Butler’s Decision at Bermuda Hundred

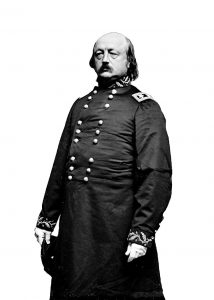

Major General Benjamin Butler’s Bermuda Hundred Campaign in May of 1864 is often dismissed quickly and simply as a failure. Commentators usually invoke Major General U.S. Grant’s quote about a “bottle strongly corked.” It is true that Butler could have moved more aggressively, especially in the second week following the landings on May 5 when his entire force was present and ready for battle.

But there is one part of the operation, the initial landing, where something needs to be said in Butler’s defense.

Butler’s troops swarmed ashore at Bermuda Hundred on May 5, 1864. Butler’s Army of the James numbered 30,000 men in the X Corps under Major General Quincy Gillmore and the XVIII Corps under Major General W.F. Smith. It was an infantry-heavy force, although some cavalry was present. The army’s objective was the cut the Richmond-Petersburg railroad and create havoc so as to draw reinforcements away from the main front further north, where Grant aimed to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia. This expedition was based out of Fort Monroe at the mouth of the James, 80 miles east.

The Army of the James achieved strategic surprise, and quickly established a beachhead. Butler paused to consolidate his beachhead before moving inland, a decision for what he has been criticized. Yet what other options are available? It must have felt lonely, that far into hostile territory with a finite number of troops available and no immediate prospect of reinforcement or other help if matters should go badly awry.

An aggressive push inland against unknown Confederate strength (not to mention into an area very close to Richmond and its garrison) would undoubtedly provoke a serious Confederate reaction; Butler had to assume major Confederate troops were on the way to appose him. Driving inland would potentially expose the army to defeat in detail, with massive troop losses that might very well compromise Butler’s ability to even hold Bermuda Hundred. Butler felt it prudent to consolidate, wait until the bulk of his army had arrived via ship, and then move inland in force. It took him a week to be ready.

There is an interesting parallel here with Major General John Lucas and VI Corps at Anzio on January 22, 1944. He also achieved strategic surprise, and chose to consolidate rather than thrust deep into the interior for fear of losing many troops and possibly the corps. In the end, his troops also got bottled up, and endured a tough siege until May.

Contemporary observers in 1864 and 1944 both chastised these men for not immediately advancing inland. But viewed from the headquarters, with your back to the sea and an unknown situation in front, and unsure plans about reinforcements, it is not an easy decision at all.

Great post! Butler also had to shed portions of his army on the way to Bermuda Hundred in order to capture City Point and garrison strategic points along the James River back to Fort Monroe. The “bottle strongly corked” line is absurd anyway, Butler had the ability to cross either the James or Appomattox at leisure.

Thanks!

I think the issue is not that there should have been no consolidation, but how much and for how long? Butler could have put most of his force to work consolidating the position, and sent one brigade to destroy the railroad.

He did probe the railroad, but found a strong Confederate reaction at both Port Walthall Junction (May 6-7), Swift Creek (May 9) and Chester Station (May 10). The Confederates also demonstrated an ability to quickly repair the rail breaks and bring up troops. As a result, Butler preferred to wait and move out in force against the railroad and Drewry’s Bluff in hopes of permanent results.

Very good Comparison on Butler – Lucas. Victory comes to the Bold. Both had to know enemy troop weakness in the area of operations

If it was hoped that his presence and movements would ‘draw reinforcements’ from the environs of Richmond and other locales, then they were bait. Were forces available to reinforce Butler as he moved forward? His forays forward were contested heavily by the Confederates. On the other hand, Lee’s army was occupied with Grant’s at points north. The Wilderness battle was raging, and Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor had yet to be fought but soon would be. Butler’s troops engaged in several skirmishes and/or battles (I think there were 5 significant ones), and had some successes and some failures. Didn’t Grant acknowledge the situation Butler found himself in, that he had a strong position for defense but was in a pretty bad position for launching an offensive? I seem to recall reading something along those lines.

Essentially yes, Doug.

Baldy Smith was the one who was overly cautious and Grenwal was late to arrive.