Artillery: Chickamauga – “The terrible roar of artillery . . .”

When one thinks of effective artillery use in a Civil War Battle, Chickamauga doesn’t leap immediately into the forefront. Certainly Gettysburg or Malvern Hill take those honors. Or Antietam, remembered by the Confederates as “Artillery Hell.”

But not Chickamauga – the quintessential soldiers’ battle. Fought in a heavily wooded locale, with just a few farm clearings hacked out of the recent wilderness, Chickamauga offered very few opportunities for artillery. Certainly, Union Brigadier General Thomas Wood agreed, declining to bring his cannon forward into his main defensive line on the morning of September 20, fearing the guns would be overrun.

We can, however, distill lessons on effective Civil War artillery use from the field of Chickamauga; which, after all, is one of the reasons that park was created, “. . . for the purpose of preserving and suitably marking for historical and professional military study the fields of some of the most remarkable maneuvers and most brilliant fighting in the war of the rebellion.”

That same Sunday, September 20, Union corps commander George Thomas did incorporate his artillery into his main line. His position around Kelly Field was studded with cannon, well-sited, and they played a significant role in breaking up repeated Confederate attacks.

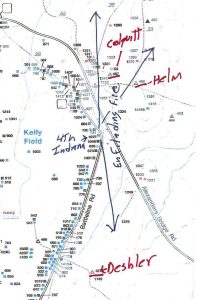

My favorite case in point is the position of the 4th Indiana Battery. Here, the Union line bulged eastward in a small salient, positioned atop a rise amid an open Cedar Glade, which provided the Hoosier gunners with excellent fields of fire to both their right and left. This allowed them to deliver enfilading fire against attacking Confederate infantry, with devastating results. Even though the 4th Indiana had suffered heavily in the fighting on September 19 and was now able to man only four of the battery’s six guns, those two sections played a major role in breaking up assaults delivered by at least three Confederate brigades. Rebel General Ben Hardin Helm and Col. Peyton H. Colquitt were both killed by shells from the 4th Indiana. Helm took a projectile in the bowels – probably a shell fragment, given where his marker sits today – and would die the next day. Colquitt was riding behind his brigade when, in the words of a South Carolina Sergeant, “a canister shot struck him in the breast and hurled him from his horse.”

The 4th Indiana’s fire also ranged south, reaching Brigadier General James Deshler’s brigade. Though other Federal guns played a role here, and likely the shell that tore through Deshler’s breast came from a different Union battery, flanking fire against Deshler’s Texans was in part the 4th Indiana’s doing.

Eventually, a Confederate attack in this sector did succeed, but only late in the day, and with considerable help. Some of that help provides us with a second example of effective artillery tactics: practiced by Rebel Captain Henry Semple, commanding Patrick Cleburne’s divisional artillery that Sunday.

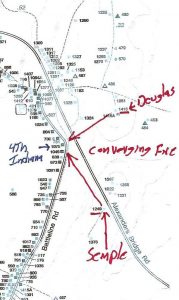

Semple understood the problem posed by the Indianans and understood how to counter it. The most effective way to use artillery in counter-battery fire is with converging fire: when two or more batteries combine to lay a crossfire on the target. At 4:00 p.m. on September 20, Semple did just that.

He posted Captain James P. Douglas’s Texas Battery east of and slightly north of the 4th Indiana Salient. He posted his own Alabama Battery, now under command of Lieutenant Robert Goldthwaite, about 400 yards to the south. Douglas’s guns were about 300 yards from the Federal line. His cannon included two six-pound smoothbores and two twelve-pound howitzers, both outmoded by the 1860s, but still effective at this range. Goldthwaite manned four twelve-pound Napoleons. When all eight Confederate pieces opened on the Indianans, they delivered an almost perfect ninety-degree intersecting crossfire – scientific gunnery at its finest.

The results were devastating. Rebel fire disabled a gun and exploded a limber in short order, which, confessed a corporal in the 4th, “sowed consternation in our ranks.” To Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Griffin of the 38th Indiana, stationed nearby, it seemed as if the Rebel artillery “hurled the grape around us in showers.” Two more guns had their axles damaged, rendering them unserviceable. Unable to bring up more ammunition, the 4th Indiana retreated, having suffered twenty casualties over the course of the battle. The position was overrun by Confederate infantry, who also took prisoners from Union Brigadier General Absalom Baird’s division. Semple’s use of artillery could be a textbook example of effective artillery preparation in the attack.

Thus, while Chickamauga may not conjure up images of immense artillery bombardments or grand barrages, it does still impart useful instruction in the methods by which Civil War gunners fought. Almost every time I visit the park, I try and take a minute to stop at the 4th Indiana position and remember what happened there on Sunday September 20, 1863.

Superb article. I am among the many who saw the Chickamauga battlefield as a place that batteries entered only to be overrun. Glad to see effective use of anti-personnel and counterbattery fire illustrated from both sides.

This is a great article. There is so much to learn about this battle.

Superb material..

I really enjoyed the unique maps you put on this post. Thanks for sharing!