Going Courting in Lexington, Virginia – Part 1

Theology and Presbyterian doctrine. That’s what first took Major Thomas J. Jackson to the home of Dr. George Junkin in Lexington, Virginia. But before long, theology and doctrine wasn’t the only thing on the major’s mind. Dr. Junkin’s daughter, Elinor, lived at home, eligible and unmarried. Whether he admitted it or not, “Old Jack” was going courting.

What did courtship and the path from acquaintanceship to marriage look like in mid-19th Century America? How did men and women “go courting” in Lexington, Virginia? In honor of Valentine’s Day, let’s take another look at love from a historic perspective – both in theory and practical life in a real town where real men and women fell in love, got married, or suffered broken hearts.

Unlike previous generations where marriages were contracted more for material gain and social standing than romantic love, the mid-19th Century saw a revival of the ideals of romance. Aided by popular literature and counseled by parents and religious tracts, love and practically interwove in the culture of courtship and matrimony. Ellen K. Rothman described it this way in her study Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America: “The vision of romantic love that prevailed in the mid-1800s stressed mutuality, commonality, and sympathy between man and woman – precisely those qualities most likely to bridge the widening gap between home and world.”[i]

In letters and journals from the Civil War era, engaged couples frequently traced their relationship through a strong stage of friendship and testing of their common interests and beliefs. Labeling stages of romantic relationships can get messy since none follow one set cookie-cutter plan of falling in love. However, it’s safe to generally outline acquaintance, friendship, courtship, engagement, marriage as the typical pattern found during the Civil War era. Sometimes, this took just a few days or weeks; for other couples, it might take years.

The 1850’s and 1860’s in Lexington, Virginia, offer glimpses into what this pattern looked like in a rather strict community. Unlike a fashionable city with concerts, opera, and dances, Lexington society approached life more soberly, more realistically – giving a better idea of what “dating” or courtship looked like in small town America. Young men studying at Washington College or Virginia Military Institute (VMI) had their share of crushes and flirtations, some serious, some entertaining and harmless feelings of the moment. Older single folks found love too in Lexington.

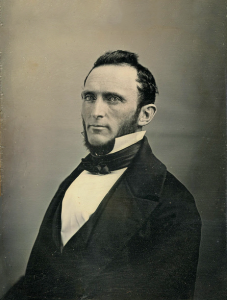

Major Thomas J. Jackson, a bachelor and twenty-eight years old, navigated his way through Lexington society. Teaching at VMI, actively pursuing his religious beliefs, and taking part in literary entertainments, Jackson walked the streets of Lexington, looking very eligible – if a lady could love or tolerate his eccentricities. He was not bad looking, either, and had a solid military record from the Mexican-American War. Looking at an image of the major, it’s not hard to see why Miss Ellie Junkin fell for him, wanted to help him adapt to civilian life, and shared his religious vision.

Miss Elinor Junkin – an “old maid” at twenty-seven – had seemed to contentedly resign herself to living her days keeping house for her parents and being a devoted companion to her sister, Margaret. The Junkins had moved to Lexington in 1848 when Dr. Junkin became president of Washington College. Older than most of the students in town, perhaps Elinor doubted she’d find love – her sister certainly did. Then, VMI got a new professor and the Presbyterian church got a new and devout member.

The details of Miss Elinor and Major Jackson’s courtship are hazy. Their acquaintance began through church and the major’s visits to talk with Dr. Junkin. Then Elinor and Thomas started talking and found they had a lot in common. Still, it’s curious to wonder what Jackson told Elinor because, according to Margaret Junkin, he didn’t tell the family about his war record until well after the engagement. We don’t have the details of exactly when or how Jackson proposed, but by early 1853, the couple announced their engagement.

Months later on August 4, 1853, Major and Mrs. Jackson were married and headed north on their “wedding tour” before settling into blissful married life in Lexington. The Jacksons’ happiness seemed complete when Elinor knew she was pregnant. However, on October 29, 1854, Elinor Junkin Jackson died from complications of childbirth and her little one did not survive either.

Sorrow pulled Jackson and his sister-in-law, Margaret, closer. Eventually, their correspondence turned from grieving to gently teasing, and the two became much better acquainted. Observers might have said they were courting from the ease of their conversation and close friendship. However, both Major Jackson and Miss Margaret held to a tenant of their Presbyterian faith which at that time forbade marriage to a deceased wife’s sister. The two remained close friends but were not romantically attached.

Instead, Miss Margaret Junkin had a surprise. John Thomas Lewis Preston – professor of Latin and English at VMI, good member of the Presbyterian church, and a friend of Major Jackson – came calling. Miss Junkin had known the Preston family for a while before the tragedy struck in 1856: Mrs. Sally Preston died, leaving seven children. John Preston sent his children to live with relatives until he could find a way to bring the family back together. Margaret Junkin – in her later thirties, unmarried, fond of children, and well-educated – seemed like a possible step-mother and new wife. However, unlike other courtships in Lexington, this one did not progress peacefully. Margaret was a published authoress; John did not like that her name appeared in print. Both had tempers, and the stormy tantrum flares nearly cancelled the wedding.

In the end, Mr. and Mrs. Preston were married on August 3, 1857, and suddenly the lonely authoress who had wanted a home and family of her own had children to look after, a three story house to manage, and the decision to set aside her public writing career. For Mr. and Mrs. John Preston, their courtship stemmed from necessity and respect. That’s not to suggest they did not love each other, but unlike younger couples, they had to find a way to bring a family of children back together and make sacrifices to convention and ideals.

While the Jacksons and Prestons serve as examples of older, wiser couples approaching courtship and matrimony intentionally, younger men and women in Lexington indulged in much less serious and mostly harmless flirtations. Usually this took the form of gatherings of young people – typically in homes or at charity events.

During the Civil War years, VMI Cadet J.B. Stanard revealed his feelings for Miss Hughella Pendleton in letters to his mother and sisters. He spied on her regularly in town when she went ice-skating and attended a “tableaux…last Friday night by the ladies for the benefit of the poor soldiers.”[ii] Stanard reported that Miss Pendleton did not seem very popular, but whether he meant that as criticism or a hopeful note that she wasn’t seeing someone else remains unclear. Then in January, he reveals that Miss Pendleton had a beau, reporting without comment. A couple weeks later, Stanard calls her his “friend” and remarks on her pretty appearance when they went ice-skating.

Their relationship – if it even was a relationship – ended as friends. Miss Pendleton was not mentioned again in his letter collection, leaving researchers to wonder if she ever knew that “Jack” Stanard liked her or if he just had an infatuation that he kept to himself and his private correspondence. Certainly, Cadet Stanard had reason to keep his feelings quiet. Other boys had numerous pranks played upon them by their buddies who knew about their crushes or love interests.

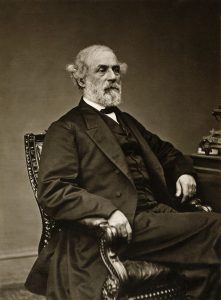

VMI wasn’t the only school in town with young men in need of a hospitable welcome from the citizens and young women. Washington College boasted a fine group of students, and after the Civil War, the arrival of former General Robert E. Lee boosted the school’s renown. With Lee came his daughters, all unmarried. Miss Agnes and Miss Mary pushed the boundaries of conservative Lexington society by going on a sleigh ride with VMI officers and staying out until 8 p.m., then starting a Reading Club for both young women and men! Finally, the young Lees managed the unthinkable: they organized a dance at VMI that lasted until 3 a.m. Out of deference to the community, only reels, lancers, and quadrilles were danced, since they feared introducing “round dancing” (waltz, polka, etc.) would have landed them all in wrathful unappeaseable judgement from the strict Presbyterian town.

When the young men came calling at the Lee Home in the evenings, the girls could entertain in the parlor, under the kind, watchful eye of their parents. The General and Mrs. Lee sat in the dining room, reading newspapers and mending while the younger generation talked, flirted, discussed, or sang in the parlor. Although he didn’t seem to mind the modernization his girls brought to Lexington visiting and courting, Lee had his rules. Ten o’clock curfew at the Lee House. When the hour came, the former general came from the dining room to “close the shutters carefully and slowly, and, if that hint was not taken, he would simply say, ‘Good night, young gentlemen.’”[iii]

Ideas of romantic love, marrying for affection, and finding a compatible partner for life reigned in the courtships of 19th Century America and was exemplified in Lexington’s serious romances. Unlike other places where swift flirtations were the rule of the younger generation, Lexington tended to keep its cadets, students, and girls within its strict rules which stemmed from religious principle. Still, the young folk fell in and out of teenage love, got teased, and simply enjoyed the company of other young people for a variety of “uncorrupting” activities.

Though each individual and couple had different experiences, the generalizations about courtship connected to their era and town held true in the lives of Major and Mrs. Jackson and Mr. and Mrs. Preston. It remains unclear if Cadet Stanard and Miss Pendleton were ever courting or simply good friends and how serious the Lee girls might have been about any of their college student acquaintances. Still, their experiences provide valuable insight to the culture and stages of life in Civil War America.

Then as now, love is a journey influenced and shaped by traditions, beliefs, and individual personalities. Whether it’s called dating or courting, there is still the law of attraction, creation of a unique friendship, and – perhaps eventually – the decision to build a life together. Sometimes, it all starts when the new professor in town wants to talk about theology with father…or something as unexpected as that!

To be continued later today with a primary source excerpt about going courting in Lexington…

Sources:

[i] Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1987. (page 107)

Klein, Stacey J. Margaret Junkin Preston: Poet of the Confederacy, A Literary Life. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, South Carolina, 2007.

[ii] Stanard, B., edited by J.G. Barrett and R.K. Turner, Jr. Letters of a New Market Cadet, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1961. (page 18)

[iii] Zimmer, Anne C. The Robert E Lee Family Cooking and Housekeeping Book. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1997. (page 47)

This is charming. What a nice read for Valentine’s Day.