“What Shall Be Done with the Slave?” The 9th Illinois Cavalry and Practical Emancipation

I am frequently sidetracked when scanning through historic newspapers on a quest for specific information. What can I say, the headlines are still doing their job. Such was the case while digitally flipping through August 1862 issues of the Chicago Tribune. “What shall be done with the slave?” asked the commander of the 9th Illinois Cavalry, stationed at the time near Helena, Arkansas. As I guessed, the officer had already reached an opinion of his own. His letter to the editor is a perfect summary of how many northern soldiers saw emancipation as a means to end the war, regardless of their stance on abolition before 1861.

Hiram Franklin Sickles was born in Otsego, New York in 1818. He attended the Philadelphia Naval Asylum and served in the navy for a decade, working in the Topographical Department and twice circumnavigating the world. Afterward he settled in Moline, Illinois where he operated a flour mill, occasionally practiced law, and dabbled in local politics.

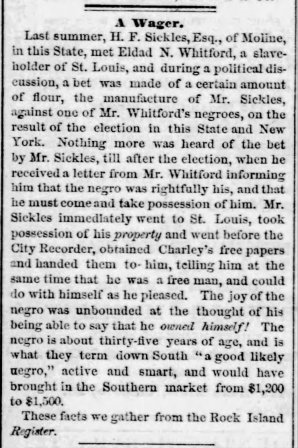

It appears that Sickles did already have anti-slavery sentiments before the war. A Chicago Tribune article from December 15, 1860 stated that he met a St. Louis slave owner while travelling for business during the summer. Their discussion eventually turned to politics, and, after disagreeing, the two placed a bet on the results of the upcoming election–Sickles wagered flour from his mill against one of Eldad N. Whitford’s slaves. Sickles won the bet but promptly freed the slave upon being summoned to St. Louis to take possession.

Sickles’s flour business along the Mississippi River caused him to spend considerable time in New Orleans. A possibly apocryphal story from his 1892 obituary stated that when Louisiana seceded the local authorities confiscated all of Sickles’s property, forcing him to return north “impoverished but full of patriotism.”

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles helped drill new volunteer soldiers. He received a commission as major in the 9th Illinois Cavalry in September 1861 and was promoted lieutenant colonel in February 1862, frequently commanding the regiment. Of personal interest, the 9th Illinois Cavalry contained several companies of soldiers from my hometown of Geneseo. The regiment operated in Arkansas during 1862 as part of Major General Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest.

Brigadier General Frederick Steele commanded one of Curtis’s division. He opposed confiscating slaves as “contraband of war” and reminded those around him of the orders of Major General Henry W. Halleck, commanding the department, “prohibiting fugitive slaves and unauthorized persons from coming within the lines.” The regimental historians of the 9th Illinois afterward noted that this directive showed “very clearly the delicate and kid-glove fashion in which at that time the war for the suppression of treason and rebellion was then being conducted.”

That approach began to change in late June when Curtis led an expedition through eastern Arkansas to reach the Mississippi River for resupply. The 9th Illinois participated in the march and suppressed an attack on the wagon train near Village Creek on June 27th. After suffering significant casualties, including the wounding of Colonel Albert G. Brackett, command passed to Sickles. The Army of the Southwest defeated another threat along their route at Cotton Plant on July 7th and safely reached the city of Helena one week later.

Their exposure to southern plantations along the way convinced them of the futility of waging a “soft war.” One member of the regiment, who called the march “one of the most arduous and fatiguing of any made during the civil war,” afterward recalled:

The weather was intensely hot, and the road lay through the malaria-breeding swamps and fenlands, where the trailing masses of Spanish moss on the great cypress trees wave like mourning bands over the reeking lands. Everything grows there in the rankest profusion, and the cotton and corn fields are most beautiful, the ground being rich and easily cultivated.

Most of the people residing in this region were strong in their secession feelings, and, being considerable slave-owners, were willing to shed their blood for what they considered right. There were many large plantations where great gangs of slaves were worked successfully, the cultivation being something marvelous.

A lawyer before the war, Curtis did not initially advocate for abolition. He continued to maintain that slaves of loyal citizens were not considered “contraband.” Such privilege did not extend to secessionists, however, and Confederate use of slaves to erect barricades along his route provided rationale to justify confiscation. The issue of emancipation was actively debated at the time in newspapers and in Congress but was not yet settled. Nevertheless, Curtis actively employed the contraband slaves his army encountered in foraging, scouting, guiding, and clearing the barricades along the route.

“Our Western boys were very thankful for their aid, and to it they attribute no inconsiderable share of the success which attended their march,” claimed the Chicago Tribune after an interview with Major William J. Wallis of the 9th Illinois Cavalry. “The Major further states that the prejudices which might have existed in the army against the employment of men of color in any way that they can be made useful, have entirely disappeared; and that soldiers who were the most rantankerous of Democrats when they started from home have become practical Abolitionists, to whom the work of liberation is now a positive delight.”

Of course there was no such unanimity in opinion. Captain Charles S. Cameron believed “a majority of the soldiers cared nothing about the question of slavery, but wished to fight the battles of the Country and let slavery take care of itself.” If Cameron’s statement was true, however, such sentiments were not publicly expressed to the same degree. Any such soldier opposition to emancipation put little damper on the desire of the slave population to seek freedom among the Union column.

Curtis commented to a correspondent with the New York Tribune about the intelligence and initiative of those who tagged along with his command, a testament to the grapevine communication network that undermined plantation owner efforts to keep their slaves ignorant. On July 31st the newspaperman wrote that the general remarked to him “that he was surprised at the intelligence they manifest and their perfect understanding of the causes of Rebellion and of their rights.” Curtis allowed those who came into Union lines at Helena to earn their own money through the sale of cotton seized from their former plantations.

Most estimates suggest that approximately 2,000 slaves reached Curtis’s army through the first week of August. That number steadily grew. For reference sake, the 1860 census listed a black population of 17,660 for the five counties through which Curtis’ expedition marched.

“The presence of the Army of the Southwest sounded the death knell of slavery in Arkansas’s premier agricultural region,” historians William Shea and Earl Hess recently concluded. “Curtis emancipated slaves on a mass scale, ignoring the fact that in mid-1862 he lacked the authority to do any such thing. In towns along the way soldiers commandeered printing presses and produced stacks of emancipation forms. News of what the Federals were doing spread like wildfire, and by the end of the campaign, more than three thousand refugee slaves, ‘freedom papers’ in hand, trailed the dusty blue column en route to an uncertain future.”

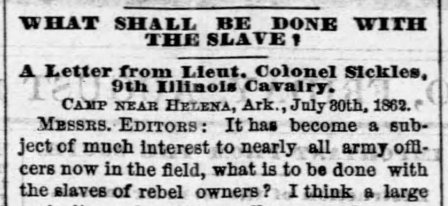

Lieutenant Colonel Sickles saw complete emancipation throughout the Confederacy as the best possible future. On July 30th he wrote a letter to the Chicago Tribune that appeared in print on August 15th.

It has become a subject of much interest to nearly all army officers in the field, what is to be done with the slaves of rebel owners? I think a large majority of both officers and men were, on entering the field, decidedly opposed to any policy, either civil or military, that would effect the “status” of the slave, in any of the States where the “institution” is legalized by proper local enactments. But a wonderful change has come over the entire surface of affairs, teaching us, through bitter experience that such doctrines are entirely incompatible with the successful prosecution of this war, on the part of the federal government or others in authority.

My own experience, as well as that of hundreds of other officers of the army of the Southwest, furnish to us the most unmistakable evidence that this rebellion cannot be conquered while this element of power is left to the disloyal slaveholder–and nearly all slave owners are disloyal. The sacredness which seems to surround this class of property in the South, gives to the enemy a tower of strength. We find that while the slave owners are in thousands of instances actually connected with the rebel army–guerrilla bands, or otherwise aiding and encouraging the common enemy of the United State government, the slave population is actively employed (under protection of our own troops) in carrying forward the different branches of material industry throughout the slaveholding States. Indeed, nearly all of the labor which gives to the south its important strength, is derived from this class of property, which seems to have had the benediction of all our prayers.

I have been taught, like many others, that where the slave has been unmolested in his labors, under direction of his owner or overseer, there we find nearly every white male inhabitant of suitable age absent from home, either in the rebel army or “bushwhacking.” Not only this, but the poor whites who are not able to own slaves, are furnished with labor to till their little patches of ground from the slave population, while they themselves are in the service of the enemies of our country.

In this way, our government is rending the most essential service to the South, in protecting and reserving a power to her, which she cannot find in any other direction. The negro is also employed in building fortifications for the enemy–constructing barricades and entrenchments, and in some instances have had arms put into their hands to use against our troops.

With these facts coming within the range of the knowledge and experience of nearly every officer in active service in the seceded States, I have no hesitation in saying, and of holding myself responsible for the truthfulness of the declaration, that, with all the energies at command of this government, this rebellion will likely to continue until either terms of peace are arranged between the contending parties, or that this important element of power, now reserved to the South by the military and civic authorities of the United States government, shall be weakened to such an extent that the slave shall no longer remain the bone and sinew, the entrenchment and stronghold of his rebellious master.

The changing attitude of the 9th Illinois Cavalry was but one of many similar experiences among Union forces throughout the south. President Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was only a month away.

Unfortunately, as is often the case in history, the story of the contrabands at Helena cannot be neatly wrapped up with that happy ending. Curtis left the Army of the Southwest in late August to take command of the Department of Missouri. General Steele therefore replaced him as army commander at Helena and soon reversed many of Curtis’s policies, particularly in regard to the slaves who thought they had found liberation within the Union army. Steele went so far as to actively encourage regional plantation owners to journey to Helena for the recovery of their slaves. By the formal signing of the Proclamation on January 1, 1862, however, Steele had moved on as well.

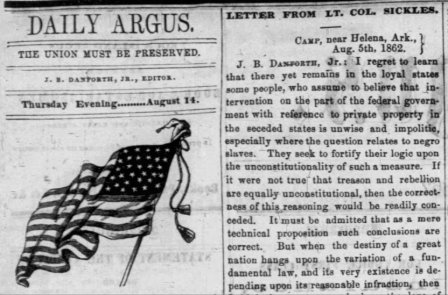

While researching Sickles, I found as a bonus another of his published letters. This one was addressed to the editor of a local paper, the Rock Island Argus and Daily Union.

Camp, near Helena, Ark., Aug. 5th, 1862.

J.B. Danforth, Jr.: I regret to learn that there yet remains in the loyal states some people, who assume to believe that intervention on the part of the federal government with reference to private property in the seceded states is unwise and impolitic, especially where the question relates to negro slaves. They seek to fortify their logic upon the unconstitutionality of such a measure. If it were not true that treason and rebellion are equally unconstitutional, then the correctness of this reasoning would be readily conceded.

It must admitted that as a mere technical proposition such conclusions are correct. But when the destiny of a great nation hangs upon the variation of a fundamental law, and its very existence is depending upon its reasonable infraction, then I think there are none who have the love of country in their hearts who will doubt the wisdom of such a measure. These nice distinctions, which gave to the politician the ground-work of his faith at a time when peace and prosperity were enjoyed by every citizen of this great commonwealth, can hardly hold their empire when the most crushing accumulation of disaster and ruin balancing in the scale, and ready to fall upon our unhappy country.

I know, from my own experience as a federal army officer, in active service in some of the seceded states, that the policy hitherto pursued and yet insisted upon by the tender footed demagogues, has placed in the hands of the enemy of our country a goodly portion of their material resources to prosecute this unholy war against us. As startling as this declaration may seem, it is nevertheless true, as I think I shall be able to prove.

Those who are familiar with the institutions of the south, and the organization of its society, will admit that the principal element of its material industry, consists in its slave population. This tower of strength still left to the undisturbed control of this refractory and rebellious people, and protected by the fostering care of our beneficial government, with all the omnipotent energies of its military and civic powers, how thankful ought these traitors to be that while they trample upon constitutions, and hurl defiance in our teeth, they still deal with a government that has such yearning solicitude and consideration for their wellfare.

The owners of negroes, in a majority of cases, so far as my observation extends, and I think it generally true, are directly or indirectly connected with the Confederate army in some way, either as officers, furnishers of supplies, or otherwise aiding and abetting this rebellion. The slave population is left at home, with the benediction of “political hacks” pronounced upon it, that this servile labor may continue to build fortifications and entrenchments for our enemies, construct barricades, and above all, to fill their grainaries from the abundant harvest,–the result of slave labor protected by us. There is but little cotton permitted to be raised in any of the slave states. This prohibition is by order of the rebel government. But all tillable land is to be employed in raising corn, wheat, oats, potatoes, and anything that will subsist its armies; and, again, the poorer class of white people who are not able to own slaves, are furnished by their more opulent neighbors with slaves to till their little patches of ground for the support of their families, while all the men of suitable age are fighting against us. These are facts, and I hold myself responsible for the truthfulness of the declaration.

You may as well undertake to reverse the current of the Mississippi with a clam shell as to bring this rebellion to a speedy and successful close, without humiliating compromises, unless we first cripple and weaken this great element of rebel power. At present I have no politics, and recite these facts for the benefit of my northern friends, who take a south-side view, only, of these questions.

Respectfully yours,

H.F. Sickles. Lt. Col. 9th Ill. Cavalry.

Sources:

“Moline Mills.” Moline Workman, November 4, 1856.

“A Wager.” Chicago Tribune, December 15, 1860.

“From Curtis’ Column.” Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1862.

Sickles, H.F. to “Messrs. Editors,” July 30, 1862. “What Shall Be Done With the Slave? A Letter from Lieut. Col. Sickles, 9th Illinois Cavalry.” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1862.

Guilbert to editor, July 31, 1862. “Interesting from Curtis’s Army.” New York Tribune, August 6, 1862.

Sickles, H.F. to J.B. Danforth, Jr., August 5, 1862. “Letter from Lt. Col. Sickles.” Rock Island Argus and Daily Union, August 14, 1862.

Browning, Orville H. Diary, October 14, 1862. Theodore C. Pease and James G. Randall, eds. The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Volume 1, 1850-1864. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Librabry, 1925.

“A Famous March: Fighting Our Way Through Arkansas.” Chicago Times, August 7, 1886.

Davenport, Edward A., ed. History of the Ninth Regiment Illinois Cavalry Volunteers. Chicago, IL: Donohue & Henneberry, 1888.

“Mustered Out.” National Tribune, July 21, 1892.

Hess, Earl J. “Confiscation and the Northern War Effort: The Army of the Southwest at Helena.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Volume 44, Number 1 (Spring, 1985).

Shea, William L. and Earl J. Hess. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Teters, Kristopher A. Practical Liberators: Union Officers in the Western Theater during the Civil War. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

An elegant and informative piece, good sir. Huzzah!

This is a very good post. It reflects the work of James McPherson in “For Cause and Comrades”, of Gallagher in “The Union War” and of Lamers in “The Edge of Glory”, a biography of William S. Rosecrans. All these works reflect the theme that the war was, at the first, a war to restore the union. As the current posting makes clear, and as the cited works reinforce, the abolition of slavery was a means to an end—weaken the Confederacy by enticing away a large portion of its work force—and thereby preserve the Union. It is noticeable in the post that slavery is viewed as an economic issue, not as a moral one. That most Americans shared this view at the time of the war has been forgotten.

This was a fascinating post. I have been learning about how the views of Union soldiers towards emancipation evolved over the course of the war, and how their attitudes towards slaves and runaway slaves matured as well. Your analysis and commentary, and the long excerpts from letters by Union soldiers, really enhanced my understanding. Your list of sources and the reading Michael Bradley added in his comment is appreciated.

To that, I’ll add a reading suggestion of my own: “When This Cruel War is Over: the Civil War letters of Charles Harvey Brewster” (Amherst MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992), edited with an introduction by David W. Blight. Brewster was from my neck of the woods, Northampton, Massachusetts. He enlisted as a private in the 10th Mass. Volunteers and rose through the ranks to lieutenant. His letters reveal a remarkable change in his attitudes towards slavery, emancipation and race over the course of the war, thanks to his contact with slaves and freed slaves while campaigning in the South. He certainly came to understand the economic and strategic logic of emancipating slaves and crippling the Confederacy, as did the Union officer you mentioned in your post. That practical argument took on a moral dimension later in the war, however, when Brewster began interacting with and working with African Americans as a recruiter and trainer for the United Colored Troops.