The Rise of Spirit Photography

As we near Halloween, thoughts of ghosts and spirits often come to the minds of visitors at historic places. I have recently started getting questions about ghosts, and this got me thinking about spirits “seen” by people in the 19th century and what it meant for the ones who saw them. There are accounts where people have claimed to see things they could not explain; one of the more easily documented ways that ghosts were seen was through spirit photography. But, is spirit photography real? Why did it become so popular? How was it fueled by the Civil War?

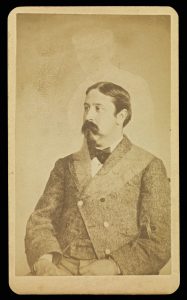

Spirit photography was first discovered by photographer, William H. Mumler after he accidentally created a double exposure of an image that he took of himself.[1] Seeing a market for it, he claimed himself a medium, and offered to help connect people to loved ones who had passed away, for a small fee. There were a couple of factors that helped to create the rise of spirit photography throughout the 1860s and 1870s: spiritualism and the Civil War.

Spiritualism arose throughout the 1840s in upstate New York, near where the Second Great Awakening began in the early 19th century. The belief of this religious movement was that the spirits of the dead not only existed, but wanted to communicate with the living and that these spirits could provide valuable knowledge on ethical, moral, and religious questions.[2] As a result of this, methods of communicating with the dead, such as seances, were widely sought after and helped spur the careers of mediums who claimed to have the ability to communicate with the dead. Two of the most famous mediums during this time were the Fox sisters. Margaret and Catherine Fox claimed to have the ability to communicate with the dead through a series of tapping noises.[3] As the news about spiritualism spread, the ability to connect with deceased loved ones no longer seemed unattainable, providing one reason for the rise of spirit photography. The another reason spirit photography became possible was the ease for photographers like Mumler to produce inexpensive photographs because of the significant increase of cartes-de-visites during the Civil War.

By the beginning of the Civil War, there were several types of images available for purchase, from daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, to cartes-de-visites. The carte-de-visite was one of the more popular imaging methods during the war for it was easier and less expensive to produce with copies of an image being made on a thicker piece of paper. With thousands of men marching away to battle, these images not only were a popular item for soldiers to give to loved ones to remember them at home, but also for the soldiers to carry with them. As a result, photographers like Mumler had hundreds of images of men and women to use to create the widely sought after spirit images by using his method of double exposure.[4]

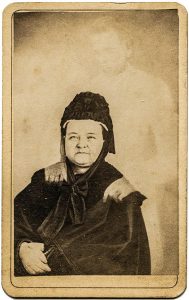

After Mumler set up shop in Boston, Massachusetts, his spirit images became incredibly popular, so much that he charged anywhere between $10-15 per image (adjusted to inflation between $300-$450 in today’s currency).[5] Many of Mumler’s subjects were common people, making it difficult for many people to recognize an individual . These images would be used to create just enough of a form so that whoever was looking at it would see what they wanted to see and feel comfort in that. Few of Mumler’s spirit images were of highly recognizable images, with the exception of Mary Todd Lincoln and the late Abraham Lincoln. Mrs. Lincoln had her image taken while visiting Boston in 1869. Since the death of her son, Willie, in 1862, Mrs. Lincoln was so grief stricken she started turning to spiritualism, visiting mediums, having seances at the White House and later her home, and having spirit images taken. She had actually become so erratic with her behavior later in life that her surviving son, Robert had her institutionalized in 1875 in Illinois for a short period of time.[6]

Mumler’s fame as a spirit photographer did not last long. As early as his first image, people were criticizing his work and claiming it as false. Yet, in an article published by the New York Sun on February 26, 1869, William Mumler is quoted to say that “he really believes that the pictures are produced by departed spirits who are attached to the sitters by affection or relationship or affinity”.[7] Eventually Mumler was arrested in 1869 on the charges of fraud and larceny, with several people, including P.T. Barnum, testifying against him. However, because the trial took a religious turn arguing the merit of spiritualism, Mumler was acquitted and returned to his practice. However, due to his spiritual and financial reputation, the spirit image that put him on top throughout the 1860s, also brought him down in the end.[8] However, spirit images live on even still today in a variety of forms and the argument whether these images are real or not will continue as well.

Endnotes:

- Clement Cheroux et. Al., The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult (London: Yale University Press, 2004), 22-23.

- Louis Kaplan, The Strange Case of William Mumler (Minneaopolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 5-6

- Barbara Weisburg, Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004), 3-4.

- Katie Scott, “Phantoms and Frauds: The History of Spirit Photography” and Frauds: The History of Spirit Photography”, Oxford University Press Blog, (October 2013) accessed, September 24, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Jean Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography, ( New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 2008), 278-280.

- Kaplan, 16.

- Cheraux et. Al., 22-23.

I am not sure if Mumler “discovered” spirit photography so much as noticed and exploited things. What about those orbs at Gettysburg?? Thanks for this interesting piece. I really love this stuff.

An interesting little piece of history. Mumler was quite the sham artist. It’s interesting that P.T. Barnum, that great promoter of hoaxes, was called as a witness by the prosecution at Mumler’s trial. It must have been quite a sideshow.

Seeing the spirit photographs in the article reminded my of an old album of late 19th and early 20th century century from my mother’s side of the family that featured a portrait of one of my great or great-great aunts or cousins and (as written underneath the photo) her ghostly “etheral self” or “etheric body” (Can’t remember which). When I saw it years ago I assumed it was a double exposure taken by accident and placed in the album as a joke by someone in the family. Maybe it was serious. And maybe Mumler or one of his henchmen took it!

It’s sad that Mary Lincoln’s grief was exploited, and evidently she was by no means alone in that experience. Thanks for an interesting article.