Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader

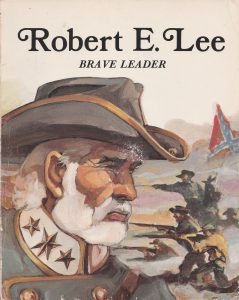

In the 1980’s and 1990’s I was periodically given a catalog for Troll Associates, which published children’s books. Among them were various history books. In the library I had already checked books from the World at War series, the first being The Battle of Stalingrad. Troll though did not have as many military topics. Then one day I spotted a book on Robert E. Lee. The cover was odd. Lee looked like Kenny Rogers and I knew even then the battle shown on the cover was from an evocation, if wildly inaccurate, painting of the battle of Wilson’s Creek. Still, I was eager to read it, making it the first Civil War book I ever completed

The book was titled Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader. It was mostly about Lee’s difficult childhood dealing with the disgrace of his father and the need to restore honor to his family. It also dealt with the aspects of his youth that contributed to his later leadership abilities. Although not exactly what I wanted, it was touching, and far more than another children’s book about Lee from the 1970s that dealt with each battle. I read that one after Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader and liked it more, yet Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader stayed with me over the years. I cannot even recall the other book’s name.

Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader was visually effective. The illustrations by Dick Smolinski filled in the holes that the prose by Rae Bains could not convey. They were also adult and emotional. You see Henry Lee leaving his family in disgrace, looking down from a ship bound for the Caribbean. There is a young Lee determined upon a military career, followed a few pages later by an image of a dead Confederate soldier, the cost of that decision. Those images and others, including a young Lee visiting a clown show, have remained with me.

Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader was published in 1986 as part of a series of biographies meant to teach children important personal lessons. The other titles included Gandhi: Peaceful Warrior, Clara Barton: Angel of the Battlefield, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom, Thurgood Marshall: Fight for Justice, Jack London: A Life of Adventure, and Benito Juarez: Hero Of Modern Mexico. There were also books on Martin Luther King Jr., James Monroe, Louis Pasteur, Babe Ruth, and Christopher Columbus. One can debate the place of each. Certainly choosing Monroe over the other presidents is odd. Overall though, it represented a kind of late twentieth century multiculturalism. It was itself an echo of John Pershing’s civic-nationalist musings after the American victory at San Juan Hill: “White regiments, black regiments, regulars and Rough Riders, representing the young manhood of the North and the South, fought shoulder to shoulder, unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by ex-Confederate or not, and mindful of only their common duty as Americans.” It offered a reconciliation between sections that did not ignore racial justice. It permitted honoring Lee right along with King, Barton, and Ruth. One can see this vision in Ken Burns’ The Civil War and the novel The Killer Angels.

Lee was one of my heroes growing up. I used Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader to do a tape cassette recorded interview. I was Lee and my mother, Patricia Acker Chick, asked me questions like it was a news report. I got an A. It was one of the first school projects that I excelled at. Years later I received a framed picture of Lee with his farewell address, which I once knew by heart. I learned it first by buying a copy of the address in a French Quarter shop. It was sold right next to the Gettysburg Address and Declaration of Independence.

If I was asked which reputations I have seen fall the most in the last ten years, Lee would be up there with Sigmund Freud and Harvey Weinstein. Obviously, and despite some high profile removals, he still has admirers, even if those admirers no longer have large microphones. All of those personal admirers I know are older or the same age as myself. I might be part of the last cohort of Southern men taught to venerate Lee. I say might because the future is unknown and stranger things have happened. For now though hardly a major newspaper or magazine offers editorials in his defense. In a November 21, 2018 Washington Post op-ed, Stanley McCrystal wrote that he took his painting of Lee down and “sent it on its way to a local landfill for its final burial. Hardly a hero’s end.” Lee was denied even the mild indignity of being donated to the local Goodwill.

My respect for Lee has remained, even if the veneration faded long before his current vilification. Lee seemed less relevant over time and he was no longer a personal role model I could draw strength from. I found men such as William Tecumseh Sherman and P.G.T. Beauregard more personally compelling over time, not as heroes but as stories I could relate to. Regardless, when Lee’s statue came down in New Orleans I felt cold. A fixture of the city and my youth was gone, and removed with none of the magnanimity Ulysses S. Grant showed at Appomattox. I began to ask what did Lee mean to me or anyone else? Part of this side quest was reading Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader for the first time in decades. I still have no hard answers.

There are in my experience three different versions of Lee which I call the defiant, the traitor, and the reconciliationist. The defiant is celebrated as a battle commander who despite being out-numbered, won nearly every battle. That was the Lee of my father and the Lost Cause die-hards. The traitor is a man who fought to maintain a slave-society and who should have been hanged. That is the Lee of Mitch Landrieu and an emerging consensus. The reconciliationist is a tragic figure who fought to defend his home state. In this version he is respected as a worthy and honorable adversary who did much to bind the nation’s wounds after four years of conflict. That is the Lee of Bains, who ends Robert E. Lee: Brave Leader with a line that few would type in 2018: “His passing was mourned in the North as much as the South, for the nation had lost a great man.”

The tragedy of Lee, and even Gandhi, Tubman, King, and Columbus is that they are not people but symbols. They are monuments, as much in paper and image as in stone. The trouble beyond losing whatever human connection we have is that their flaws and shortcomings, whatever they may be, are more glaring when finally revealed. If Lee suffered a loss of status it is in part because some people constructed a simulacrum of the man. Being a symbol meant in time Lee became an anachronism, and those who railed against him or defended him were not dealing with Lee but instead their version of Lee. It would be tragic if in place of falling Lee statues we create a new myth where Lee is a villain in an American melodrama who is finally defeated by simulacrums of Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln.

Lee was a great man, a gentleman and is still a hero. He, and the south fought for the ideals our founding fathers gave us through the constitution and the bill of rights. One only has to research the writings of the founding fathers, especially Thomas Jefferson, to see they believed the power of government laid with the people of each state. They were as well fearful of a strong federal government that would become over bearing and would lead to tyranny. The government our founding fathers gave us was lost to a government they feared.

You unintentionally fall into the very problem identified in the post by putting Lee on a fallacy-ridden pedestal. You would benefit greatly from reading (1) Lee’s letter to his son in January 1861 and (2) the book Reading the Man. You also clearly misunderstand the reasons for secession.

Bravo Robert!

Dear Robert:

Thank God Lee and the Confederates lost the CW. The United States of America remained the United States of America and slavery was abolished.

As for your comment about our government now being a tyranny: We still have all the freedoms laid out in the Constitution, including the First Amendment’s freedom of speech, which allows folks like you to espouse radical, historically-challenged views without the threat of retaliation from government.

Well said. In addition, Mr. Rainey should actually read the thoughts of several of the “founders” other than Jefferson on the subject he refers to. Lee’s January 1861 letter to his son was pretty clear – as much as it might be inconsistent with certain modern political agendas.

Robert E. Lee has been since my youth and will always be my hero. Yes, I know he was a flawed man with many short comings but his personal character has always stood out to me. No amount of the hatred now being dumped on him will ever change my mind about my hero.

ROBERT E. LEE by David McDowell, illustrated by William M. Hutchinson was one of my first books. Copyright 1953.

I still enjoy rereading this book every once in a while.

Tim

Five generations of my family have borne the name Lee, beginning with the first male child born following the War. The most recent is one of my grandchildren. Lee has not changed, only public opinion.

Were the Eighties really that long ago?

Oh yes they were. I recall in 2011 watching the film Action Jackson and finally feeling like I lived a world that was quite different.

Interesting, and good, article here. So much has been written over the years on this subject. Much of that is under renewed scrutiny due to controversies over things like Confederate monuments. Separating the REAL history from that of the revisionist kind will always be a challenge.

Lee, and others, back then faced challenges and decisions that make me shudder to consider. It is quite easy for all of us today to sit back in our environmentally controlled bunkers (LOL) and impart our ‘wisdom’ so long after the fact. Lee’s pre-war musings indicate that he vehemently disagreed with any dissolution of the Union, and that if that occurred, he would not take part. Yet he did take part. As did MOST others placed in such a position. Whether he had a change of heart, was convinced by a close confidant, felt ‘forced’ to by blood and/or other ties, so what? He did it. It happened!

I mentioned possible attempts at ‘revisionist’ history. The pursuit of truth will often result in the implementation of ‘presentism’, which is defined as the interpretation of past events through the lens of modern day values and attitudes, or words to that effect. That is a trap that is best avoided, because the ACCEPTED attitudes and norms back then are vital to understanding and properly interpreting what really happened, and why it happened. However, I acknowledge that learning relevant facts and trying to determine the truth will often result in assigning blame and condemnation concerning those past events, and in re-evaluations of accepted beliefs. That’s what the historians have to do. Throughout history people who were deemed to be ‘good’ turned out to be the opposite as more facts are known. And vice versa. Gosh, we had that “three fifths of a person” passage in the original Constitution. How is THAT viewed today?

So, with all that said, when it comes to RE Lee, was he evil? Was he ‘great’? Do we judge him on his ‘character’? On his military leadership and acumen? On his decision to do what the vast majority of others did and adhere to what their states decided to do as far as secession?

My view is that the times were quite complex, and Lee reflected those complexities. I personally believe he was a good man caught up in a bad period of our history. Slavery was a horrible institution, but if anyone truly wants to be ‘fair’ in their rightful condemnation of that, then endeavor to hold ALL accountable back then, from those who owned plantations, from the slave ‘merchants’ who supplied ‘product’, and the TRIBES on the African mainland who took part by doing the actual capturing and selling of those who would become the actual slaves, and all the others! Lee was a slaveholder, and history holds that against him, among other things. It is easy t do so via that ‘presentism’ I mentioned earlier, but again, Lee was a reflection of the times he lived in.

In closing, thank GOD none of us had to make the kinds of decisions he and so many others had to make back then. On my ‘list’ of those who I would love to be able to go back in time and converse with, he is high on that. I find him a most interesting man..

Sorry for the length of that. I didn’t grasp its length.

An excellent essay and I concur. Lee’s pedestal is much more than fallacy-ridden, though certainly fallacies are involved in regards to Lee, just like they are with Lincoln. However, if one wants to argue that Lee’s character and reputation is mere fallacy, then one may want to consider that the fallacy could have started when Lincoln chose him first to take command of Union forces. Or maybe the fallacy began when Lee graduated second in his class from West Point without one demerit. Then again, the fallacy of Lee’s character may have begun with Union General Joshua Chamberlain at Appomattox who wrote:

“I turned about, and there behind me, riding between my two lines, appeared a commanding form, superbly mounted, richly accoutered, of imposing bearing, noble countenance, with expression of deep sadness overmastered by deeper strength. It is none other than Robert E. Lee! … I sat immovable, with a certain awe and admiration.”

Perhaps it began with Union General Morris Schaff’s opinion of Lee when seeing him at the surrender:

“He was one who, though famous, was not honeycombed with ambition or tainted with cunning or cant, and though a soldier and wearing soldier’s laurels, yet never craved or sought honors except as they bloomed on deeds done for the glory of his lawfully constituted authority; in short a soldier to whom the sense of duty was a gospel and a man of the world whose only rule in life was that life should be upright and stainless. I cannot but think Providence meant, through him, to prolong the ideal of the gentleman in the world . . . It is easy to see why Lee has become the embodiment of one of the world’s ideals, that of the soldier, the Christian, and the gentleman. And from the bottom of my heart I thank Heaven . . . for the comfort of having a character like Lee’s to look at.”

But U.S Army Lt. General Winfield Scott may have started the fallacy:

“Robert E. Lee is the greatest soldier now living, and if he ever gets the opportunity, he will prove himself the greatest captain of history.”

Perhaps if we step away from condemning 19th century individuals for failing to conform to 21st century standards of morality, we can arrive at a truer picture of those individuals. Apparently, Lee’s undying status as a truly American icon of honor and nobility is much more than “fallacy” or “myth.”

Well put!

Thank you.

To be clear, the “fallacy-ridden pedestal” I referred to was the one built by Mr. Rainey. That comment relied on several politically motivated fallacies which actually do a disservice to Lee. His letter to his son is an excellent example which undermines those fallacies. In effect, Mr. Rainey converts Lee into exactly the type of misleading stereotype addressed in the post. Anyone who thinks Lee was perfect is also actually doing a disservice. For example, do we still not accept the unchallenged fact that he whipped slaves? And there were plenty of folks around in 1860 who thought that was a moral wrong. As a sidebar, we should be wary of accolades bestowed in the late 19th-early 2oth centuries on a public figure who died decades earlier. Chamberlain and Schaff were writing well after Lee’s death in an era of “reconciliation” – in fact there is good reason to believe that Chamberlain imagined or embellished some of the events connected to the surrender. The point of the post is a good one – let’s stop assessing Lee from the standpoint of a symbol. That’s a two-way street.

Scott’s accolades were contemporary, I believe. Lincoln’s offer was in 1861. Lee’s West Point record was long before that, as well as was the establishment of his credentials during the Mexican War. All before reconciliation and Lost Cause sentiments. Chamberlain and Schaff were writing later, but were recounting their own thoughts at the time of surrender. Were they involved in a conspiracy or lying? That would disparage their character, not Lee’s. The New York Times wrote the following (in part) when announcing Lee’s death in 1870:

“the career of Col. Lee had been one of honor and the highest promise. In every service which had been entrusted to his hands he had proved efficient, prompt and faithful, and his merits had always been readily acknowledged and rewarded by promotion. He was regarded by his superior officers as one of the most brilliant and promising men in the army of the United States. His personal integrity was well known, and his loyalty and patriotism was not doubted. Indeed, it was in view of the menaces of treason and the dangers which threatened the Union that he had received his last promotion, but he seems to have been thoroughly imbued with that pernicious doctrine that his first and highest allegiance was due to the State of his birth.”

Again, a contemporary account.

I know of no one who thinks Lee was “perfect”. He was human, which makes his “pedestal” reputation all the more interesting. Yes, he has been put on a pedestal that would embarrass him and which he would not want. But there are far too many contemporary accounts regarding Lee’s reputation and the admiration that Lee garnered from friends and foes alike, despite what revisionist historians so desperately are trying to accomplish. Frankly, their efforts are in vain and bunk.

That’s correct regarding Scott’s statement Mr. Williams. Note that the statement was confined to Lee’s military attributes (probably based in large part on Lee’s staff work under Scott in Mexico). It didn’t range into the “Marble Man” turf populated by others. Scott, a Virginian, also rejected Lee’s notion that he could take the sidelines, stating “”I have no place in my army for equivocal men.” Scott stood by the oath he had taken.

The Times piece was an obituary penned in the Victorian age at a time when efforts were already underway to effect a reconciliation between former enemies. You establish a false dichotomy – Chamberlain and Schaff need not have been “lying” (although if you look into things more closely you will find that Chamberlain not only appears to have embellished what took place on April 12, 1865 but probably did the same with what happened on July 2, 1863 – causing post-war disputes between himself and other members of the 20th Maine). Instead, both were expressing subjective opinions which fit with Victorians’ public respect for the deceased – especially, again, in a climate where the perceived “good” was national reconciliation.

Thanks Mr. Foskett. We’ll agree to disagree. I see this whole effort of disparaging Lee’s character and reputation in the larger context of the faddish trend of trashing American heroes – everyone from Lee, to Jefferson, to Washington, to Custer, to Columbus to Teddy Roosevelt. While all these figures certainly had their moral failings (as did JFK, LBJ, FDR and many others), I find the constant moral preening boring, juvenile and self-serving. I’m not accusing you of that, just an observation in general. Thank you for the civil discussion. Merry Christmas to you.

Thanks, and same to you. I don’t disagree that to some extent revisionism is done for revisionism’s sake. But I think it has to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. For example, I can distinguish Robert E,.Lee from Douglas MacArthur, who in my humble opinion is one of the most over-rated figures in US history – both from a strictly military perspective and as a man. Ironically, it can head in the other direction, as well. George Thomas and McClellan are two guys for whom there’s now something of an “over correction” going on. Always better to assess these folks as objectively as possible.

Dear Richard:

Let’s talk a bit about the “faddish trend of trashing American heroes. . .” Ulysses S. Grant was rightfully a hero (at least in the North) for years after the the CW. But a well-orchestrated campaign by Lost Causers resulted in the reputation of the CW’s greatest general being “trashed” for many decades. The historically-challenged Lost Causers’ campaign was so successful that even many Northerners believed Grant was an oaf and a butcher.

Only in the past few decades have more and more historians started to give Grant his due – as the CW’s premier commander, a general who was a superb tactician as well as strategist who brilliantly used foot soldiers, cavalry and warships to win victory after victory.

Bob,

I think you have to consider other perspectives about Grant.

The first is that bashing Grant was not wholly a Lost Cause phenomenon. Much of it had to do with a very corrupt presidency and Grant’s complicity in that corruption, as well as the ultimate failure of Reconstruction. On the later, Grant’s role in pulling out of Reconstruction has been long underplayed. In addition, you have the Plains Wars. These are all reasons to find Grant lacking and none of those in particular are Lost Cause in nature.

As a military commander, Grant was as error prone as the rest, and often showed tactical inflexibility and detachment. Grant was good at operational maneuver, strategy, army politics, and logistics. Calling him tactically “superb” though is quite a stretch.

I fear Grant is becoming the new “marble man.”

Sean: Regarding Grant’s tactical performance, much the same could be said of the legendary Thomas Jackson – in fact, his reputation still seems to outshine Grant’s even though he was actually an even more mediocre tactician – I give you First Kernstown, McDowell, Port Republic, the Seven Days, Cedar Mountain, Brawner’s Farm, Day 2 at Second Bull Run, and Hamilton’s Crossing.Even the flank attack at Chancellorsville was managed in such a way that (1) it would have been acted on by anybody but Howard, Devens, et al. after the march was discovered and (2) it resulted in Stonewall having to reconnoiter in the dark, Jackson has always been, and remains, a Marble Man despite this tactical record, his harmful concealment of intentions and plans from subordinates, and his often unnecessarily fractious relations with those subordinates.

Hello Bob. I hope you are well. Yes, what you say is true. Interesting, however, is how Lee reacted to such “trashing” of Grant:

“Sir, if you ever presume again to speak disrespectfully of General Grant in my presence, either you or I will sever his connection with this university.”

I think Grant’s greatest asset was his superior numbers and supply chain. Those factors can make anyone look brilliant.

*were* his superior numbers and supply chain. 😉

I very much agree with you about Jackson. He seemed at his best when left to his own devices, but when under direct supervision stumbled badly. He was a very erratic commander, but he did have some considerable talents.

In terms of grand tactics, I am most impressed by George Thomas

Mr. Williams: I understand why one would be cautious about extolling Grant’s tactical acumen but i think you may be falling into a bit of the oversimplification/vilification process yourself when you state “Grant’s greatest asset was his superior numbers and supply chain.” That’s objectively not true, even if it might fit Jubal Early’s “Lost Cause” spin about why Lee lost. Grant’s successful maneuvering against Vicksburg in April-May, 1863 was due to good operational insight and execution. He also outmaneuvered Lee more than once in the Overland Campaign by flanking to Lee’s right. If the sluggish Army of the Potomac had executed in a timely fashion at Spotsylvania, Lee would have been in a large bucket of trouble. The operational maneuvering ended up with Lee entrenched around Richmond/Petersburg – exactly where and how he didn’t want to be. That wasn’t due just to larger numbers or logistics. At that point Lee’s only real hope for salvation was political in the North. If we’re going to be objective about Lee, let’s also do that about Grant. . .

Growing up in Wisconsin, I never “encountered” Lee growing up as a hero or any other way. I didn’t have any particular opinion until I first became engaged in reading / learning the civil war. By the time my reading became more serious I was in a military career. I couldn’t really relate to the idea of resigning one’s commission and what appeared to me as violating an oath. I grant that Lee was “brave” personally and a “leader”. Beyond that, though not any way a hero to me. As seen by his acceptance of a transfer to cavalry for promotion he was certainly not above the careerism of his day. It also seems like the way in which he received command of the ANV and some of his actions as army commander compared to the national strategic needs of the CSA make his greatness suspect. (To be fair most commanding generals had tunnel vision when considering theater vice national concerns and priorities.) As far as his operational art I consider him competent, but I don’t see innovative, and I don’t think he learned/improved his art over his tenure as compared to union generals.

As far as MacArthur, here there was somewhat of a Wisconsin connection, though I don’t think he was “venerated” in any way. Since I now live next to the home of the 25th Infantry Div in Hawaii I’ve been curious about their history, so have done some study of MacArthur’s WWII and Korean War campaigns. In particular for Korea I’m not impressed. Keeping X Corps separate from EUSA I just don’t see the rationale for, and in hindsight (and I think contemporary sight) the backloading of X Corps into ships at Incheon for amphibious assault at Wonsan just doesn’t make much sense to me.

Agreed on your MacArthur comments.

In terms of Lee as a general, I have a few thoughts, which may one day be a post. Here is something I wrote in forum at boardgamegeek

“The more I have studied the war the more impressed I am by Lee as a strategist. He was not great, but I would argue only Sherman was a truly brilliant strategist in the conflict. Grant, Lee, Bragg, Beauregard, and McClellan also showed considerable talent.

When Lee was the advisor to Davis he supported concentrating armies in the west after Fort Donelson fell. He also understood that threatening DC by way of the Valley would scare Lincoln and weaken McClellan.

Once in command in Virginia he understood that he faced the largest and best equipped Union army. He knew that a sudden major defeat would lead to the fall of Richmond, which would be a blow the CSA could never recover from due to Richmond’s importance in terms of morale, politics, and munitions. He opposed transferring men out of Virginia because he tacitly implied the generals out there would waste his men. He was correct.

He understood that a major victory over the Union could lead to dramatic results in the east. He came close to this a few times, but ultimately he was severely outnumbered, often 2 to 1. Bragg, Pemberton, Hood, and Johnston enjoyed a better odds ratio but came up short.

That Lee was able to hold Virginia for three years against the cream of the Union war effort is an accomplishment few have equaled in American military history. It was based on a coherent strategic calculation. We can debate its merits. My two favorite Civil War generals are Sherman and Beauregard and both thought Lee was not a particularly good strategist. But it was a coherent strategy, which I cannot say for a lot of his contemporaries.

I am not saying Lee did not have flaws, only that the denigration of Lee as a strategist has often seemed half-baked and in this regard he deserves another look.”

Scott: I’d recommend Hampton Sides’ new book On Desperate Ground, about the Marines at Chosin in November, 1950. It’s a nice, succinct summary of the posing fraud that Dugout Doug really was – including his comical aerial “surveillance” of the Yalu, leading to his “conclusion” that no Chinese forces had crossed into Korea. As happened in the Philippines and the Southwest Pacific, a lot of American kids paid for his arrogant incompetence. All of that is entirely aside from the fact that in 1944 he was orchestrating a clandestine Presidential campaign while commanding forces in the field. Not even McClellan pulled that stunt.

Overall, these were some great comments and thoughts. I would hit the Like button more but cannot because wordpress does not seem to want me to do it.

Sean, et. al.

Re. Grant’s generalship: As you say, Grant – like virtually every other CW general (both North and South) made his mistakes. Yet, Grant’s never-say-die attitude more than made up for most of his missteps on the battlefield (Shiloh and the Wilderness, for example). Also, his Vicksburg campaign was the most brilliant of the war. Lee, a great tactician, never came close to matching the Vicksburg campaign. Grant’s use at Vicksburg of foot soldiers, warships and cavalry showed a tactical and strategic vision unsurpassed in the CW. And he won the war by beating the Confederacy’s best general and best army,

Re. Grant’s presidency: This part of Grant’s career is getting a much deserved rehabilitation, too. Of all the post-CW presidents, he stands alone as the staunchest defender of black civil rights. He took on America’s most vicious domestic terrorist organization – the KKK – and won! He fully endorsed and defended (sometimes with the use of troops) ex-slaves’ right to vote, own property, serve on juries, education their children, etc. – all basic rights that were violently opposed by many post-war Southern white racists. There was some corruption during his presidency, but it was overblown by Lost Causers. Many presidential administrations have faced similar corruption scandals. And Grant was never personally tied to any of them. In fact, his personal intervention brought an end to attempts to corner the silver (or was it the gold) market, even though one of his relatives was a part of the scheme.

Folks, I could go on and on, but my fingers are getting tired from typing so much.

I think you are confusing tactics with operations. Grant’s Vicksburg campaign was operationally brilliant and daring. Tactics though would be the battles fought in that campaign. Truth be told, he was also at his tactical best in the Vicksburg battles. Much less so in Virginia 1864 or even Shiloh and Chattanooga.

Grant had a tendency towards unforced errors in battle that were covered by numerical superiority and good subordinates. Shiloh is a case and point. I do not think him tactically inept, but perfectly average. His true strengths as a commander were elsewhere.

In terms of Grant’s presidency, the man who really went after the KKK was Amos T. Akerman, who likely had to resign because of his investigations of railroad corruption. Grant did favor black voting and civil rights, but he was more interested in cultivating business interests and the power of the Republican Party. He did nothing for the Chinese in California, did little to stop encroachment on the lands owned by the Plains Indians, and when the Panic of 1873 hit he cared much less about the plight of Southern blacks. Most redeemer governments came to power under Grant’s watch and he decided not to prop up Reconstruction governments in his final years. He refused to intervene in Arkansas and Mississippi. Why he did not is complicated. I do think Grant’s scandals seem less important in our age because this is another time of corruption and cynicism. In the mid-20th century, they were central to people’s thoughts about Grant, and that was a time when people had far higher standards for government should do and should be.

Saying “Many presidential administrations have faced similar corruption scandals” does not pass the test. First off, guilt is not absolved by being among the guilty, and second he actually went far beyond most presidents before or since in terms of the number and seriousness of the scandals. To be fair to Grant, he was not as personally involved as say Richard Nixon, but he did have some knowledge and committed perjury to defend friends such as Babcock. Which goes back to Grant’s propensity during the war to reward friends, regardless of their talent, while damning enemies, both real and imagined.

If one does not think Grant was a military genius or you think that his presidency had major problems, it is not inevitably a result of the Lost Cause. That stereotype of Grant was as a butcher and a well meaning political imbecile. The evidence does not support either argument, although like any untruth it is more an extreme distortion than an outright fabrication.

As is often the case, C. Vann Woodward had the best overall take: https://www.americanheritage.com/content/lowest-ebb

Bob: That’s a good point about Grant’s work with the USN early on. The cooperation between the Army and the Navy in the Henry/Donelson Campaign and later in the Vicksburg Campaign was a model for the time. McClellan has been credited with that but the reality was that his A-N cooperation was pretty much limited to getting his army to the Peninsula – and providing a “safety net” and lunch room for Mac when the heat at Glendale became too much on June 30, 1862. 🙂

Dear Sean:

I didn’t confuse tactics and operations (or even strategy) at Vicksburg. As you correctly wrote, all of them were outstanding. The closest Lee came to conducting a similar successful campaign was Seven Days. However, Seven Days wasn’t nearly as complex (no use of navy and only limited use of cavalry – nothing like Grierson’s raid through central Miss.) Also, the AofP escaped Lee during Seven Days and even defeated him at Malvern Hill. Grant at Vicksburg trapped and captured an entire enemy army of 30,000.

Your comments about Grant escaping defeat because of good subordinates couldn’t be more off base. While he had some fine subordinates in the Western Theater, his plans were repeated thwarted by incompetent and indecisive subordinates in the Eastern Theater. If he had had competent subordinates in the AofP, he would have ended the war in mid-1864, instead of April 1865.

While Grant did enjoy numerical superiority in most of his campaigns (except Vicksburg where both sides were about even), Grant was always on the offensive. And as I’m sure you realize, generals generally need far more troops during offensive operations than in defensive ones.

It’s interesting that you should credit Grant’s subordinates for his successes. Most Lost Causers don’t do the same for Lee. To Lost Causers, Lee did it all almost on his own. And, of course, he lost Gettysburg, they say, because of Longstreet. (What a joke.)

As to Grant’s presidency, it’s interesting you again credit one of his subordinates, not Grant, for defeating the KKK domestic terrorists. But when it comes to scandals, you blame Grant himself and don’t mention his subordinates (the ones who were actually at fault). Do I detect a serious double standard here?

While Grant’s Indian policy was not particularly successful, he’s not alone here. Failed policies toward American Indians have plagued virtually all administrations right up to the present time. At least with Grant, he made a good-faith effort to improve the Indians’ lot, although this effort ultimately failed.

You accuse Grant of being interested in politics. Sean, in case you don’t realize it, POLITICS has been a central core of every presidency our country has ever had. Every single one.

As to other presidencies facing scandals. It would take too long to list the multiple serious corruption scandals that hit many other presidencies. In fact, I can only think of a handful of presidencies that have been scandal-free.

But there is a difference in the Grant scandals and those of most other presidencies. Grant faced a decades-long negative campaign, i.e. Lost Causers, to exaggerate and keep before the public his administration’s scandals. Unfortunately for Grant and this nation’s historical memory, the Lost Causers’ factually challenged campaign was a resounding success until recent years.

Bottom Line: Grant remains, by far, the finest general of the CW. And his presidency, while not perfect, logged many successes (most of them diminished or completely forgotten through a highly successful – but historically challenged – campaign by Lost Causers).

Bob,

I started writing this reply:

“Grant could capture an army at Vicksburg because Pemberton decided to fix himself to that position. Pemberton had chances to escape and refused them all. McClellan was not fixed to a post. In fact, until 1865, all major surrenders (Fort Donelson, vicksburg, Harper’s Ferry) were due to major forces sticking to a fixed position and led by at best mediocrities.

Grant’s victories at Shiloh, Fort Donelson, and Chattanooga had very much to due with the actions of subordinates. It does not mean that Grant played no part, only that some of his mistakes, such as being surprised at Shiloh, were made up for by the men and their officers at the front.”

Then I stopped. I could answer each point but life is going by and to you, Grant is a hero, and making him a hero is good for the county, history, and our understanding of the war. To me he is a flawed man who had some successes and some failures. Grant is a fascinating man, in some ways as impenetrable as Lee.

We are doing to Grant what the Lost Cause did to Lee. We are making excuses for his failures, inflating his victories and skills, and making him a symbol. I long for the day when this edifice is destroyed. I despise historical idolatry and hero-worship.

Mr. Foskett: “He also outmaneuvered Lee more than once in the Overland Campaign by flanking to Lee’s right.” And that had no relation to the fact Union forces outnumbered Confederate forces 2 to 1? (i.e., “superior numbers”)

Mr. Williams: Two brief points. (1) By definition, maneuver and outflanking an opponent do not involve the use of brute force with overwhelming numbers; (2) I strongly recommend Alfred C. Young’s 2013 book on Lee’s numbers in this campaign, in contrast to the mythology cooked up by Early, et al. Gordon Rhea put it well – Grant caught Lee wit his pants down at least once during this campaign. And, again, my point is not to salute Grant as a preeminent tactician (an area in which he had his shortcomings). It’s to refute the Lost Cause stereotype that he only defeated Lee because he had more men and resources.

Mr. Foskett – Points well taken, but I maintain that an average general can do wonders with superior numbers and supplies. I’m not suggesting that Grant was not a good general. But I’ve never heard anyone argue (successfully) that attrition was not a significant factor in the Union’s (and Grant’s) advantage. Superior resources (in sheer volume) and make just about anyone look great. Again, we’ll have to agree to disagree.

“can make”

The only reason to believe Lee was NOT a hero were his political views prior to 1861, which were not unusual or remarkable. 90% of well-to-do Southerners thought secession was a constitutional right and 90% of America were NOT abolitionists.

Lee was not a fire-eater and opposed secession. When VA left the Union, he went with it. He wasn’t fighting for slavery but for Confederate Independence. After the War, he did everything he could – publicly – to bind up the nations wounds and get his fellow Southerners to reconcile themselves to the new situation.

If people want to admire Generals based on their politics, maybe Ben Butler or Pope is more thier style.