Did Alexander Gardner photograph Charles Tew’s corpse in the Sunken Road?

Charles Tew’s story is compelling. Daniel Harvey Hill called him “one of the most finished scholars on the continent, and [who] had no superior as a soldier in the field.”(1) Indeed he was. Tew graduated first in his class from the South Carolina Military Academy (The Citadel today) in 1846, became superintendent of the South Carolina Arsenal Academy in 1854, and founded his own military school in Hillsborough, North Carolina in 1859.

|

|

Colonel Tew commanded the 2nd North Carolina Infantry at the Battle of Antietam. This regiment occupied the left of George B. Anderson’s brigade in the Sunken Road. During the fight, Anderson, Tew’s superior officer, was wounded and carried from the field. Word reached Tew of his ascendance to command. Immediately upon receiving it, Tew fell with a bullet to the head, mortally wounded. He later died on the battlefield.

Rumors circulated about Tew’s death and it was not until 1874 that the Tew family confirmed that their son perished at Sharpsburg. To this day, it remains a mystery where his remains lie. Only recently (in 2015) did the sword Tew carried into action finally surface.(2)

Perhaps the mystery of Tew’s final whereabouts and the long-held and recently answered question regarding his sword have prompted an interest in tying up as many loose ends of the story as possible.

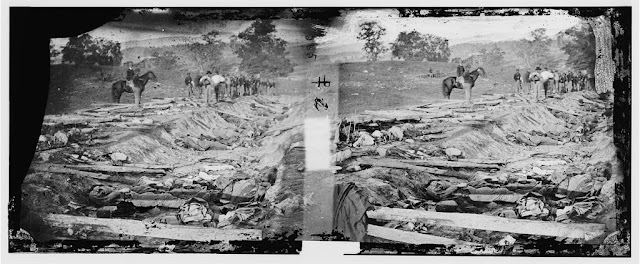

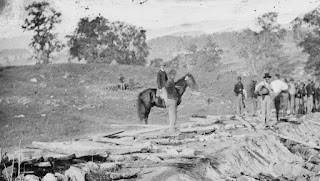

While recently on a tour at Antietam, an oft-repeated query came up about whether or not Charles Tew’s remains appear in a photograph that Alexander Gardner captured of the Bloody Lane (below).

Two theories exist as to which of the bodies in this image might be that of Charles Tew. The first postulates that the man in the right foreground of the image laying against the bank of the Sunken Road is Tew. A second thought hypothesizes that his remains lie further down the lane, his bald head facing towards the camera.

I believe that Charles Tew is neither of these men and that he is not even in the picture. The soldier lying in the right foreground did die of a head wound like Tew, as evidenced by the blood dried on his face. However, this man has a full head of hair, the opposite of the extant images of Tew. Additionally, a cartridge box slung across this man’s shoulder, the presence of a cap box and what appears to be a bayonet scabbard, as well as a lack of any insignia, clearly denotes this man as a private soldier rather than an officer like Tew.

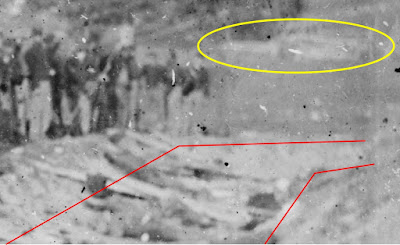

The soldier with the bald head, who lies further from Gardner’s lens, is difficult to prove that it is not Tew based on an examination of his remains, even when zooming in on the high-resolution plate. The bald head is apparent but no other details, such as insignia or any signs of a head wound, can be conclusively picked out. Thus, other clues must be used to show that Tew is not in this image.

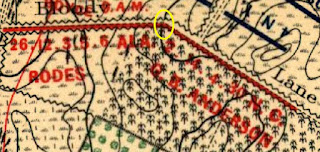

Confusion has existed over exactly where in the Sunken Road Alexander Gardner captured this scene. I think photographer and blogger Dave Valvo has settled that question for good. Mr. Valvo places this image in the east-west portion of the Sunken Road between the Hagerstown Turnpike on the west and the point where the Sunken Road bends to the southeast. The bend in the road is visible in the left half of Gardner’s photo as is the worm rail fence that bordered the Roulette Lane to the north. These additional pieces of evidence cement in my mind that Gardner set his tripod near the current location of the 130th Pennsylvania’s monument in the Sunken Road.

The 2nd’s left connected with the right of the 6th Alabama, and the two regiments linked together at the bend in the road. Gardner’s image, therefore, shows the position of the 6th Alabama Infantry rather than the 2nd North Carolina’s former line. However, that does not entirely settle the question for good, as one member of the 6th Alabama implied that Tew fell within their lines. Ezra Carman noted that the 2nd North Carolina’s second company from the right was positioned at the intersection of the Roulette Lane and the Sunken Road.(3) Placing the image in this location is critical to determining whether or not Tew’s body is somewhere in the field of view. The 2nd North Carolina Infantry was never in this section of the road. Instead, it occupied the portion of the lane around the bend visible in the photograph where the Sunken Road makes a southeast turn.

|

|

|

|

Colonel John B. Gordon claims in his Reminiscences of the Civil War that Tew fell mortally wounded during the first Federal volley fired into the lane and while the two colonels conversed.(4) Gordon’s account of the Sunken Road should be read under scrutiny and much of his story does not hold water.

Charles Tew received his wound not at the first volley while speaking with Gordon in the 6th Alabama’s position but instead much later in the fight. Tew’s brigade commander, George B. Anderson, was wounded at approximately 10:30 a.m., roughly one hour after the fight for control of the Sunken Road commenced.(5) Anderson dispatched one of his couriers (Baggarly was his last name) to find Tew and inform him of the need for a change of command. Baggarly could not locate Tew and found Col. Francis Marion Parker of the 30th North Carolina, Anderson’s right regiment. Parker sent his adjutant, Fred Phillips, to find Tew. Phillips darted down the back side of the four North Carolina regiments and found Charles Tew lying down in the road. Phillips informed Tew of his ascendance to brigade command. To acknowledge that he heard Phillips, Tew stood up, removed his hat, and bowed in Phillips’ direction. While in motion, the fatal bullet struck Tew in the head.(6) One contemporary source cites 11:00 a.m. as the time of Tew’s wounding, well after the first volley was fired.(7)

Matthew Manly, a veteran and historian of the 2nd North Carolina, claims that Tew was not with his own men when he fell, thereby disputing the sources used above. Regardless, Manly clearly describes that after Tew was hit, he was “placed in the sunken road near the gateway of the lane that leads to the farm-house, with his back to the bank nearer the enemy.”(8) This lane is the Roulette Lane and the intersection of that lane and the Sunken Road, the location of Tew’s body, is not visible in Gardner’s photograph.

One more argument could be made that perhaps Tew’s body was moved to the line of the 6th Alabama and was then captured by Gardner. This is not to imply that Gardner himself might have moved the body but that it may have been relocated in the chaos of the continued action or by the Federal burial details seen overlooking the lane. That also seems unlikely, though.

|

|

Details of the photo reveal that the fields over which the Union soldiers attacked the Sunken Road are cleared of debris and bodies. The Union troops dispatched on burial detail buried their own dead first and were probably just about to begin burying the enemy dead in the road when Gardner captured the scene. The dead Confederates in the road lay among the scattered debris of war and the soldiers themselves are not laid out in rows as burial details were apt to do. Gardner photographed these Confederate dead as they fell. He shot a very raw scene in the Sunken Road.

Based on my research and analysis, Charles Tew’s body cannot be seen in Gardner’s image of the dead Southerners in the Sunken Road. Locating the photograph demonstrates that the corpses in the scene belong to the 6th Alabama Infantry. Tracing the movements of Charles Tew on September 17, 1862, conclude that he was not shot among the Alabamians but alongside his own North Carolinians.

Notes

1. OR, vol. 19, pt. 1, 1,026.

2. NCPedia, s.v. “Tew, Charles Courtenay,” https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/tew-charles-courtenay.

3. Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Antietam, 243.

4. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War, 89.

5. Carman, Antietam, 262.

6. Ibid.; Parker, “Thirtieth Regiment,” in Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War, 1861-’65, vol. 2, 499-500.

7. “From Our Army,” Semi-Weekly Standard (Raleigh, NC), October 1, 1862.

8. Manly, “Second Regiment,” in Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War, 1861-’65, vol. 1, 167.

This article was reposted from the Antietam Brigades blog.

Civil War photographs tell a million stories if you look closely enough. Thanks for looking at this one.

Thanks, Chris. It was fun to take a look at. There’s even more stories in it I think I have found, so stay tuned!

Fascinating article, Kevin. Gardner’s moving images are what inspired me to focus on the experience of the Sixth Alabama in my book Six Days in September. I always wondered about the fury of the fighting there and felt compelled to describe it from the perspective of the men in the road. It was, to say the least, a very difficult and emotionally-challenging chapter to write. It had to capture the horror of the scene conveyed in the photos.

Thanks, Alex! I think looking at this image and thinking about the 6th Alabama really shows what they experienced there in the road. I enjoyed reading your chapters about the 6th in the Sunken Road.

Once one begins looking at these images, the horror sort of melts away a bit. They become real men, and supposing about their real lives is a source of endless fascination. But then the horror returns fivefold–MY GOD! These were real men! Well done, Kevin.

Thanks, Meg!

The head and body of Col. Tew can be seen in “Shadows of Antietam”, page 46. His bald head is in the middle of the lane directly to the right of the horse on the north bank.

Believe the hair one sees that seems to be Tew’s is in fact the hair from the head pf the headless body on the other side of the trench. The head partially obscures Tew’s face.