part to Hazen’s advance strike force, was a great example, too, although the crossing of the James dwarfed it by all measures!

There is a wonderful article on the 1864 James River Crossing in Engineer Magazine, September-December 2009. Part of our tour kit for our battlefield tour of Petersburg

and Appomattox in 2011.

Bob Stoller Past President, Chicago Civil War Round Table

I’m curious as to where all the pontoon boats and planks came from?

Bridging equipment was often attached to the Army of the Potomac in anticipation of its immediate use, like before the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862. Engineer units maintained the equipment and placed the bridges.

At Chattanooga in October 1863, everything was fabricated locally, including the boats, by the Michigan Engineers with support from infantry regiments detailed to the engineers, including my great-grandfather’s regiment, the 21st Michigan. They cut the timber, milled logs into boards, and caulked the boats with cotton. For the Brown’s Ferry operation, they floated Hazen’s landing force down the river in the pontoon boats, and once the amphibious forces were landed before first light, used the boats to support the bridge built with lumber hauled by wagons overnight across Moccasin Bend.

Thank you for your response, Ted. That was an amazing operation to pull off without all the machinery we have today. Good old man and horsepower! Congrats on being a descendant of such an admirable man. I really appreciate you taking the time to enlighten me. Stay safe! Dave