The Battle of Aiken: “Why spend the effort to write a book on a battle that didn’t last very long or have many casualties?”

“Why would you spend the time and effort to write a book on a battle that only lasted a few minutes and which had minimal casualties?” I wish I had a dollar for every time that I’ve been asked that question—I could probably give up the practice of law.

“Why would you spend the time and effort to write a book on a battle that only lasted a few minutes and which had minimal casualties?” I wish I had a dollar for every time that I’ve been asked that question—I could probably give up the practice of law.

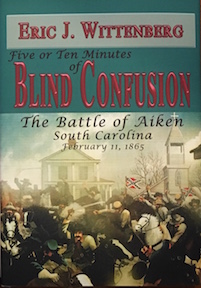

Okay, so maybe that’s an exaggeration. However, I do get asked that question constantly. A certain part of me always wants to answer that question like the old joke about why climb a mountain?—because it’s there. Setting aside my inherent smart-aleck nature for a moment, it is a legitimate question. And I’ve been getting asked it pretty frequently since the publication of my most recent title, Five or Ten Minutes of Blind Confusion: The Battle of Aiken, South Carolina, February 11, 1865 last month. (Thanks to my friends at Fox Run Publishing for a fine job of it).

For those unfamiliar with the battle of Aiken, it was the only Confederate battlefield victory during the entirety of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 1865 Carolinas Campaign. That, in and of itself, makes it interesting and worthy of study. But like peeling an onion, there are many more layers to this story that make it all the more tantalizing.

Aiken happened because Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, the famous Confederate cavalry commander, disobeyed the direct orders of his department commander, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. As his army ate and burned its way across South Carolina, Sherman tried to deceive Beauregard as to his ultimate destination in the Palmetto State, which was the state capitol at Columbia. Beauregard, faced with a severe shortage of manpower, had to be creative, and decided upon a strategy of defending the many major rivers that cross South Carolina on a diagonal as they make their way to the Atlantic Ocean. The last major line of defense was to be the Edisto River, to the south of Columbia. Counting Wheeler’s 5,000 cavalrymen, there would be barely enough troops to form a defensive position.

However, Sherman sent Bvt. Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry on a feint in the direction of Augusta, Georgia. Not only was Augusta Wheeler’s home town, it was also the home of the largest Confederate gun powder works, which made it essential to the Southern war effort. When Kilpatrick’s troopers headed in that direction, Wheeler could not resist. Instead of holding his assigned position along the Edisto, Wheeler, with 3,000 troopers, pursued.

The Confederate horsemen set an ambush for Kilpatrick in the streets of the pretty resort town of Aiken, and Kilpatrick, with a single brigade of cavalry, took the bait. Wheeler sprung his trap, and in a desperate, violent melee in the streets of the town, the Federal horsemen were forced t fight their way to safety, with Kilpatrick coming within a whisker of being captured in the process. The Union horsemen conducted a fighting retreat of about five miles to the modern hamlet of Montmorenci, South Carolina (known then as Johnson’s Turnout, a nearby railroad stop), where the rest of Kilpatrick’s command awaited their return. The reunited Union force repulsed Wheeler, who broke off and withdrew, satisfied that he had saved Augusta from the torches of Kilpatrick’s cavalrymen.

The problem was that Augusta was not Kilpatrick’s target, and Sherman had specifically instructed his cavalry commander not to go there. So, despite his battlefield victory and the embarrassment of his hated rival Kilpatrick, Wheeler had only the notion that he had protected Augusta from a non-existent threat to show for his efforts. Without Wheeler’s troopers holding their position along the Edisto as ordered, there was little in the way of effective Confederate resistance of the Union passage of the river, and Sherman’s army swept into Columbia less than a week later.

This small but tactically interesting battle—there were only a handful of mounted urban cavalry battles during the Civil War (counting Aiken, I have identified only four)—had tremendous strategic significance for the Confederacy. While a tactical battlefield victory, it was a terrible strategic defeat for Beauregard and his plans to defend the Palmetto State from the tender mercies of Sherman’s men. Mix in the fact that it was the only battlefield victory for Confederate arms during the entirety of the 1865 Carolinas Campaign, and it makes for a very interesting story. Add some good human drama, and you have a recipe for a truly tantalizing story.

Finally, I pride myself on being the master of the obscure. I often say, “the more obscure, the better.” I enjoy the challenge of tackling these obscure battles so much more than writing yet another study of Pickett’s Charge as just one example. Aiken was so obscure that when I asked Emerging Civil War editor Chris Mackowski if he’d be willing to blurb the book, he’d never heard of the battle. I love finding, investigating, mapping (we’ve mapped the battle for the first time), and telling the stories of these obscure episodes. It’s what gets me excited about my historical studies.

THAT, my friends, is why I undertook the effort to write an entire book about a cavalry battle that lasted less than an hour in the streets of the town of Aiken, and which resulted in only a small number of casualties on both sides. If we look at these battles through the microscope of just the tactics of that particular engagement but fail to examine them within the context of the overall big picture, then we miss the important lessons to be learned. As a longtime student of Sherman’s 1865 campaigns in North and South Carolina—this is my third book on some aspect of those campaigns—who continues to research Sherman’s passage through South Carolina, this was one of those small but compelling stories that I felt obligated to tell.

If the reader is interested in this phase of the CW, do not miss Wittenberg’s THE BATTLE OF MONROE’S CROSSROADS which features “Lil Kill” vs Wade Hampton. A great read!!

I always felt that small is never necessarily insignificant. Think about Chancellorsville, where Sickles’ brief fight with Jackson’s rearguard could/should have alerted the Union command staff to impending catastrophe. Or the impact of Ewell moving a few batteries of cannon away from the salient. The Butterfly effect.

Great post!

Can we look forward to your study of the Battle of Rivers’ Bridge on Feb 3, 1865, as you continue to study ‘obscure’ Carolinas Campaign conflicts? I enjoy your “Trivia Pursuit” because you write so clearly!

My Little Interior Devil would have loved to see just one battle pitting Kilpatrick against Forrest.

Mr. Pryor I believe many of us wish to have read of that duel!!!

Good explanation. Sold.

Agreed, another book out of my tight budget, lol, you NEVER let me down Mr. Wittenberg!!!