Battlefield Markers & Monuments: Yorktown Monument – A Victim of Another War

It was early in the war, in the spring of 1862 when the armies converged on Yorktown, Virginia. The fact that many had not yet seen combat and been hardened to the realities of war, combined with the surge of patriotism at finding themselves at Yorktown, are reflected in numerous soldier’s accounts.

It was early in the war, in the spring of 1862 when the armies converged on Yorktown, Virginia. The fact that many had not yet seen combat and been hardened to the realities of war, combined with the surge of patriotism at finding themselves at Yorktown, are reflected in numerous soldier’s accounts.

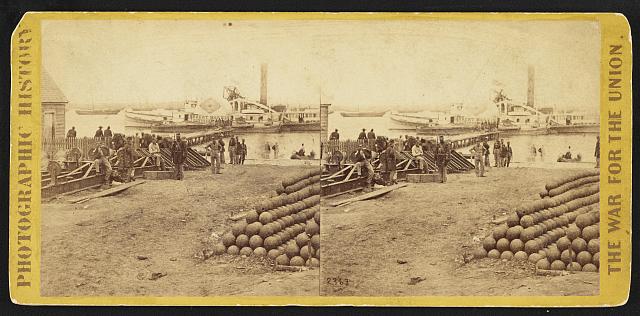

General George B. McClellan landed the Army of the Potomac at the tip of the Peninsula and began moving west, toward Richmond. Confederate forces led by General John B. Magruder prepared a series of fortifications to block their movements, one of which was anchored at Yorktown. By May the armies were in contact near the old port town.

While many of the articles in this series will discuss monuments placed on battlefields after the engagement, in this case Union and Confederate soldiers found something unique when they approached the old battlefield, there already was a monument here.

A small monument stood outside the town and it quickly became a focal point for Confederate, then Union troops. It was fourteen feet tall, and noted the site where General Charles O’Hara (acting in Cornwallis’s place) met Washington as the British and Hessian troops marched out to lay down their arms in October, 1781.

The obelisk stood south of town along the Hampton Road, where the Allied siege lines had once ran. It was here that Washington and Rochambeau, on behalf of the American and French armies, stood waiting to receive Cornwallis.

As the redcoats marched out of town towards them, American troops lined the east side of the road, and French soldiers on the west. Yet Cornwallis was not present, claiming illness. His second in command, General Charles O’Hara, attempted to offer his sword to General Rochambeau. The French officer, knowing that O’Hara would prefer to surrender to a fellow European, rather than the Americans, declined, and pointed him to Washington.[1]

Upon turning to the Virginian and offering his sword to Washington, O’Hara was pointed towards General Benjamin Lincoln. Since Cornwallis himself had not come, Washington insisted that O’Hara surrender to his second in command. There was also a bit of irony in that General Lincoln had been forced to surrender the city of Charleston, SC to the British the year before, and was now symbolically accepting the capitulation of those very troops.[2]

Following these formalities, the British, Hessian, and Loyalist troops of the garrison marched past the spot to an open field over a mile to the south, where they stacked their arms, flags, and military accoutrements.[3]

The site was of such significance that Virginia militia placed a monument here on October 19, 1860. It was a white marble obelisk resting on a base of two James River granite blocks. Temporary wooden and plaster victory arches were erected on the battlefield for Lafayette’s 1824 visit, which were only placed for that occasion.[4]

Many of the earthworks were torn down by French troops over the winter of 1781-2. Remnants survived when war came again in 1861. Confederate troops fortified Yorktown, using some of the remaining mounds of earth as a basis.[5]

With General George B. McClellan’s arrival on the Peninsula with the Army of the Potomac, Yorktown became a front line position. In late April and early May, 1862, both sides dug in and a siege ensued. Curious soldiers, knowing the significance of their location, gravitated to the spot of the general’s 1781 meeting and the monument. The details of understandings were often incorrect.

Only a handful of accounts describing or even mentioning the monument have surfaced. I am trying to collect others as I find them. For those soldiers of 1862, seeing the monument and reflecting on the event it commemorated had a deep impact.

Soldier W. H. Bird of the 13th Alabama wrote, “At Yorktown we saw many things to remind us of the terrible war between America and Great Britain, for it was here that Cornwallis surrendered to Washington, October 19, 1781. We saw some posts said to have been used by Washington’s army in building a bridge over a swamp. The spot where the sword of Cornwallis was surrendered is marked by a monument.”[6]

George Lee of the 4th North Carolina recalled, “We are exactly on the battle ground of Washington and Cornwallis, but all that remains to be seen are the old breastworks of the British, which lie immediately behind ours. The Yankees hold the same position that Washington did. There is also the place where Cornwallis surrendered his sword to Washington.”

Vines Edmund Turner wrote, “About the quaint old town were many points of interest that awakened patriotic contemplation. The marble slab half a mile from town, marking the spot where eighty years before Cornwallis had surrendered to Washington, was a favorite place of visitation.”[7]

S.H. Wright of the 2nd Florida noted, “About a mile from Y. is a monument that claims to mark the exact spot on which Cornwallis’ sword was surrendered, and relic hunting travelers have in consequence chipped away one large block of marble and are about to make this one disappear.”[8]

Robert Sneden of the 40th New York wrote, “The marble monument erected by Congress to commemorate the surrender of Cornwallis stood on the plateau a little off the main road leading from Hampton to Yorktown. It had been broken all up and carried off for relics by either our fellow or the Rebels. Only the foundation remained and if this not been too heavy to carry, would have been take also by the ‘relic hunting fiend.’”[9]

Unfortunately there is no known image of this monument, and it was chipped away and carried off by souvenir hunters until it was gone. One Union account claimed that it was “hacked to fragments by the Southerners, and carried away piecemeal.” The large monument now standing over Yorktown’s earthworks dates to 1887.[10]

Yorktown’s second siege is a window into this fascinating aspect of the war, where troops from both sides encountered tangible remains of the Revolution that had inspired their patriotism. Few other locations in the country had the sort of emotional connection and inspiration that Yorktown did.

For perhaps the only time in the war, the armies fought on ground where there already was a monument, and it unfortunately fell victim to their actions.

Sources

Bird, W. H. Stories of the Civil War. Columbiana, GA.

Bland, Scott Otis. The Yorktown Sesquicentennial. Washington; United States Yorktown Sesquicentennial Commission, 1932.

Chambers, Thomas. Memories of War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Greene, Jerome. Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report, The Allies at Yorktown: A Bicentennial History of the Siege of 1781. Denver: National Park Service, 1976.

Manley, Kathleen. A History of Yorktown and Its Celebrations. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2005.

Richmond National Battlefield Park Archives, Richmond, VA.

Sneden, Robert. Eye of the Storm. Ed. Charles Bryan, Jr. and Nelson D. Lankford. New York, 2000.

Turner, Edmund Vines Papers, quoted in John Quarstein and J. Michael Moore, Yorktown’s Civil War Siege. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012.

[1]Jerome Greene, Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report, The Allies at Yorktown: A Bicentennial History of the Siege of 1781 (Denver: National Park Service, 1976), 327.

[2] Ibid., 331.

[3] Ibid., 333.

[4] Thomas Chambers, Memories of War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), 180; Scott Otis Bland, The Yorktown Sesquicentennial (Washington; United States Yorktown Sesquicentennial Commission, 1932), 10-11; Kathleen Manley, A History of Yorktown and Its Celebrations (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2005), 19.

[5] Greene, 349-50.

[6] W. H. Bird, Stories of the Civil War (Columbiana, GA), 10.

[7] Edmund Vines Turner Papers, quoted in John Quarstein and J. Michael Moore, Yorktown’s Civil War Siege (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012).

[8] Richmond National Battlefield Park Archives, Richmond, VA.

[9] Robert Sneden, Eye of the Storm, Ed. Charles Bryan, Jr. and Nelson D. Lankford (New York, 2000), 61.

[10] Chambers, 181.

I read that during the Civil War Sesquicentennial Yorktown and Williamsburg both did some sort of interpretation of the events that impacted these Revolutionary War sites. I would love to know if someone knows anything about this. Thanks.

Meg, yes, Yorktown, Williamsburg, and other communities on the Peninsula commemorated the 150th of those events. I do not believe there was any specific interpretation of the Revolutionary-Civil War connections.

Interesting reading.

Thank you!

For many years they held a Civil War encampment every Memorial Day weekend to commemorate the Civil War history of Yorktown. It was held in the immediate area of the visitor’s center. I understand a couple years ago Park Service politics got it changed to a random weekend in April.

Hi Alton,

I don’t know much about that, but I do know that there has been a Civil War event in the park for years, and assume there still is. I don’t know any details of it.