A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 3

(Part 1 and Part 2 are available.)

So why was Ord’s idea even considered, and actually supported, at the highest levels of a Confederate government steeped in a patriarchal culture? Porter offered an answer in that “it must be remembered that the condition of the Confederacy was then desperate, and that drowning men catch at straws.” Nevertheless, only seventeen years after the first Women’s Rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, which helped to launch the women’s rights movement in America, a peace conference with women in prominent roles would have been truly revolutionary—“visionary” in Porter’s words. And yet, it almost happened.[1]

It is interesting to think what Longstreet’s initial response to this “visionary” plan was. Years later he said, “I was much pleased with the proposition,” and his wife “was anxious to do her part in the plea for peace, and was very soon ready to start upon her delicate but interesting errand.” Longstreet acknowledged the limitations of his position though, and simply told Ord that he “was not authorized to speak on the subject, but could report upon it to General Lee and the Confederate authorities, and would give notice in case a reply could be made.”[2]

On Sunday, February 26, Lee and Longstreet met with President Davis and Confederate Secretary of War, John C. Breckenridge, for several hours at the Executive Mansion in Richmond to discuss Ord’s proposal. All except Davis believed the war was essentially over and therefore they needed to find a path to peace. Even General Lee believed they were fighting for a “hopeless” cause, but Davis still refused to entertain any thoughts of restoring the Union. Still, the Confederate president was willing to support a military convention, believing that it might somehow lead to southern independence, although no one else at the gathering that night agreed with that assessment. Nonetheless, Davis authorized Lee to open negotiations with Grant. Longstreet acknowledged that Breckenridge, in particular, “expressed especial approval of the part assigned for the ladies.” The Confederates did not waste any time, for the next step seemed clear. “A telegram was sent my wife that night at Lynchburg calling her to Richmond,” Longstreet recalled, “and the next day a note was sent General Ord asking him to appoint a time for another meeting,” ostensibly to discuss prisoner exchanges. In the note, Longstreet also mentioned that “if possible, I would be pleased to meet Lieutenant-General Grant at the same time and place on the same subject.” [3]

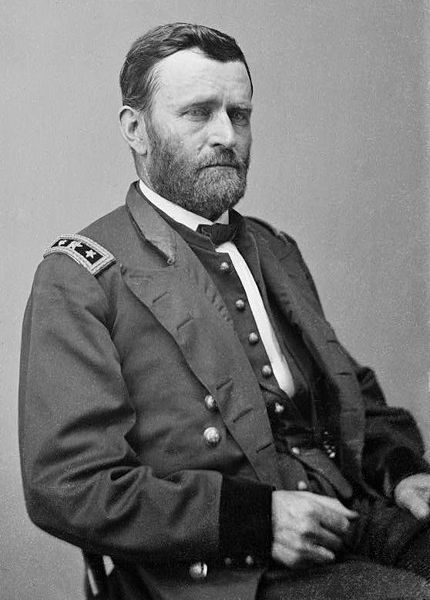

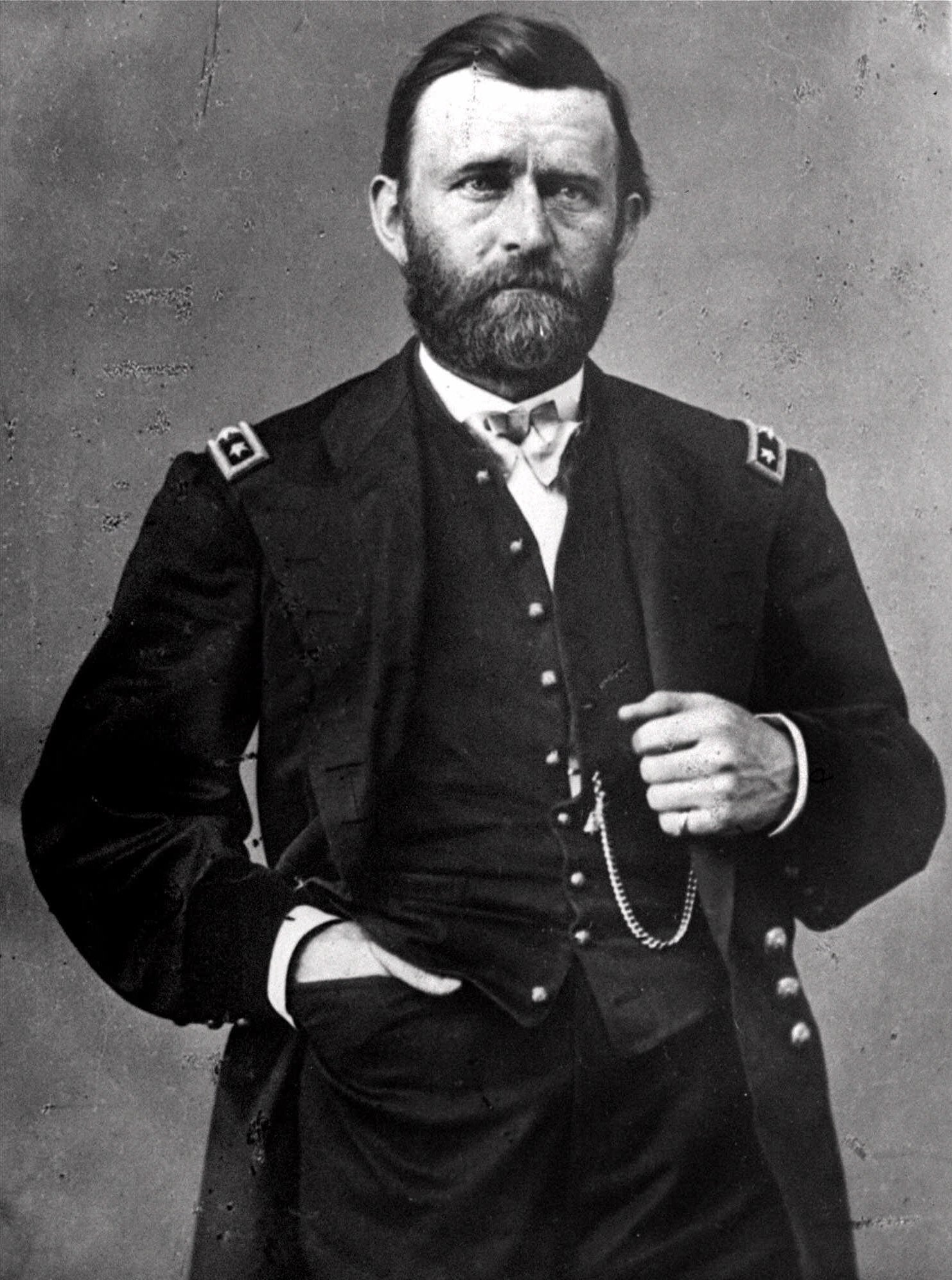

Grant wanted to meet with Longstreet himself, someone he had known very well and trusted, perhaps to find out what was going on behind Confederate lines from a reliable source on the inside. Grant and Longstreet had been close friends from their first meeting at West Point over twenty years before. They had served together in the Fourth Infantry at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, fought together in the Mexican War, and remained friends thereafter. Longstreet was also a groomsman at Grant’s wedding in 1848 (some say he was the best man), and the marriage made Grant a kinsman as well, since Julia Dent Grant was Longstreet’s cousin. Like Ord, he may have thought he could persuade Longstreet to work with Lee to influence President Davis and begin a process that might lead to peace. Ord told Grant that Longstreet “was impressed with the truth of my views . . . to try and convince Genl Lee—and through him Genl Davis, the Presid. of the Confed—of the great wrong of subjecting the South to further bloodshed.” Ord also mentioned that he asked Longstreet why they were still holding out. Longstreet was just as anxious as Ord to stop the fighting, and replied that while “it was a great crime against the Southern people and Army” to continue to engage in “hopeless and unnecessary butchery,” the problem was that “Davis was the great obstacle to peace.” But while Grant admitted to Ord that he “should like to meet” with Longstreet, he realized that “it probably will be better for you to have another interview . . . before I agree to meet him.”[4]

Throughout this period, Grant was “anxious” for peace, according to William McFeely, especially because he feared what would happen if the Confederate army switched to guerrilla tactics, thus forcing him to relinquish what control he had over the situation. McFeely argues that “Grant’s eagerness to bring the politicians to the table” at Hampton Roads had stemmed from his belief that “the peace conference had a chance of succeeding,” and that somehow “Lincoln and the three Confederates would find a way to say that enough was enough.” In his memoirs, Grant acknowledged that he had met with the Hampton Roads commissioners “frequently” while they were awaiting their meeting with Lincoln, and “found them all very agreeable gentlemen.” He also stated, however, that he had “no recollection of having had any conversation whatever with them on the subject of their mission. It was something I had nothing to do with, and I therefore did not wish to express any views on the subject. For my own part I never had admitted . . . that they were the representatives of a government. There had been too great a waste of blood and treasure to concede anything of the kind.” In other words, while he had worked assiduously to create the environment for what became the Hampton Roads peace conference, he was also quick to note that he played no part in the actual negotiations.[5]

Even though the Hampton Roads conference had failed, Grant still believed there would be other opportunities for opening the road to peace. “Every thing looks to me to be very favorable for a speedy termination of the war,” he wrote in mid-February. “The people of the South are ready for it if they can get clear of their leaders.” He thought that if southern politicians could not agree to the terms that Lincoln had proposed at the recent conference, which Julia told the president “were most liberal,” then maybe “the people will forcibly depose them and take the matter into their own hands.” Grant was clearly aware of a recent letter that Secretary of State William Seward received regarding the views of former Mississippi Senator Henry S. Foote, an ardent foe of Davis, in that many southern leaders were prepared “that if peace was not restored . . . they would in defiance of Davis and the War faction stump their respective states for an immediate reunion with the Federal States.”[6]

It is unlikely, however, that Ord acted on his own without Grant’s knowledge of at least some aspects of the plan. Historian Brooks Simpson argues that “Grant was aware that Ord had been talking to Longstreet, but he was not sure how serious was the offer to negotiate.” It appears that Grant supported a general discussion among the leading officers, as Ord had proposed, perhaps believing that it might generate an atmosphere conducive to eventual negotiations that could lead to the surrender of the Confederate armies. If one believes war correspondent Sylvanus Cadwallader’s observations, this was a distinct possibility. He claimed that when Grant and Lee met in the morning of April 10 at Appomattox, “Lee stated that if Grant had assented to a meeting which he had proposed some weeks before, peace would undoubtedly have resulted there-from.” Although unlike the Hampton Roads conference, Grant would have been a central participant in the actual proceedings in March, such as he was at Appomattox a month later.[7]

Perhaps Grant also believed that Lincoln might reconsider the military convention if the officers could “talk a little,” as Ord had suggested, and see if there was an acceptable path for them to pursue that would finally end the war in March without another battle. It was worth a try, especially as Grant became more concerned that Lee would disappear south and the war would drag on. But while Grant does not mention the proposed March conference in his memoirs, he confessed that

One of the most anxious periods of my experience during the rebellion was the last few weeks before Petersburg. I felt that the situation of the Confederate army was such that they would try to make an escape at the earliest practicable moment, and I was afraid, every morning, that I would awake from my sleep to hear that Lee had gone . . . and the war might be prolonged another year.

I was led to this fear by the fact that I could not see how it was possible for the Confederates to hold out much longer where they were.[8]

Grant also worried that “anything that could have prolonged the war a year beyond the time that it did finally close, would probably have exhausted the North to such an extent that they might then have abandoned the contest and agreed to separation.”[9]

To be continued…

[1] Ibid., 392.

[2] Frank A. Burr, “Grant to Longstreet,” The Philadelphia Times, May 15, 1892; Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 584.

[3] The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, February 21-April 30, 1865, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale, 1985), 14:64; Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox, 584; James Longstreet to Edward O. C. Ord, February 27, 1865, U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C., 1888-1904), Series II, 8, 315. Longstreet mentioned in his memoirs that he met with Ord on February 21 (see From Manassas to Appomattox, 583-584), but in this letter, he refers to their meeting on Feb. 25. See also Sanger and Hay, James Longstreet, 288.

[4] The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 14:63-64; Ulysses S. Grant to Edward O.C. Ord, February 27, 1865, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 14:63.

[5] William S. McFeely, Grant: A Biography (New York, 1982), 208-209; Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (1885; New York, 1982), 522-523; Ibid., 384. Stephens corroborated this, noting that Grant was “exceedingly anxious for a termination of our war,” and that while the commissioners waited at City Point for Lincoln’s next move, Grant “met us frequently, and conversed freely upon various subjects, not much upon our mission.” See Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, 597-598.

[6] U.S. Grant to Isaac N. Morris, February 15, 1865, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 13:429; Julia Dent Grant, The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant) ed. John Y. Simon. (Carbondale, 1975), 138; U.S. Grant to Isaac N. Morris, February 15, 1865, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 13:429; W.N. Bilbo to William H. Seward, February 14, 1865, U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C., 1888-1904), Series I, 46(2), 561.

[7] Brooks D. Simpson, Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861-1868 (Chapel Hill, 1991), 76; Sylvanus Cadwallader, Three Years with Grant as Recalled by War Correspondent Sylvanus Cadwallader, ed. Benjamin P. Thomas (Lincoln, 1996), 334.

[8] Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, 525.

[9] Ibid., 384.

1 Response to A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 3