Mexican-American War 170th: Battle of Huamantla

After almost a month of siege, the American garrison inside the city of Puebla still held on. They continued to resist Mexican attacks, but their situation was growing dire. Help, though, was on its way. Brigadier Gen. Joseph Lane’s brigade of counter-guerrilla soldiers were marching to Puebla’s relief.

But before Lane’s men could get to Puebla, they would have to face off against Santa Anna, who took most of his forces to cut short Lane’s relief expedition. Waiting for Lane to come, Santa Anna put most of his men inside the small town of Huamantla, about halfway to Puebla from where Lane’s Americans had started from. To get to Puebla, Lane would have to fight.

On the morning of Oct. 9, 1847, Lane’s brigade continued its march to Puebla. As the day grew hotter and hotter, Lane soon found out that Santa Anna was waiting with about 2,000 men. With some 1,700 soldiers at his command, Lane left behind a detachment to guard his wagons and sent four companies of cavalry ahead to recon the village.[1]

The four companies of mounted Americans, about 250 men total, were headed by Capt. Samuel Walker and the famed Texas Rangers. Walker, originally from Maryland, had made quite a name for himself fighting since the early 1840s. His fighting reputation left one to write, “war was his element, the bivouac his delight, and the battlefield his playground.” In his belt, Walker carried a pistol that bore his name—the Walker Colt Pistol, created alongside the famed Samuel Colt. With its six chambers, the pistol gave Walker plenty of firepower.[2]

As Walker’s mounted troopers neared Huamantla, he could see the Mexican defenders. Most of the soldiers were mounted Mexican lancers, and Walker likely figured he could disperse them with his overwhelming weaponry. Forming his troopers and Rangers, Walker ordered the Americans to charge without waiting for support from the rest of Lane’s column that was marching behind them.

Getting towards Huamantla, the Americans grouped together into a column of four riders abreast and rode into the town, when “rose a wild yell, and such a charge!”[3] Walker’s men streaked into the town, and the sudden ferocity of the cavalry attack pushed the stunned Mexican defenders back. In the quick melee, Walker’s men even managed to capture two Mexican artillery pieces, and worked to turn them on their previous owners.

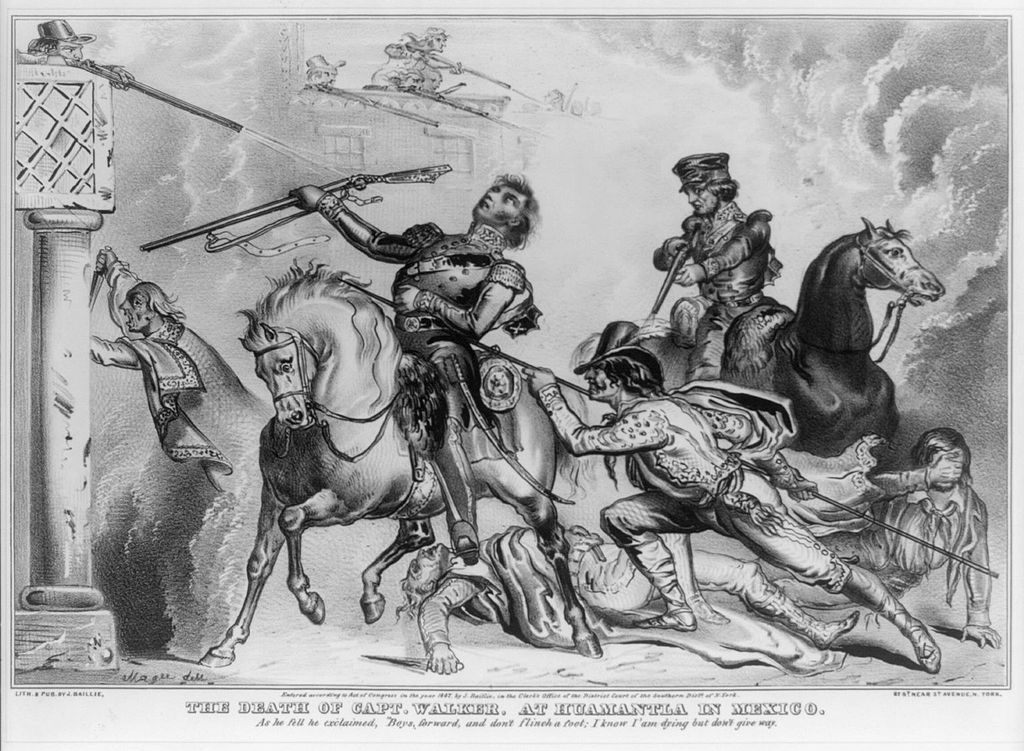

As the mad dash through the streets continued and the formal Mexican resistance broke, the inhabitants of Huamantla got involved in trying to repulse Walker’s men. And now the Americans found themselves cut off, having sliced through the town but separated from their supports in Lane’s main column. Musketry started to pop from windows and rooftops around the Americans. In that fire Walker went down.

Different stories have different tales of Samuel Walker’s death—some say a Mexican stabbed him with a lance, but others concretely state he was shot. An American soldier wrote Walker “was shot from behind, from a house that displayed a white flag.”[4] Captain Samuel Heintzelman, coming up with the main column, wrote that Walker had been “shot above the eye and in the right breast.”[5]

Samuel Walker’s death left his troopers reeling for safety. Most of the Americans dismounted and “took shelter in a church until the infantry arrived.”[6] Lane’s column reached Huamantla and pushed into the town, reaching the church and relieving the hard-pressed troopers. With Lane’s infantry on scene, Santa Anna’s Mexican forces retreated further out of town, effectively ending the battle. It was a quick affair, but resulted in 24 American losses and 400 Mexican casualties between killed, wounded, and captured.[7]

Though the battle was over, Huamantla’s ordeal was just starting. Angered by their commander’s death, many of Walker’s men began to sack the city. American soldiers “broke into houses and shops, took whatever they wanted, raped the women, and killed the men,” historian Timothy Johnson writes. “It was a drunken orgy of violence and destruction,” Johnson continues.[8] Captain Heintzelman tried to intercede, but wrote, “I could do nothing with them,” and Lieutenant A.P. Hill, who had missed the battle, added, “’Twas then I saw and felt how perfectly unmanageable were volunteers and how much harm they did.”[9]

Joseph Lane did nothing to stop the crimes, and many of his infantry joined the destruction. By the following morning hundreds of his soldiers were too drunk to do much of anything beneficial and when Lane formed his brigade to keep marching to Puebla, A.P. Hill fumed that “My arm was perfectly sore from beating the men into obedience [with] both fist and sword.”[10]

The episodes at Huamantla were some of the worst orchestrated by the American military during the Mexican War. It left a sour taste in the mouths of regular army officers like Samuel Heintzelman and A.P. Hill, who during the Civil War would find themselves commanding tens of thousands of volunteer soldiers, and who sought to make sure such events didn’t happen in their own ranks.

Three days after the battle, Lane’s men closed on Puebla and officially broke the siege. Thomas Childs’s garrison had held out, and Santa Anna’s forces broke away into the countryside. Capturing the city of Puebla had been Santa Anna’s last gambit for potentially making up for the fall of Mexico City, and it had failed. As historian Bruce Winders writes, “the Battle of Huamantla and the raising of the siege of Puebla ended serious organized resistance in Mexico.”[11]

Now it was a matter of what the politicians and diplomats could come up with.

______________________________________________________________

[1] K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974), 330-331.

[2] Nathan A. Jennings, Riding for the Lone Star: Frontier Cavalry and the Texas Way of War, 1822-1865 (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2016), 176.

[3] Niles National Register, “Battle of Huamantla, Death of the brave Captain Walker,” Nov. 27, 1847.

[4] Niles National Register, “Battle of Huamantla, Death of the brave Captain Walker,” Nov. 27, 1847.

[5] Jerry Thompson, Civil War to the Bloody End: The Life & Times of Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006), 27.

[6] Bauer, 331.

[7]Bruce Winders, “Huamantla, Battle of,” edited by Spencer C. Tucker, The Encyclopedia of the Mexican-American War: A Political, Social, and Military History (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO), 307.

[8] Timothy D. Johnson, A Gallant Little Army: The Mexico City Campaign (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 249.

[9] James I. Robertson, Jr. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior (Random House: New York, 1992), 15-16.

[10] Ibid., 16.

[11] Winders, 308.

In his memoirs, Santa Anna blamed all his mistakes, failures and defeats on subordinates. According to historians, Santa Anna had a weakness for logistics throughout his military career.

Curious to know your conclusions. Especially with regards to why Santa Anna was not as blessed as regional contemporaries, Simon Bolivar and Jose San Martin.

— Will Reardon

Hi Will,

Great question. I think Santa Anna had a lot of problems with the overall grand scheme of wars, as you allude to with logistics. He never had great staffs, and he was never capable of contending with armies that did.

His tactics during the Mexico City Campaign really weren’t that bad– his defenses at Cerro Gordo, for example, were top-notch. But, because of his lack of a greater staff, and because of the *constant* in-fighting between generals and the government, led to fissures that Santa Anna was unable to seal. Better armies exploited those fissures, leading to Santa Anna’s defeat.

Fascinating read !