A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 4

(Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 are available.)

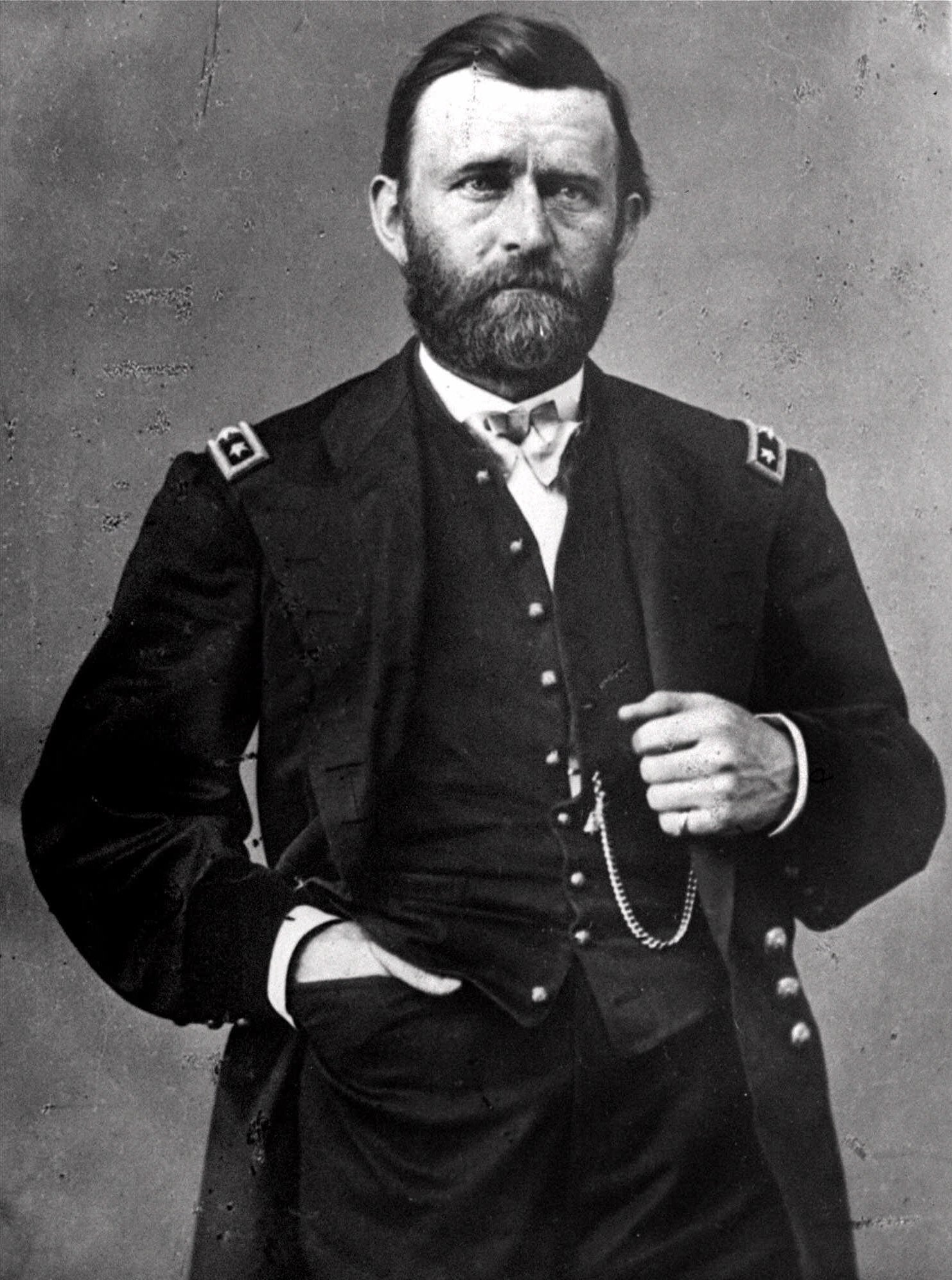

It is important to note that although Grant seemed somewhat hopeful that the military leaders could “talk a little” about resolving the conflict, he did not support Ord’s proposal for including Julia in the process. Instead, this “visionary” part of the plan was clearly Ord’s idea, wholly supported by Longstreet who was eager to put it into effect. The first step was to obtain permission for Louise Longstreet to pass through Union lines. But even this was done with a bit of subterfuge. Grant told Ord that “if Longstreet wishes to send his family North, to stay, they will be received at my Hd Qrs. and sent where he wishes. I do not think he would concent [sic] to send them here to return again. If however he will let them come, even to go back again you may let them come.” It is doubtful, though, that Longstreet actually wanted “to send his family North, to stay.” Instead, it seems as if Ord had begun putting his plan in motion with Longstreet’s help by seeking approval for Louise Longstreet to cross Union lines. For by passing through Grant’s headquarters first, Louise would inevitably run into Julia.[1]

As the two men were discussing the situation, Julia happened to enter the room. She recounted the event in her memoirs:

Late one afternoon, about four o’clock, not long before the last move toward Richmond, I entered from my bedroom General Grant’s office, where I found General Grant in conversation with General Ord. General Grant said to me: “See here, Mrs. Grant, what do you think of this? Ord has been across the lines on a flag of truce and brings a suggestion that terms of peace may be reached through you, and a suggestion of an interchange of social visits between you and Mrs. Longstreet and others when the subject of peace may be discussed, and you ladies may become the mediums of peace.” At once, I exclaimed: “Oh! How enchanting, how thrilling! Oh, Ulys, I may go, may I not?” He only smiled at my enthusiasm and said: ‘No, I think not.’ I then approached him, saying, “Yes, I must. Do say yes. I so much wish to go. Do let me go.” But he still said: “No, that would never do.” Besides, he did not feel sure that he could trust me; with the desire I always had shown for having a voice in great affairs, he was afraid I might urge some policy that the President would not sanction. I replied to this: “Oh, nonsense. Do not talk so, but let me go. I should be so enchanted to have a voice in this great matter. I must go. I will. Do say I may go.” But General Grant grew very earnest now and said: “No, you must not. It is simply absurd. The men have fought this war and the men will finish it.”

I urged no more, knowing this was final, and I was silent, indignant, and disappointed. Then I turned to General Ord and inquired how such an idea could have been suggested. He told me he had gone over on a flag of truce, saying our men and the rebs were exchanging papers, tobacco, even running races, and on good terms apparently, and he thought it was high time this was stopped. After settling this little matter, Ord said: “I said to Longstreet, ‘Why do you fellows hold out any longer? You know you cannot succeed. Why prolong this unholy struggle? Every day you hold out you are worsting yourselves.’” I think General Ord said he had proposed the ladies as a medium of peace—he was always kind—but this I do know: such a proposition never emanated from General Grant.[2]

Julia knew her husband well enough to know that he would never have proposed a parallel encounter for her and Louise Longstreet. Julia was whip-smart and socially refined, but she could be a little too open and trusting, occasionally advocating positions that might be awkward for her husband, and also taking pity on people who perhaps did not deserve it. There were many times during the war when she had petitioned her husband for the relief of a poor soul seeking Grant’s mercy for one reason or another, sometimes against his better judgment. In one instance near the end of the war, for example, a teary-eyed, soon-to-be widow, successfully sought Julia’s help in getting a pardon for her husband who was facing death due to desertion. Even though he originally said, “I cannot interfere,” Grant eventually gave in, and then told Julia afterward, “I’m sure I did wrong. I’ve no doubt I have pardoned a bounty jumper who ought to have been hanged.” On another occasion, Julia tried counseling her husband on the proper course for the Vicksburg campaign, to which he replied, “I am afraid your plan would involve great loss of life and not insure success. Therefore, I cannot adopt it.” But he consoled his wife by pointing out that it would “all come out right in good time.” Thus, Grant knew there was a real possibility that she might take a position that would not only be difficult for him, but even worse, could put her at odds with the Lincoln administration, a point she herself acknowledged.[3]

On the other side, little is known about Louise Longstreet. She was the daughter of General John Garland, Grant and Longstreet’s former brigade commander in the old army, and was a dedicated military wife and mother. Variously described as “vivacious,” and “a woman of remarkable strength of character,” Louise Longstreet was “quite proud of the general,” and fiercely protective of her family. Regarding the peace conference, however, there is only her husband’s brief mention of her thoughts regarding the proposal, as most of the family papers were destroyed in a house fire on the anniversary of Appomattox in 1889.[4]

To be continued…

[1] Ulysses S. Grant to Edward O.C. Ord, February 24, 1865, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 14:34-35.

[2] Grant, The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant, 141.

[3] Ibid., 133, 111.

[4] “Longstreet in Peace,” The Galveston Daily News, August 7, 1887; “Death of Mrs. Longstreet,” The Florence (Alabama) Herald, January 4, 1890; “Longstreet in Peace.”

1 Response to A “Visionary” Plan? The Proposed March 1865 Peace Conference, Part 4