Primary Sources: Longing To Be A Soldier

“I wrote Mother about my trip, but I don’t think I told her that most of our marches could be called forced marches, as we were on light rations half the time. I stood the Campaign “bully,” but felt as if I would never get enough to eat when I got back. Champe [sister’s nickname] tell Mother I have come to the conclusion that I had better get me an overcoat at once for every thing is going up daily. Saylor is going to write for the cloth for me and it will cost $10 or $12 per yard and it will take 8 yards then the lining will cost right much. Then I borrowed $20 to pay for a pair of shoes. So I want her to send me $150. I am out of money now, and would not object to having a little to buy pies, Cakes, Cider, &ct. occasionally. I also want to have a pair of gloves made….”[i]

“I wrote Mother about my trip, but I don’t think I told her that most of our marches could be called forced marches, as we were on light rations half the time. I stood the Campaign “bully,” but felt as if I would never get enough to eat when I got back. Champe [sister’s nickname] tell Mother I have come to the conclusion that I had better get me an overcoat at once for every thing is going up daily. Saylor is going to write for the cloth for me and it will cost $10 or $12 per yard and it will take 8 yards then the lining will cost right much. Then I borrowed $20 to pay for a pair of shoes. So I want her to send me $150. I am out of money now, and would not object to having a little to buy pies, Cakes, Cider, &ct. occasionally. I also want to have a pair of gloves made….”[i]

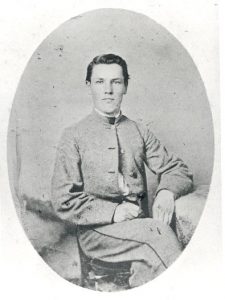

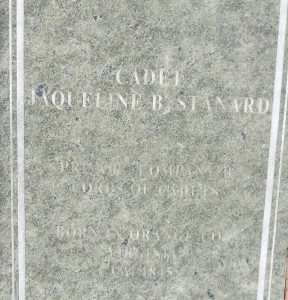

The collection of letters by Cadet Jaqueline Beverly Stanard offer a glimpse into boyhood, cadet life at Virginia Military Institute, and homefront life during the Civil War. Published in 1961 by the University of North Carolina Press under the title Letters of a New Market Cadet, the bound and annotated version includes his letters to his mother and sisters, along with several class essays.

Stanard – called “Jack” by his classmates and “Bev” by his family – matriculated at Virginia Military Institute in January 1863. Sent to this rigid school, Stanard spent much of the next seventeen months letting his mother know how much he wanted to be a real soldier and writing stories and scenes to evoke her mercy and pity on his “hard life.” Mrs. Stanard, a widow, thought she had calculated to keep her youngest son out of the war by sending him to military school and did not yield to his pleas to resign and join up or get a position on some general’s staff.

Information in the letters tends to be scattered, written as Stanard thought of the news or his rather numerous requests. However, his missives give readers a valuable glimpse into the 1863 and early 1864 life of VMI Cadets, including details about classes, sports and other interactions with classmates, campaign marching in the winter as reserves to help counter a Union cavalry raid. Homefront glimpses also appear in the letters as Stanard teased his sister and reported on the doings of the young ladies in Lexington, Virginia – including a certain Miss Pendleton who seems to have been his secret crush. Mixed in with those details and a fair portion of manly complaining, a look at a young man’s youthful wants and pastimes also emerges. Iceskating, fishing, tormenting a groundhog, playing jokes on friends, flirting a little with the girls, borrowing money, and the constantly hunting for food to assuage teenage hunger offer a chance into the life and pleasures of a healthy, activity young man who was not in an army.

At the very beginning of my studies on the Battle of New Market and the role of the VMI Cadets, I picked up the published volume of Jack’s letters. Doubting their helpfulness since I already knew he did not write about the battle itself, I still determined to give the letters a chance. I had time on my hands that winter and decided to read each letter and essay out loud. That became an unforgettable experience!

It is one thing read primary sources, study and enjoy them. It’s another to read them out loud. Once I stopped grimacing at some of the wording and grammar, I found myself getting a better sense of this individual’s hopes, dreams, and everyday problems. Reading the letters out loud helped me gain an appreciation for his writer’s voice and study that more closely.

Some secondary sources cast Jack Standard as “mama’s boy” or an overly needy cadet. I can see why that conclusion might be drawn. However, these surviving letters were private and to his mother (or sisters); the neediness and softer side that appears in the letters should not necessarily equate those same characteristics into the character his comrades knew and saw. Everyone writes and behaves different toward those who know them best. Enough bragging, stories, and hints at escapes comes through the letters to Mother to suggest that Standard had his full share of adventures and could keep up with the most ambitious of the cadets to rack up demerits.

For those who know the history from the Battle of New Market and the names of the ten cadets who did not return from the battle, this letter collection will be bittersweet to read. Jack Stanard did not survive the fight, dying of a gushing leg wound. This adds a sense of tragedy and grim irony to many of his letters, but readers must remember that he did not see his writings that way.

The following excerpt comes from the beginning of an uncorrected, drafted essay entitled “War” by Cadet Stanard:

Of all the punishments which Divine Providence sees fit to inflict upon a sinful nation, none are so terrible, none so severe as that of war, which is now being so frightfully carried on throughout this once peaceful and prosperous republic…[ii]

On May 12, 1864, the Corps of Cadets arrived in Staunton, Virginia after accomplishing an approximate fifty mile march in two days. Jack snuck out of camp with some friends to spend the evening at their home in the town. While there, he stepped out of the parlor and wrote his mother a two page, crosswritten letter. Part of it reads:

We will leave in the morning early and expect to have a march to Harrisonburg (down the Valley) a distance of 26 miles. The Yankees are reported coming up the Valley with a force of 9000 strong. Our Corps [of Cadets] will run Gen. B. up to 5000 may be more. I hope we may be able to lick them out. I have suffered more with my feet this march (so far) than I ever did on all the others together. I hope to get me a more comfortable pair of shoes when this will be remedied. I got my trunk the evening before I left all safe. It was in the nick of time and my biscuit and ham for the rations. If you want to write to me direct your letter to me at this place Care of Edmond M Taylor, Staunton, he will send them to me. I expect we will be down out this time for some weeks. I told you that you had better let me join Lee at once that this could be the way, but you must not make yourself uneasy about me. I will take care of myself. One of my messmates from this place is going to fill my haversack with something better than what we draw so I wont suffer for some days at any rate, though I hope not at all. Well darling Mother I have written enough I suppose to relieve your mind as to our destination so I must stop and go in the parlor. Some young ladies there….[iii]

As I read aloud the words, I struggled with the knowledge of how his life ended. On a battlefield, as a soldier – in the kind of military venture he had always wanted to experience. Except he did not live to see the end of the fight or the legacy that followed. Sometimes, it was hard to read his letters and his endless begging to go to war, knowing what really happened to him when the cadets were called out in the spring of 1864.

These published letters and essays offer a rare to chance to get to know a teenage cadet through his own words, to glimpse his life the way he saw it. Many VMI Cadets who survived New Market wrote about their school days and battle experience, but with the advantage of hindsight. The survivors could remember themselves in certain ways. Jack Stanard did not live to write his own memory, but his own unpolished words still ensured his voice in the New Market and VMI history. Jack Stanard – a young man who longed to be a soldier – left a written record of highlights of his life in the final months before his dreams exploded into wrenching reality at the Battle of New Market in the spring of 1864.

Sources:

[i] Stanard, B., edited by J.G. Barrett and R.K. Turner, Jr. Letters of a New Market Cadet, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1961. Letter: November 15,1863, (pages 13-14)

[ii] Ibid, “War” essay (page 38)

[iii] Ibid, Letter: May 12, 1864, (pages 61-62)

Sarah Kay, I’m confused. As I followed up on Jack Standard and his death at New Market, I reviewed “”Put the Boys In…,” only to discover that M/G David Hunter is reported therein to have “met his demise at Lynchburg a week later.” I believe Hunter died in 1886, long since retired from the Union Army and an active role in the trial of Lincoln’s assassination conspirators. HELP!