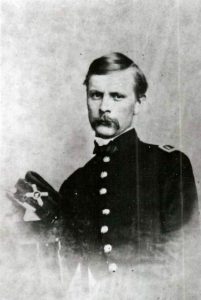

Artillery: Sticking to his guns – Lt. Charles Parsons at the Battle of Perryville

Napoleon Bonaparte himself once said, “It is with artillery that war is made.” So too could it then be said that it is with artillery that war is lost.

Napoleon Bonaparte himself once said, “It is with artillery that war is made.” So too could it then be said that it is with artillery that war is lost.

Such was the case atop a ridge outside of Perryville, Kentucky on October 8, 1862. The ridge today bears the name incredibly not of the highest ranking officer killed there during the Battle of Perryville, but instead that of a lieutenant who literally stuck to his guns to the very end before abandoning them on the field: Lt. Charles Carroll Parsons.

Parsons’ early life hardened him for the trials to come. His father died shortly after Charles’ birth in Ohio in 1838. He grew up with his uncle and showed a penchant for doing well in school. That ability earned him a spot at the United States Military Academy, which he entered in 1857.

Parsons made many friends at West Point. His classmates recalled his kind nature and his willingness to help out his fellow West Pointers, even “if it was spiced with self-sacrifice.” Doing so “seemed to give not pleasure only, but a visible joy.” Despite his glowing and affable personality, Charles Parsons had a rugged side. During his cadet years, he took on a man with a much larger stature than he in a fight. Parsons’ opponent knocked him to the ground seven times, but each time Charles stood back up “without ever a thought of quitting so long as he could get up.” Charles Carroll Parsons graduated 13th in the June 1861 class, one spot behind Alonzo Cushing.

Lieutenant Parsons bounced around from post to post in the war’s early years west of the Appalachians. At Louisville, Kentucky in September 1862, Parsons received the opportunity to lead a battery of guns into action, though the circumstances were likely less than ideal for the recent graduate.

Federal forces huddled in Louisville during the summer of 1862 in an attempt to prevent Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi from making its way north of the Ohio River. Panic seized the United States. “The situation at Louisville in the latter part of September, 1862, was not unlike that at Washington after the first battle of Bull Run,” remembered one Federal staff officer.

During the chaos, recently promoted brigadier general and infantry brigade commander William Terrill pulled guns and volunteers together to create a super battery of sorts to attach to his brigade. Terrill himself was a former artillerist and took an intense interest in the battery’s formation and subsequent actions. All told the battery that fell under Lt. Parsons’ command consisted of five Napoleons, two howitzers, and one 10 lb. Parrott rifle. Skilled artillerists were few and far between to fill a battery of eight guns, so Terrill took volunteers from his infantry regiments to stock his mutt battery. Together, 136 volunteers made up Parsons’ Battery, though most of the volunteers had hardly been in the army before their assignment to this motley assortment of guns. One Army of the Ohio officer said the battery “was not regularly organized.” It was hardly an ideal assignment for Lt. Parsons.

Major General Don Carlos Buell began moving his reinvigorated Army of the Ohio out of Louisville on October 1, 1862. Buell planned to cut Bragg off from his escape route back into Tennessee. As the army marched forward, Parsons’ cannoneers only had a couple of weeks of training with their field pieces. The two armies came to grips on October 8, 1862 outside of Perryville, Kentucky.

During the afternoon of October 8, as Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s 1st Corps deployed northwest of Perryville, McCook ordered William Terrill’s untried brigade to occupy a bald hill overlooking the Chaplin River in order to secure much sought after water in those dry October days. Lt. Parsons’ battery wheeled into position atop the hill alongside the 123rd Illinois Infantry and began pounding away at the first Confederate attackers of the day led by Brig. Gen. Daniel Donelson. One eyewitness saw Parsons leading his guns into position: “The fire of battle was in his eye and one guessed that the trot the bugle sounded was less because of any emergency in the order he had received than of his own impatience for the fray.”

While Parsons’ guns faced south to hit Donelson’s men, a Tennessee and Georgia brigade under Brig. Gen. George Maney appeared at the base of the hill where Parsons deployed his guns a mere 200 yards away. The lieutenant quickly swung his guns to face this new threat coming from the east.

Maney’s Southerners found a fence at the base of the hill from which to find cover and fire upon the Federals staring down at them. Here William Terrill jumped in amongst Parson’s guns. During the fight, according to a member of the 105th Ohio Infantry, the actions of Terrill’s pet project “eclipsed in interest the maneuvering of his brigade.” To save Parsons’ Battery and keep Maney’s men at a respectable distance away from the guns, Terrill ordered the 123rd Illinois to fix bayonets and dislodge the Confederates beneath him. The green Illinoisans departed on this hefty mission but just as quickly came streaming back up the hill; one-fourth of the regiment fell in the attack. “The fear of losing his battery evidently blinded General Terrill to all other considerations,” one member of his brigade mused.

During the firefight, Federal division commander Brig. Gen. James Jackson fell standing near Parsons’ line. Maney’s men were pouring just as much fire into Parsons’ cannoneers and Terrill’s infantry but the situation at the base of the hill 120 yards away was quickly falling apart for the Confederates. “It seemed impossible for humanity to go farther, such was the havoc and destruction that had taken place in their ranks,” wrote a soldier in the 6th Tennessee Infantry. Lieutenant William Turner’s Mississippi Battery dropped trail behind Maney’s infantry and added their metal to the fight. George Maney recognized that retreat here was not an option. “Go,” he ordered a staff officer, “direct the men to go forward, if possible.”

Parsons’ gunners and their infantry support continued to keep it hot for Maney’s Confederates as they moved uphill, stalling the attack short of the goal. “[T]o hold the field the capture [of] [Parsons’] battery was a necessity,” Maney related and he put the full force of his brigade into the charge. This final push was enough to force the Federals off the hilltop, driving them to the rear in confusion.

With the Federal left flank breaking, thanks in part to Terrill’s focus on Parsons’ guns according to one soldier, Lt. Charles Parsons relied on his tenacity to attempt to resurrect the worsening situation. With his volunteer artillerymen falling back around him, Parsons stood to his guns. “He remained with [his battery] until deserted by every man around him,” commented Maj. Gen. McCook in his report of the battle. Ultimately, Parsons “had to be removed by force” from his guns and moved to the rear away from the victorious Tennesseans now in possession of seven of the battery’s eight guns.

As Parsons headed for the rear, he “appeared perfectly unmanned and broken-hearted.” He told Capt. Percival Oldershaw, “I could not help it, captain; it was not my fault.” Charles Parsons did put up a heroic fight on top of the ridge at the Perryville battlefield that bears his name. His untrained artillerymen paid dearly for their stand, losing 10 men killed, 19 wounded, and 10 missing or captured, roughly 29% of the battery’s strength. Approximately fifty of the battery’s horses were shot down, as well, and the battery was disbanded in Perryville’s aftermath.

Veterans of the battle wondered what the outcome might have been on the Federal left had William Terrill, who later died during the fight, acted more the part of a brigade commander than a battery commander. Terrill sought to make his battle with his artillery and he ultimately lost that gamble and imperiled Buell’s left flank.

Charles Parsons received praise for his heroics on October 8, 1862. He received a brevet promotion to captain as a result and received another brevet for a solid performance at the Battle of Stones River a couple of months later. Parsons served the United States for the rest of the war and resigned from the army in 1870. He became an Episcopalian minister in Memphis and died in 1878 while heroically serving victims of a yellow fever outbreak. Charles Carroll Parsons stood to his guns to the very end.

We stood on Parson’s Ridge recently while touring Perryville. It was one heck of a fight on that part of the battlefield. Ole Sam Watkins of Company H agrees with me 🙂

I reckon we will tour that field again when the ABT gathers for the Annual Conference in May of 2019 in Lexington, KY. ‘Til the battle is won.

Parsons was also connected to three other famous Civil War personalities. He was a close friend to his West Point classmate, George A. Custer, and he studied theology with Chaplain, Doctor and later Bishop Charles Todd Quintard in Memphis, having been inspired by a sermon Quintard gave in New York while Parsons was a teacher at West Point. When ordained, he was the rector of a church in Memphis attended by Jefferson Davis. He is buried in Memphis’s Elmwood Cemetery, among other victims of the 1878 epidemic.

Sam,

Bishop Charles Quintard was also at Perryville as a Confederate Chaplain. He wrote a fanciful account of his observations of Parson’s Battery and of Parson’s individual bravery. Quintard wrote:

“The Federal Battery was commanded by Col. (sic) Charles C. Parsons and the Confederate battery by Captain William W. Carnes. (Carnes was a graduate of the US Naval Academy). …I took a position on an eminence at no great distance commanding a view of the engagement and there I watched as Capt. Carnes managed his battery with the greatest skill killing and wounding nearly all of the officers, men and horses of Col. (sic) Parson’s battery. Col. Parsons fought with great bravery and coolness fighting and serving a single gun as the Confederate infantry advanced. A Confederate officer ordered his men “shoot him down!” As the guns were being leveled, Col. Parsons drew his sword and stood at ‘Parade Rest’ to await his fate. The Confederate Colonel was so moved by the bravery and calmness that he commanded his men to lower their guns “No, you cannot shoot such a brave man!” and Colonel Parsons was allowed to walk off the field. Subsequently I captured Colonel Parsons for the ministry pf the Church in the Diocese of Tennessee.”

Kevin – Parsons was quite a remarkable man, thank you for the article.

As an FYI, another famous graduate of the Class of 1861, Henry Du Pont, stood up for Parsons at his June 13, 1862 wedding to Celia Lippett , of Brooklyn, NY.

Victor, thanks. I was indeed aware of that:

https://lsupress.org/books/detail/doctor-quintard-chaplain-c-s-a-and-second-bishop-of-tennessee/

Thanks to both of you for adding more to Parsons’s incredible story!

Kevin: Thanks for this excellent article. That ad hoc “battery” would have driven Henry J. Hunt nuts. The mix of ordnance and ranges alone violated all of his preferences.

Thanks, John. I think you’re right about Hunt. He would not have liked that one bit.

Nice article. Parsons’ Ridge (you might also see it called the Open Knob) is one of the great views at Perryville.

Kevin, Great article and invokes a personal response inspired by your “not regularly organized” description and mention of the 105th Ohio Volunteer Infantry that also came to the Perryville fields woefully trained. My great uncle Eben(eezer) Fishel was a member of that regiment and was captured during the battle and exchanged on the 9th afterwards. Watkins description of that battle is horrific and it’s hard to imagine an untested infantryman being in any way prepared to deal with it effectively. Eben’s dismally brief regimental report simply describes him as dying of “disease” in May of ’63. His father and two younger brothers (the youngest being my great-grandfather Warren) all served in the Union Army and survived, but not without bearing wounds from their service.

My GGGgrandfather was in the 80th Illinois, next to your uncle.

Great post Kevin

There is little enough said about junior officers in the regular artillery and much less on the relatively small number serving in the Army of the Cumberland. J

Thanks, Jim! I agree with you. Maybe your second study? 😉

My great-grandfather was named Charles Parsons. Could he be named after this soldier? Anyone have his family tree?

John, email me at parsons_james@att.net and provide any family info you may have that would help ID Charles Parsons. I belong to the Parsons Family Association and have a few ways to track members of our tree. Cheers, James Parsons

My Great Great Great Grandfather was John Cornelius Curtright. He was Captain of Company E, 41st GA Infantry, “Troup Light Guard.” The 41st GA was part of Maney’s Brigade that day, positioned just to the left of Sam Watkins’ 1st TN Infantry. As the battle began at the base of that hill on which Parsons’ battery stood, my ancestor exhorted his men to “Keep cool, boys. Shoot low.” He was soon after shot in the abdomen, the ball exiting his lower back. His manservant carried him from the field, and then to Harrodsburg after the Confederates withdrew there. He died the next morning in a “Widow lady’s house” and was buried in the Strangers’ Cemetery there. He was 32 years old, and was survived by his wife and two young children. I have been to that battlefield several times.