Private Luke Quinn – The Unlikely Celebrity of Harpers Ferry

Emerging Civil War welcomes back Jon-Erik M. Gilot

When Private Luke Quinn arrived in Harpers Ferry, Virginia on October 18, 1859 he likely did not imagine that he’d never leave. He certainly could not have imagined that he’d be popularized in the small town with a namesake pub, an interesting monument and an unrestful sleep in St. Peter’s Cemetery. Here’s a quick look at the lively afterlife of the most unlikely celebrity of John Brown’s Raid…

Little is known about Private Luke Quinn prior to his untimely death. From his military records we know that he was born in Ireland in 1835 and arrived in the United States with his parents in 1844. He worked as a common laborer until November 1855 when he enlisted for a term of four years as a private in the United States Marine Corps at Brooklyn, New York. He would train at the Marine Barracks in Washington, DC until September, 1856 when he was assigned to the frigate USS St. Lawrence. He served aboard the St. Lawrence and the USS Perry on expeditions to Brazil and Paraguay and arrived back at the DC barracks in May 1859, his term of enlistment nearing its end.

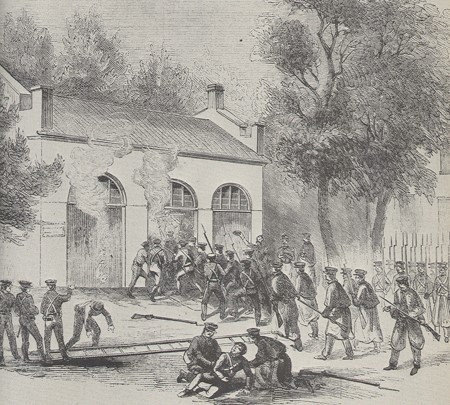

On October 17, 1859 Quinn was among the approximately 100 Marines dispatched to Harpers Ferry by President James Buchanan to quell a rumored insurrection at that place. The Marines arrived at the United States Armory at Harpers Ferry the following morning to find a band of raiders under the command of Captain John Brown of Bleeding Kansas fame. Brown and his men had arrived at the Ferry to seize a cache of weapons stored at the arsenal there and to liberate slaves from local slaveholders. Local militia companies, railroad workers and armory employees had cornered the raiders and their civilian hostages inside the armory engine house. After a final, unsuccessful attempt to engage Brown and negotiate a surrender, Colonel Robert E. Lee commanded the Marines to attack the engine house and quell the insurrectionists.

(Harper’s Weekly)

A group of Marines stormed the engine house, battering the heavy door with sledgehammers. Lieutenant Israel Green – tasked with leading the assault – espied a nearby ladder and ordered the Marines to use it as a battering ram. After a few blows the lower section of the door collapsed and Green gained entry into the dark, hazy engine house. Immediately behind Green entered Private Quinn. As Green recalled in 1885,

“The Marine who followed me into the aperture made by the ladder received a bullet in the abdomen, from which he died in a few minutes.”

Green couldn’t be certain but he believed it was John Brown who fired the fatal shot. Hostage John Allstadt likewise believed Brown to have fired the shot that killed Quinn. In testimony during the trial that followed the raid, Allstadt stated that…

“He [Brown] fired at the marines, and my opinion is that he killed that marine.”

On cross-examination Allstadt clarified that he could not definitively say it was Brown that fired the fatal shot, and that he [Quinn] “might have been killed by shots fired before the door was broken open.”

Private Quinn was one of two Marines injured during the assault on the engine house and was the only Marine fatality. He had less than five weeks left on his term of enlistment. In a letter written just three months following the raid, Father Michael A. Costello, pastor of St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Harpers Ferry, recalled the events…

“In the final attack on the insurgents two of the soldiers were wounded, one of them mortally. As both were Catholics I was summoned to attend them. As Private Luke Quin[n] fell, pierced through with a ball, his first exclamation was to Major Russel[l], of the United States Marines, who seeing him fall, went up to him. In pitiful accents he cried out “Oh! Major, I am gone, for the love of God will you send for the priest.” I administered to him the holy rites of the Church; he died that day, and was buried with military honours in the Catholic graveyard at this place.”

David Hunter Strother likewise recounted seeing the mortally wounded Quinn…

“As I passed the window at the Old Superintendent’s House, now used as an office, an acquaintance beckoned me to enter. I did so, and found there lying on the floor a marine who was mortally wounded. He was an Irishman named Quinn, a mere boy & his sufferings must have been great as his cries and screams made one’s flesh creep. A priest knelt beside him and like the friar in Marmion – “With unavailing cares, exhausted all the churches prayers” to soothe the dying soldier’s agony.”

Quinn’s remains were interred in an unmarked grave in St. Peter’s Cemetery in Harpers Ferry where they would remain for 68 years. In 1927 local physician Walter Dittmeyer, resident Loughlin Mater and Reverend John Curran undertook an effort to locate Quinn’s grave and provide a proper marker. The trio also enlisted longtime resident Thomas Boerley, whose father had been killed by one of Brown’s men during the raid. They identified the spot that oral tradition held as Quinn’s burial location and soon disinterred a partial skeleton, including a skull and fragments of the long bones. Brass buttons, bits of a greenish-blue uniform and a Catholic emblem gave the group reasonable certainty that they’d located Quinn’s grave. Pieces of the uniform were acquired by West Virginia historian and John Brown buff Boyd Stutler, who displayed the morbid artifacts at West Virginia University in 1955.

(findagrave.com)

In 1931, the Holy Name Society of the Diocese of Richmond passed a resolution to erect a monument on Quinn’s grave. It took nearly a decade before the monument was dedicated on May 5, 1940, where it stands to this day. In 2012 a local Marine Corps League detachment rededicated the gravesite and installed a new marker and flagpole.

(findagrave.com)

But Private Quinn’s story doesn’t end there…

In 2009 a pub and eatery opened in a ca. 1830’s building along Potomac Street in Harpers Ferry with Private Quinn – who had died less than 500 feet away – as its namesake. Private Quinn’s Pub was a popular stop for hikers, tourists and residents until the devastating 2015 fire that swept the Harpers Ferry historic commercial district. The pub was heavily damaged during the fire and opted not to reopen – the restored building today houses Almost Heaven Pub and Grill.

In 2009 a pub and eatery opened in a ca. 1830’s building along Potomac Street in Harpers Ferry with Private Quinn – who had died less than 500 feet away – as its namesake. Private Quinn’s Pub was a popular stop for hikers, tourists and residents until the devastating 2015 fire that swept the Harpers Ferry historic commercial district. The pub was heavily damaged during the fire and opted not to reopen – the restored building today houses Almost Heaven Pub and Grill.

For nearly a century Harper’s Ferry has worked – sometimes unconventionally – to keep alive the memory of Private Luke Quinn, an otherwise faceless soldier who was among the first of hundreds of thousands to follow in the years ahead.

(findagrave.com)

Jon-Erik M. Gilot holds degrees from Bethany College and Kent State University. He has been involved in the fields of archives and preservation for more than a decade and today works as an archivist in Wheeling, West Virginia.

An interesting bit of history. Thanks for sharing it. Rest in peace, Pvt. Quinn.

As an Irish native now residing in Harpers Ferry i have taking to visiting PVt Quinn’s grave and along with a young Marine captain of Irish decent we have left an Irish cross and flowers on the grave. May he rest in eternal peace now and his service and his memory live on forever.

interesting he could have been one of my ancestors

As a Marine 1990-1994 i ask that anyone visiting PVT Quinns grave on every Nov 10 to leave a slice of Birthday cake on his grave, as to conform to Marine Corp Tradition. Every Marine gets cake on the Marine Corp Birthday. RIP Semper Fi Pvt Quinn!

The granite bench and flagpole was installed near his grave years ago as a Eagle Scout project by a young gentleman by the name of Van Applegate who resides in Charlestown wv