East Tennessee and Confederate Copper

On November 25, 1863, Colonel Eli Long rode into Cleveland, Tennessee, at the head of 1,500 Union cavalrymen. They were there to wreak general havoc.

When it comes to Civil War cavalry raids, Long’s Cleveland incursion does not garner much attention. It was not a spectacular bit of insolence, like J.E. B. Stuart’s Ride around McClellan (well-covered by the press at the time) or of extreme duration, such as John Hunt Morgan’s disastrous jaunt across Indiana and Ohio. Long’s expedition lasted only four days and traveled barely 30 miles.

And yet it was one of the more successful raids of the war, undertaken in support of Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s full-scale assault on the Confederate Army of Tennessee atop Missionary Ridge. Long’s primary mission was to damage and disrupt the railroads all he could, thus ensuring that James Longstreet’s 20,000 Confederate troops in East Tennessee could not return to Missionary Ridge or effect a speedy junction with Braxton Bragg’s army somewhere in northern Georgia.

For two days Long’s troopers tore up miles of track, bending the upended rails atop piles of blazing crossties; an d ripped down all the telegraph wire they could find.

d ripped down all the telegraph wire they could find.

Communications between Longstreet and Bragg were effectively severed, completely fulfilling Grant’s expectations.

Of course, the town was hard used – as was most any town in the path of a Civil War army, no matter what color the uniforms. “A raid of Yankees came in this eve,” wrote 18-year-old Myra Inman, who lived on North street, two blocks east of the Bradley County Courthouse.

“They took two hogsheads of our corn . . . and are all over in everything else. We go to bed with sad hearts” Things soon grew worse. The next, day, she wrote, “the Yankees are taking our corn, potatoes pork, salt, and never pay a cent and besides talk very insulting to us. . . . [I]t is so hard to see it done and can’t help our selves. They burnt Mr. Raht’s wagon and the railroad and some cars. . . . Oh, how I wish I had power.”

Col. Long’s official report acknowledged considerable injury, though he focused more on itemizing seized public property: “In Cleveland I found a considerable lot of rockets and shells, large quantities of corn, and several bales of new grain sacks, all belonging to the rebel Government.” (Miss Myra doubtless would have disputed the ownership of the corn.) Almost as an aside, Long added that he “burned several railroad cars found here; also the large copper rolling mill – the only one of its kind in the Confederacy.”

Initially, the Federals seemed to care little about the rolling mill, which, viewed from a modern perspective, is interesting – copper was a vital war material, and Cleveland was just about the South’s sole source for that material. In modern war, that mill would be a critical infrastructure target.

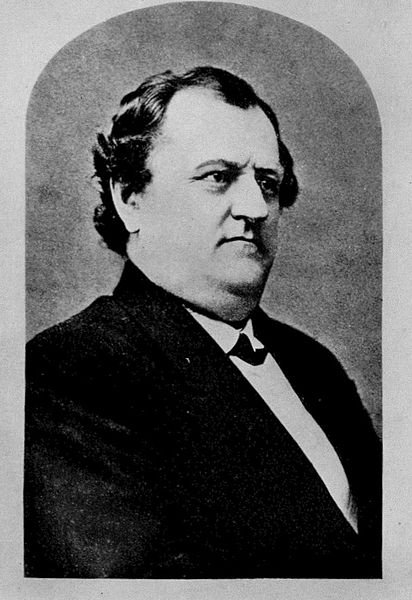

The mill came into being in early 1861, built to service the local copper industry. Copper ore was plentiful in the nearby Ducktown basin, over in Polk County, just 20 miles away. The man who operated those mines and built the mill, Julius Eckhardt Raht, was a German Émigré. Arriving in the United States in 1850, after the revolutionary upheavals of the late 1840s, Raht became a US Citizen in 1853. By 1861 he was a wealthy man, a part-owner in the operation and the manager for his remaining investors in New York and New Orleans.

The new Confederacy recognized the importance of both mines and mill. The Sequestration Act, gave the Confederate Government the power to seize the assets of anyone failing to declare their loyalty to the new country. Raht, no secessionist, refused to swear. Accordingly the mines and newly constructed mill were confiscated. The stock would eventually be re-sold to Confederate buyers in June 1863.

Raht nevertheless stayed on to run the operation, hoping to protect what he could of his and his investors’ property. This uneasy relationship continued until Col. Long arrived.

Copper was essential for the production of bronze cannon and useful for all sorts of other material (telegraph wire, for example) but it was most critical for use in rifle and pistol percussion caps. Large thinly rolled sheets of copper were the main component of those caps. Cleveland was the only place in the South where those sheets could be produced. Long might not have been sent expressly to destroy the rolling mill, but once there, he could not leave it intact.

The discovery in town of some cylindrical “torpedoes” (the rockets Long mentioned) only added to the destruction. These seem to have been land or sea mines of the type offended Yankees labeled “infernal devices,” used as a form of covert warfare, but descriptions are unclear. They were also apparently already loaded with powder, for when Long ordered them piled in the rolling mill before setting it afire they exploded in spectacular fashion. Unionist East Tennessean J. S. Hurlburt described them:

“As soon as the flames reached the torpedoes, they exploded in every direction whirling and hissing through the air in the most dangerous and terrific manner conceivable. In the space of half an hour, upwards of sixteen hundred of these nameless, nondescript, rebel inventions burnt themselves loose from the fiery mass, going off with a successive, rattling, crashing noise and thundering cannon-like explosions . . .”

The Confederates got a small bit of their own back when John H. Kelly and about 500 Confederate cavalry swept into town the next morning, catching some of the Federals by surprise. Kelly had a section of artillery along, and that support soon convinced Col. Long that he was outmatched. The Federals retreated. Miss Inman was pleased, noting that “our forces attacked Gen. Long’s forces, 13 hundred strong, and whipped them. We had 2 cannon and a howitzer, 2 or 3 killed on both sides, several wounded.” The battle left her “joyous,” but that emotion was short-lived. Kelly’s Rebels left town almost as quickly as Long’s men skedaddled. Bragg’s defeat at Missionary Ridge made it impossible for them to stay.

Long returned to Chattanooga, but within a few days, the Federals were back; this time for good. Federal infantry, including the 9th Indiana regiment, wintered around Cleveland, restoring the railroads and firming up Union control over East Tennessee. Other Federals would move in in the summer of 1864, replacing those troops headed south on Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Though they never rebuilt the rolling mill or resumed copper mining in Ducktown, the resource remained denied to the Confederacy for the rest of the war. Julius Raht, with no investment left to protect, traveled to Cincinnati to wait out the fighting. He would return in 1866, regain control of his mining interests, and rebuild his fortunes. His re-opened mines produced more than One million pounds of copper in the first full year after the end of the war.

And what of Confederate copper? The loss of the mines and mill had an immediate effect. In a postwar account, William LeRoy Broun, who headed up the Confederate Arsenal in Richmond, recalled that “the casting of bronze field guns was immediately suspended, and all available copper was carefully hoarded for the manufacture of caps. It soon became apparent that the supply would be exhausted and the armies rendered useless unless other sources of supply could be obtained.” The blockade had effectively choked off imports, Broun noted, leaving only one last resort: “copper turpentine and apple brandy stills which still existed in North Carolina in large numbers.”

“Secretly . . . an officer was dispatched . . . to purchase or impound all copper stills found available, and ship the same, cut into strips, to the Richmond Arsenal.”

“And thus were all the caps issued from the arsenal and used by the armies . . . during the last twelve months of the war manufactured from the copper stills of North Carolina.”

Which leads us to the next question: What was done about the resultant Apple Brandy Crisis of 1864?

Well, that left only branch water in which to drown Confederate sorrows, I guess.

It was a forgotten tragedy. I do declayah.

Very interesting story. I loved the detail and factoids, the story of the fate of the copper stills, especially.

He also bagged the baggage train of William Wright’s Tennessee Brigade who had been sent towards Knoxville, got to Cleveland and were recalled to Chattanooga. The troops made it back in time for Missionary Ridge but their wagons did not.

My bad – it was Marcus Wright. Long’s and his OR reports both state that his trains were smashed and captured.

Dave, Very well written and obviously, well researched. Never heard of it until you mentioned it as part of a Chickamauga presentation. Thanks for your research. Frank