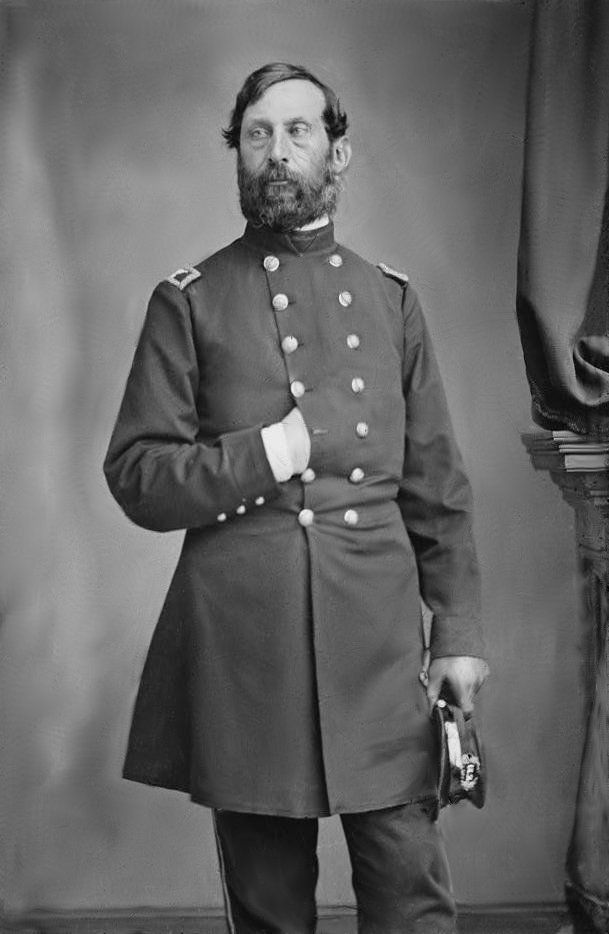

Artillery: Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery for the Army of the Potomac

From Little Round Top, Henry J. Hunt – Chief of Artillery for the Army of the Potomac – observed the opening shots of the Confederate artillery barrage near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 3, 1863. From his vantage point gained during an inspection of the Union lines, this artillery officer peered out into the distance, spotting the Rebel “batteries already in line or going into position”[i] along a line which stretched from the Peach Orchard to the edge of town to the north.

From Little Round Top, Henry J. Hunt – Chief of Artillery for the Army of the Potomac – observed the opening shots of the Confederate artillery barrage near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 3, 1863. From his vantage point gained during an inspection of the Union lines, this artillery officer peered out into the distance, spotting the Rebel “batteries already in line or going into position”[i] along a line which stretched from the Peach Orchard to the edge of town to the north.

Earlier in the day, General Hunt had ordered his artillery units to wait for the Confederate’s next move, then fire strategically to knock out troublesome enemy batteries. Now, he began to revise his plans after observing hurried activity in the Confederate infantry lines before the opening shots. Convinced an infantry assault was coming somewhere along the Union line, Hunt rode back along the Union position, directing his battery commanders to reserve fire and avoid an artillery duel, which would simply exhaust the ammunition supply prior to the infantry’s appearance. Next, he ordered the last four batteries of the artillery reserve to start moving toward the Union battle line.

Though the storm of shot and shell, Hunt rode the cannon lines along Cemetery Ridge, keeping a close eye on his artillerymen and ordering them to cease firing as they used their ammunition too quickly. Sometime during those blasting hours, General Hunt and General Hancock, who commanded the Union II Corps, conflicted about the role of artillery at that moment. Hancock wanted the big guns firing to protect and hearten his men and used blistering language at Hunt’s artillery commanders who fired back verbally, saying they would obey their chief and conserve the ammunition.

Who was this Chief of Artillery, so often mentioned in Gettysburg books, but not often presented with biographical details? Henry Jackson Hunt’s “road to Gettysburg” had been a journey closely linked with artillery and a professional military career. During the Civil War, he organized artillery batteries, used wise tactics, and led with common sense on the battlefields.

Born on September 14, 1819, Hunt grew up in a family that prized military tradition, service, and honor. His grandfather, Captain Thomas Hunt, had commanded batteries in the Revolutionary War and his father, Lieutenant Samuel W. Hunt, served in the 3rd U.S. Infantry. Henry Jackson Hunter continued the family’s military service records, entering West Point in 1835 and graduating four years later, nineteenth in a class of thirty-one.

As a second lieutenant, Hunt served in the 2nd U.S. Artillery, moving between outposts and forts along the Canadian border, eastern post, and New York Harbor defenses. He made first lieutenant on June 18, 1846, just after the Mexican American War began. In that conflict, Hunt was a junior officer with Duncan’s Light Battery and saw action at the Siege of Vera Cruz, Battles of Cerro Gordo, Cherubusco, Molino del Rey, Chapultepec, San Cosme, and the Capture of Mexico City. Twice wounded and twice brevetted, he ended the war as a brevet major who had attracted the attention of commanding officers for his artillery skills. General Worth wrote, “Finally, at five o’clock, both columns had reached their positions, and it then became necessary, at all hazards to advance a piece of artillery to the evacuated battery of the enemy, intermediate between us and the Garita (San Cosme). Lieut. Hunt was ordered to execute this duty, which he did in the highest possible style of gallantry, equally sustained by his veteran troops, with the loss of one killed and four wounded out of nine mine, although the piece moved at full speed over a distance of only one hundred fifty yards; reaching the breastwork he became muzzle to muzzle with the enemy. It has never been my fortune to witness a more brilliant exhibition of courage and conduct.”[ii]

Returning east, Hunt met, courted, and married Emily Caroline DeRussy Hunt; the wedding took place on December 18, 1851, at Fortress Monroe.[iii] Their first daughter arrived in 1852 and a son was born in 1855. The young officer’s life seemed balanced and a promotion to Captain of the 2nd Artillery in 1852 secured him a good position. However, Emily never recovered from complications of her son’s birth and died in 1857. Though his wife’s death was not unexpected, Hunt “was unprepared to accept the anguished realization that her loss had cast him and his motherless children adrift.”[iv]

Captain Hunt headed west, trying to suppress his grief with frontier service for the Utah Expedition (1858) and at Fort Brown, Texas. During this period, he also served as a member of the board which revised light artillery tactics and produced a report eventually published by the War Department as an artillery manual. Returning east, Hunt remarried, finding a kind step-mother for his children. Mary Bethune Craig Hunt[v] had two children, Conway (b. 1861) and John Elliot (b. 1874).

During the winter of 1860-61, Captain Hunt was asked to command the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, a strategic location eyed by Rebels. He also received another important assignment, a secret mission to secure Fort Pickens for the Union in April 1861. Hunt returned to his regular army battery, joining up with them at New York City on July 13 and shipping out to Washington the following day; by the 19th, the battery arrived with the rest of the “green” Union army heading to the fight near Manassas. During the fight, Hunt commanded Company M of the 2nd U.S. Artillery, and at one point, ordered his artillery to reload and fire on quickly advancing enemy soldiers, without pausing to sponge the cannons (a dangerous decision). However, no disasters occurred, and in the Union retreat from the battlefield, Hunt calmly withdrew his cannons from the fight and then helped other officers halt the collapse of the Union’s left wing, winning praise from General Winfield Scott.

Promoted to Major of the 5th Artillery and recognized by the president for the artillery manual, Hunt was appointed Chief of Artillery to oversee Washington City’s defenses to the south of the Potomac River. George McClellan – impressed with Hunt’s skill set – gave him the task of organizing the Army of the Potomac’s artillery reserve and made sure he received a regular army colonel’s commission in September 1861. In addition to his duties, Hunt spent the winter serving as President of the Board to Test Rifled Guns and Projectiles and an active member of the Board for the Armament of Sea-coast Fortifications.

When spring came, McClellan took the new Army of the Potomac to the Virginia Peninsula, and Colonel Hunt went along, commanding the artillery reserve. He was present and overseeing his field guns at Yorktown, Gaines Mill, Garnett’s Farm, Turkey Bend, and Malvern Hill. When General Barry resigned, Hunt received appointment to command all the artillery for the Army of the Potomac in September, a position he held through the end of the conflict; he also received promotion to Brigadier General of Volunteers. General McClellan praised the new Chief of Artillery, saying, “The services of this distinguished officer in reorganizing and refitting the batteries prior to and after the battle of Antietam, and his gallant and skilful[sp] conduct on that field, merit the highest encomiums in my power to bestow.”[vi]

At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Hunt directed the artillery barrage on the town and in the later weeks watched his guns get stuck during Burnside’s Mud March. General Hooker limited Hunt’s duties and role, leading to difficulties with the Union artillery at the Battle of Chancellorsville until the Chief received orders to do whatever was necessary to correct the issues.

Then, on the fields at Gettysburg, Hunt’s artillery knowledge, determination, and cautious tactics ensured the Union line’s cannons still had ammunition to fire when the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge began on that afternoon of July 3, 1863. Trusted by Meade and forceful enough to inspire his artillerymen to obey his orders rather than the irate Hancock’s, the Union Chief of Artillery played a crucial role in the Union success on Cemetery Ridge.

As the barrage continued, Hunt gave orders which – unknowingly – deceived the Confederates; he directed several batteries to withdraw near the center of the line, causing the Confederates to think the batteries were destroyed. However, Hunt replaced the withdrawn batteries with artillerymen and cannons from the reserve, making sure the artillery line stayed strong along the ridge.[vii]

Hunt watched the gray-clad infantry begin their advance from Freeman McGilvery’s battery position, seeing the destruction caused by the ammunition he had insisted to conserve. Later, when the Confederate infantry broke the Union lines at The Angle and reinforcements rushed forward, Hunt rode directly into the fray, firing away with a pistol at the advancing Rebels until his horse was shot, pinning him to the ground. Some nearby cannoneers rushed to help him, and General Hunt finished that battle day with no serious injuries.[viii]

“For gallant and meritorious services at the battle of Gettysburg,”[ix] Hunt received a promotion to Brevet Col. U.S. Army and the following year another promotion to Brevet Major General of Volunteers. Henry J. Hunt continued his duties as Chief of Artillery for the rest of the war, fighting in the Mine Run and Overland Campaigns. He became an adviser to General Grant who recognized Hunt’s abilities in special orders on June 27, 1864: “In all siege operations about Petersburg, south of the Appomattox, Brig. General H.J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery of the Army of the Potomac, will have general charge and be obeyed and respected accordingly. Col. H.L. Abbot, in charge of the siege trains, will report to Gen. Hunt for orders.”[x]

At the end of the Civil War, despite the brevets and rank commanding volunteers, Hunt remained a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army. He served in the west, in Reconstruction districts, as President of the Permanent Artillery Board, and as a member of the Board for the Armament of Fortification, continuing to command and influence artillery units. After forty-four years of active military service, Hunt retired on September 14, 1883. In the later years of his life, he moved to Washington and held the position of Governor of the Soldiers’ Home, which had been established for Union veterans. The life-long artilleryman died on February 11, 1889.

In post-war years, George McClellan praised Henry J. Hunt with these words:

“The command he thus exercised was quite equal in importance to that of an army corps, and frequently called for more hard work and far greater administrative ability. His work was not confined to administrative duties, but on every battlefield of any importance he displayed not only the…gallantry of the soldier but the highest military qualities of a general of artillery. My opinion was that he was as good a Chief of Artillery as it was possible to have, and I doubt whether he had his superior in the field in any European army.”[xi]

During the Civil War, Henry Hunt’s artillery knowledge and skill made major impact on many battlefields – Malvern Hill, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Petersburg, just to name a few. Often overlooked or just briefly mentioned in many military studies, Hunt fought to save the Union and his efforts ensured the success of Union artillery positions and effectiveness on battlefields. In that afternoon barrage at Gettysburg, the image of General Hunt, riding the lines and admonishing his cannoneers to hold fire, gives a glimpse into the leadership, courage, and wisdom so often displayed by the Army of the Potomac’s Chief of Artillery.

Sources:

[i] Allen C. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion. (New York: Knopf, 2013). Page 402.

[ii] General Worth, report from Sept 16, 1847, quoted in In Memoriam General Henry J. Hunt by David Fitz Gerald; accessed at the The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

[iii] Find A Grave – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/120195357/emily-caroline-hunt

[iv] Edward G. Longacre. The Man Behind The Guns. (Old Soldier Books, 1977). Page 69.

[v] Find A Grave – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32851558/mary-bethune-hunt

[vi] In Memoriam General Henry J. Hunt by David Fitz Gerald; accessed at the The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

[vii] Allen C. Guelzo. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion. (New York: Knopf, 2013). Page 406.

[viii] Ibid, Page 420.

[ix] In Memoriam General Henry J. Hunt by David Fitz Gerald; accessed at the The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

1 Response to Artillery: Henry J. Hunt, Chief of Artillery for the Army of the Potomac