Sea Power at Port Royal Sound: A Missed Opportunity?

On November 5, 1861, the Confederate Secretary of War established the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and East Florida as a military department, assigning one of his most senior and experienced officers, General R. E. Lee, to command it.

No Federal armies were marching anywhere near that far south. The threat was from the sea, from the dangerous flexibility overwhelming command of the sea provided their adversaries. The general was to consolidate scarce resources and improve defenses along that vital coast.

Lee warned from Savannah in January 1862: “The forces of the enemy are accumulating, and apparently increase faster than ours.” He feared, given maritime capabilities of speedy transportation and concentration, “it would be impossible to gather troops necessarily posted over a long line in sufficient strength, to oppose sudden movements. Wherever his fleet can be brought no opposition to his landing can be made except within range of our fixed batteries. We have nothing to oppose to its heavy guns, which sweep over the low banks of this country with irresistible force.”[1] He could not mount a cordon defense.

President Lincoln and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles had every intention of employing that sea power. However, in hindsight, their strategic vision was limited, and opportunities were lost for potentially decisive joint army/navy campaigns into the Southern heartland.[2]

A central component of Union strategy was to interdict trade with seceded states, starving them of funds, war materials, and necessities. On April 19, 1861, ten days after Fort Sumter, Lincoln issued a “Proclamation of Blockade Against Southern Ports.”

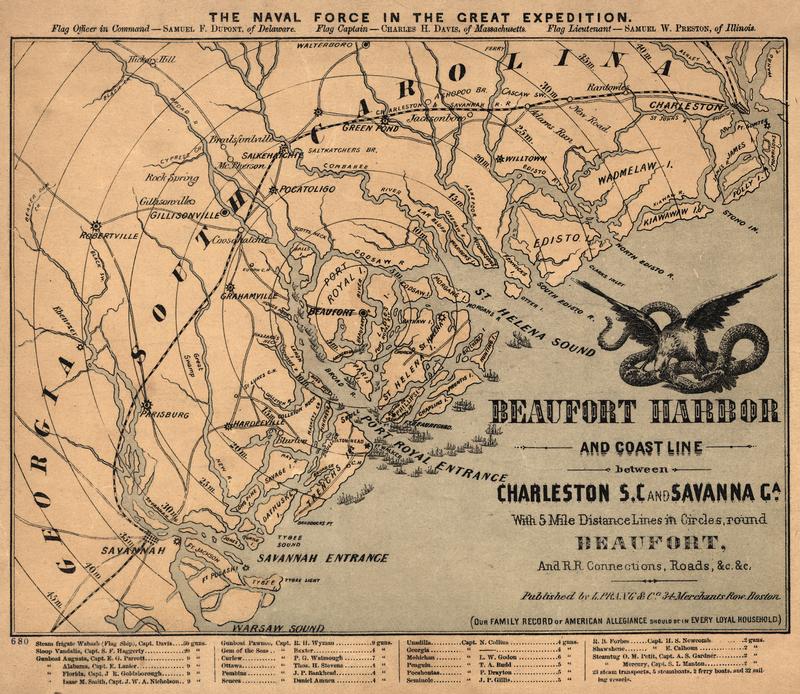

It was the most extensive naval blockade ever attempted, covering over 3,500 miles of low lying sand and swamp from Cape Hatteras to Matamoros. The blockade eventually would employ more than five hundred vessels manned by a hundred thousand sailors. But it required secure local bases from which to repair, resupply, and refuel blockaders, and to rest crews without long, wearying retreats to secure Norther harbors.

The Civil War demanded operations new to the U.S. Navy, employing innovative tactics and technology. These included: joint and amphibious operations; reduction of powerful shore fortifications; capture and control of heavily defended harbors, inland waterways, and contiguous coastal areas; interdiction of enemy trade, communications, and transportation—all while sustaining and protecting friendly forces. The navy, heretofore an exclusively deep-water force, had never thought very much about any of these power projection challenges.

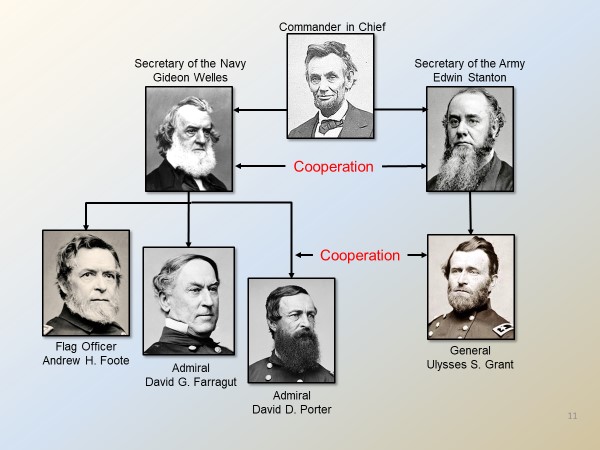

There were no protocols and no mechanisms for directing joint operations between land and sea services. The sole joint commander was the commander-in-chief; he was still learning the ropes in the winter of 1861-62. The command environment was muddled by George McClellan’s machinations to supersede Winfield Scott as commanding general. Army and navy secretaries managed separate fiefdoms. Officers of one service, however senior, could issue no orders to any officer of the other service, however junior.

Coordination depended entirely on the willingness and abilities of service secretaries to cooperate strategically, and of respective field commanders to mutually plan and execute operationally. Much depended on personalities. The Union was not ready to fully exploit weak Confederate coastal defenses.

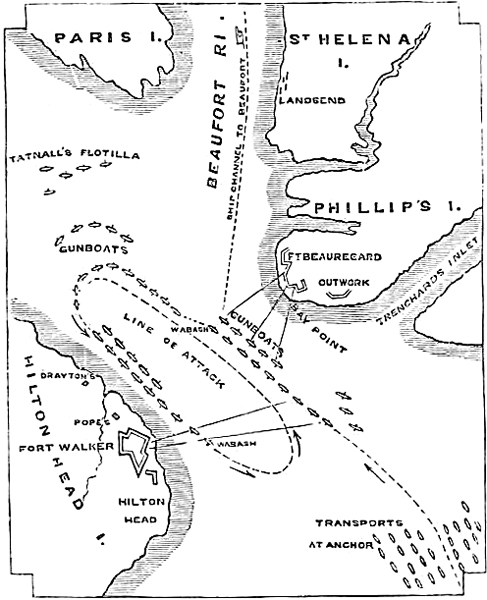

After months of discussion, Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, was selected as the target of an expeditionary force consisting of 17 warships and 60 transports under the command of Flag Officer Samuel F. DuPont ferrying 13,000 troops commanded by Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman (no relation to W. T. Sherman). Port Royal—one of the finest natural harbors on the east coast, situated inland from Hilton head between Savannah and Charleston—would be a wonderful base for blockading and for denying the Confederacy a major blockade-running port. Two major sand forts, Walker and Beauregard, with 3,000 Rebels and mounting about twenty guns each guarded the entrance.

Port Royal—one of the finest natural harbors on the east coast, situated inland from Hilton head between Savannah and Charleston—would be a wonderful base for blockading and for denying the Confederacy a major blockade-running port. Two major sand forts, Walker and Beauregard, with 3,000 Rebels and mounting about twenty guns each guarded the entrance.

The forts were incomplete and poorly designed; a shortage of heavy 10” Columbiads was partially offset by a larger number of smaller caliber guns. The fledgling Confederate Navy contributed one small converted coaster and three former tugs, each mounting two guns—the “mosquito fleet.”

DuPont and Sherman demonstrated excellent cooperation in planning and executing. As it turned out, however, Sherman’s troops were not needed; it was an all-navy show.

On November 7, 1861, DuPont steamed his squadron onto Port Royal in line ahead and ran a race-track course up and down the harbor blasting in succession the fort on one side and then on the other with all his broadsides.

On November 7, 1861, DuPont steamed his squadron onto Port Royal in line ahead and ran a race-track course up and down the harbor blasting in succession the fort on one side and then on the other with all his broadsides.

Some ships found they could stop and enfilade the water battery at Fort Walker in a position safe from return fire.

The mosquito fleet withdrew after lobbing a few shells toward the Yankees. Fort Walker defenders had difficulty hitting moving targets while losing their guns to enemy fire and running out of ammunition. They abandoned their positions.

Fearing isolation from retreat, those at Fort Beauregard followed. DuPont’s sailors rowed ashore, occupied the forts, and then turned them over to the army. Port Royal would be a Federal bastion for the remainder of the war.

“Both Sherman and Du Pont, to their credit, saw that Port Royal’s fall had potential that went far beyond serving as a logistical base for the navy’s blockading operations,” noted one historian.[3] A few months later Du Pont wrote that “the occupation of this wonderful sheet of water, with its tributary rivers, inlets, outlets, entrances and sounds, running in all directions, cutting off effectually all water communications between Savannah and Charleston, has been like driving a wedge into the flanks of the rebels between these two important cities.”[4]

The Confederate high command agreed, which is why President Davis dispatched Lee to take charge of coastal defenses. In the report cited above, Lee considered the aftermath of the Union victory at Port Royal: “I have thought [the enemy’s] purpose would be to seize upon the Charleston and Savannah Railroad near the head of Broad River [flowing into Port Royal Sound], sever the line of communication between those cities with one of his columns of land troops, and with his other two and his fleet by water envelop alternately each of those cities. This would be a difficult combination for us successfully to resist.”[5]

Lee improved fortifications and built up a defense in depth around Savannah with what forces he could muster. The Rebels blocked Federal land advances in the area for two and a half years. But the attention of Washington leaders was elsewhere; they did not try to exploit the potential for further joint operations at Port Royal.

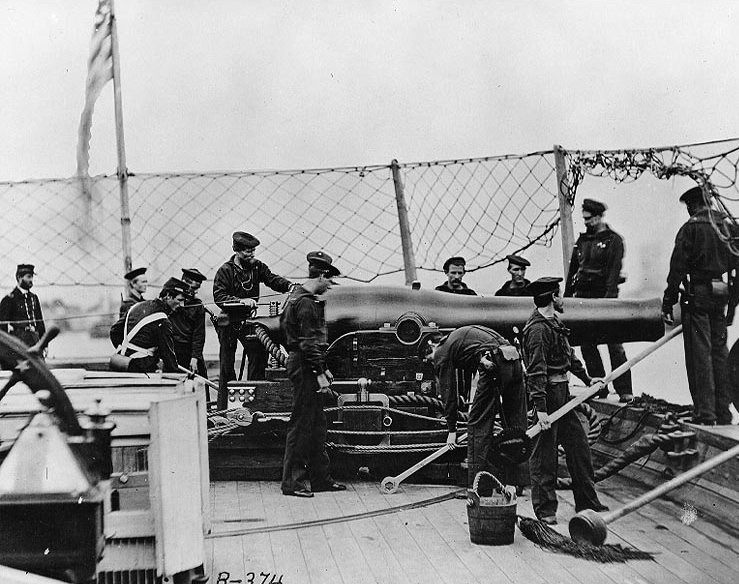

Two factors contributed to DuPont’s success there. The first was technology. For centuries, the sailing warship—subject to vagaries of wind—had little chance against shore batteries firing bigger guns from stable and usually higher platforms protected by stone ramparts and capable of employing heated shot.

But the navy had come a long way, demonstrating technical innovation and excellence in warship production. It was advancing rapidly in steam and propeller propulsion and was leading the ordnance revolution of the era. Larger steam men-of-war armed with heavier and longer range guns firing explosive shells were evening the odds.

Like DuPont at Port Royal, Admiral David G. Farragut would blow past powerful fortifications below New Orleans (April 1862) and again in Mobile Bay (August 1864) with greater but manageable casualties, isolating the forts into surrender.

Sea power did not always work alone, however. Farragut (in July 1862) and Admiral David D. Porter (in April 1863) could sneak their squadrons past massed batteries on Vicksburg heights with manageable damage but could not take the city on their own. Charleston Harbor became a cul-de-sac of fire and destruction for another Union squadron (April 1863)—including presumably impregnable ironclad monitors—defying all attempts at capture from the sea.

Given lack of institutionalized coordination and an incomplete appreciation of sea power or power projection, victory at Port Royal and elsewhere also depended on close and personal partnerships between senior commanders. U. S. Grant would agree that much of his success was due his relationships with salty compatriots like Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote (Forts Henry and Donelson, February 1862), Farragut and Porter.

From Grant’s first engagement at Belmont, MO (November 1861), through Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and finally on to Richmond, the navy provided heavy artillery support and pushed aside all Rebel water forces while transporting, supplying, and feeding Federal armies along all rivers and coasts.

Grant’s and Porter’s Vicksburg campaign culminating in its surrender on July 4, 1863, would become the most prominent example of joint operations. Under the leadership of Admiral Porter and Major General Alfred Terry, the bloody capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina (January 1865) was the ultimate Civil War amphibious operation.

Savannah and Charleston finally fell to the encircling hosts of General Sherman (December 1864, February 1865), but he rushed from Atlanta to Savannah for the express purpose of reestablishing logistic support from the sea and depended upon it from then on. What if these cities had been taken by joint operations in the spring of 1862?

[1] R. E. Lee to General S. Cooper, January 8, 1862, OR, Ser. 1, vol. 6, p. 367.

[2] Williamson Murray and Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh, A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War (Princeton & Oxford, 2016), Chapter 5, Stillborn between Earth and Water: The Unfulfilled Promise of Joint Operations.

[3] Murray and Wei-siang, A Savage War, 128.

[4] John D. Hayes, ed., Samuel Francis Du Pont: A Selection from His Civil War Letters, vol. 1, The Mission: 1860– 1862 (Ithaca, NY, 1969), p. 285.

[5] R. E. Lee to General S. Cooper, January 8, 1862, OR, Ser. 1, vol. 6, p. 367.

Excellent article of the land and sea operations of the war, covering topics not generally cover in most Civil War discussions. Thank you

Excellent graphics! Thanks.

Superb perspective. Because these operations are on a scale never seen before, as you rightly point out, there is a learning curve in terms of what is possible.

Reading dispatches and orders written by Sherman in 1861, it’s clear he was frustrated by the Navy’s lack of support for his land operations around Port Royal.. He assumed they are there to provide logistical support, not have their own priorities. That divide between services stalled the campaign for months.