Deconstructing Meade’s Decision at Mine Run

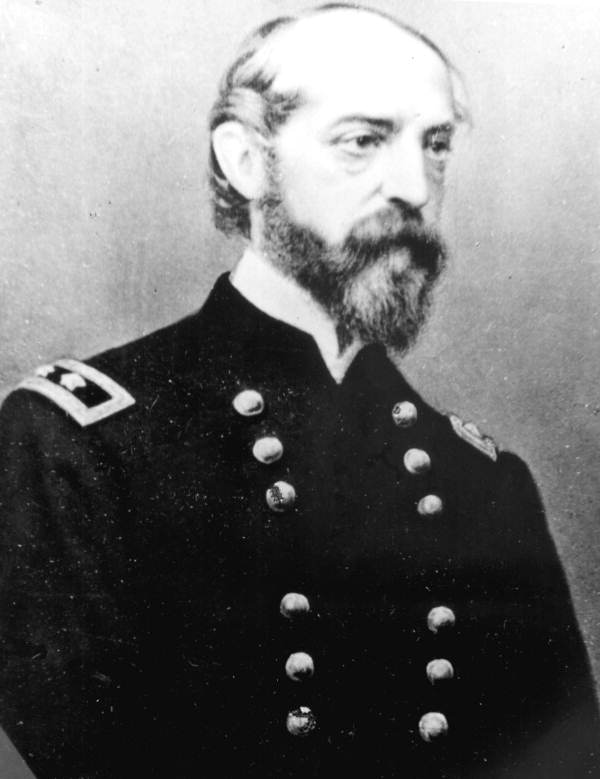

On the morning of November 30, 1863, Gouverneur K. Warren awoke to a surprise. The evening before, he had positioned nearly half of the Army of the Potomac on the far Confederate right, poised for an attack at 8:00 the next morning. To meet the threat, Confederates, under the cover of darkness, extended their line and fortified. When Warren saw the result of their efforts, he balked. “The full light of the sun shows me that I cannot succeed,” he later said.

The evening before, Warren had assured his commander, George Gordon Meade, that the attack would succeed, so when Warren sent word to Meade that he was calling off the assault, Meade nearly exploded. “My God! General Warren has half my army at his disposal!” he shouted.

A quick ride by horseback to Warren’s front, followed by a 15-minute inspection of the Confederate line, revealed an indomitable-looking Confederate position. Meade, reluctantly, agreed with Warren’s assessment. “If I had thought there was any reasonable degree of probability of success, I would have attacked,” Meade later explained to his wife. “I did not think so; on the contrary, believed it would result in a useless and criminal slaughter of brave men, and might result in serious disaster to the army.”

Meade lamented that Warren “ruined me” with the decision, although Meade himself ended up backing that decision.

Was it the right call?

Through the lens of hindsight, we know that Warren’s decision forebode a similar pattern of behavior in the Overland Campaign. Meade would often issue orders to Warren that Warren treated as discretionary instead of preemptory. Warren often felt his judgment was better than his superiors’ and that his view on the ground superseded the more strategic view of his commanders.

We also know that Warren preferred to be overprepared for his attacks rather than strike merely because opportunity presented itself. As an engineer, Warren liked to have his i’s dotted and t’s crossed, and anything less meant less-than-optimal circumstances for attack.

That hindsight makes it tempting to think Warren overreacted to the appearance of Confederates in his front. Perhaps Meade should have attacked after all. Meade knew his critics would certainly think so. “I am fully aware it will be said I did wrong in deciding this question by reasoning,” he told his wife, “and that I ought to have tried, and then a failure would have been evidence of my good judgment; but I trust I have too much reputation as a general to be obliged to encounter certain defeat, in order to prove that victory was not possible.”

It’s worth remembering that Meade did not have the benefit of our hindsight. Instead, he relied on Warren because he had good reason to. After all, Warren’s keen eye had averted disaster on Little Round Top at Gettysburg. His performance leading the II Corps during the subsequent months had gone smoothly, highlighted by his effective repulse of Confederate attacks at Bristoe Station in mid-October.

Warren was, in late November, a star still very much on the rise.

It’s also worth noting that Confederates had never before thrown up field fortifications in the midst of battle to meet a Federal attack. The works at Mine Run were a new innovation. That must’ve been puzzling to see, especially to Warren, whose engineer’s eye would’ve looked on such works critically. Meade, too, was an engineer, so he likewise would’ve inspected the fortifications with the eye of an expert.

Hindsight lets us look at Warren’s behavior as a precursor to further trouble, but in the moment, he made the best call he could, and Meade had plenty of reason to trust him.

I am sympathetic to Warren during the Overland Campaign. At Wilderness and Spotsylvania he was ordered to make attacks he knew would fail and they did. Grant and Meade should have listened to him. By the time he gets to Petersburg, his morale has cracked and he became lethargic on June 17, with disastrous consequences for the fighting that day.

Warren is a bit of a tragic figure, his real talents worn down by both personality flaws and the war he found himself fighting in 1864.

Good post by the way. I cannot “like” posts on here for some reason having to do with WordPress saying my account does not exist whenever I try to like a post.

Get in touch with WordPress one-to-one. They solved a couple of my issues within a short amount of time & were very helpful and kind. It was worth the effort–who knows what glitches lurk within the Internets!

Question: approximately where were Warren and Meade position wise to observe the Confederate works at Mine Run? Is the location accessible? Is there anything left of those foremedable works on the Confederate right?