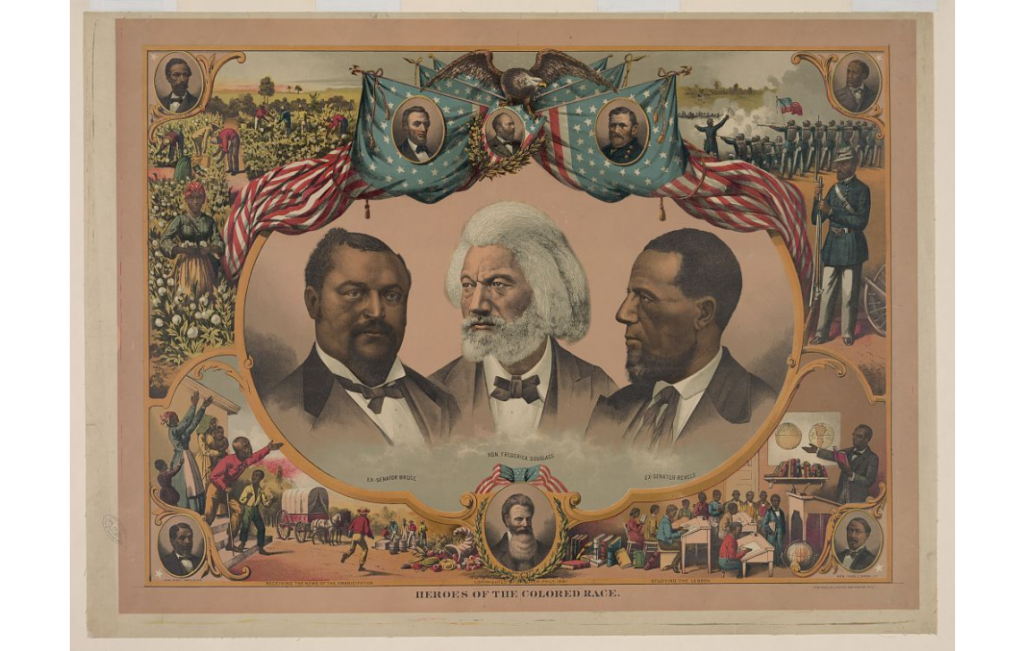

Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce: America’s First Black Senators

On February 25, 1870, visitors in the U.S. Senate gallery burst into applause when the new Republican senator from Mississippi entered the chamber. This man was no ordinary senator. He was Hiram R. Revels, and he was the first African American ever to sit in either house of Congress. Under the laws of Reconstruction, Mississippi had just been readmitted to the Union two days before, and the state legislature, dominated by carpetbagger Republicans, immediately voted to send Revels to the Senate.

On February 25, 1870, visitors in the U.S. Senate gallery burst into applause when the new Republican senator from Mississippi entered the chamber. This man was no ordinary senator. He was Hiram R. Revels, and he was the first African American ever to sit in either house of Congress. Under the laws of Reconstruction, Mississippi had just been readmitted to the Union two days before, and the state legislature, dominated by carpetbagger Republicans, immediately voted to send Revels to the Senate.

The seat Revels filled had last been occupied by Senator Albert G. Brown, who resigned when Mississippi declared itself seceded from the Union in early 1861. Shortly before the state seceded, Brown had declared that “Things have reached a crisis. The crisis can only be met in one way effectually, in my judgment; and that is, for the northern people to review and reverse their whole policy upon the subject of slavery.” One wonders what Brown, who served as a Confederate Senator from Mississippi during the Civil War, must have thought about his old seat being occupied by a black Republican.

Hiram Rhodes Revels was born in North Carolina on September 27, 1827. He was born to free black parents and was a free man his entire life. He attended Union County Quaker Seminary in Indiana and Darke Seminary in Ohio before being ordained as a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1845. He traveled throughout the Midwest to preach and teach religion and remembered that “At times, I met with a great deal of opposition. I was imprisoned in Missouri in 1854 for preaching the gospel to Negroes, though I was never subjected to violence.” He later attended religion classes at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, which would host one of the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858.

When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation at the beginning of 1863 and black men were permitted to serve in Union military forces, Revels set to work recruiting and organizing units of the U.S. Colored Troops. He went into battle with them as a chaplain at Vicksburg and other western theater engagements.

After the war, Revels became a minister at a Methodist church in Natchez, Mississippi and was elected to the state senate in 1869. When Mississippi was readmitted to the Union in early 1870, Revels, a black man and a Republican, seemed the perfect person to send to the U.S. Senate. Southern Democrats naturally opposed the Mississippi legislature’s appointment of Revels, claiming that no African American had been a U.S. citizen before the Fourteenth Amendment and that Revels therefore did not meet the requirement of being a citizen for nine years before election to the Senate. Supporters rejected this argument, and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, a longtime abolitionist before the war, said, “The time has passed for argument. Nothing more need be said. For a long time it has been clear that colored persons must be senators.” The Senate voted 48 to 8 to seat Revels.

During his time in office, Revels worked for legal equality and physical protection for the freed men and women of Mississippi. The northern press praised his oratorical abilities, and his hard work and that of other African Americans who later served in Congress led white Senator, Secretary of State, and presidential candidate James G. Blaine to note in his memoirs that “The colored men who took their seats in both Senate and House were as a rule studious, earnest, ambitious men, whose public conduct would be honorable to any race.”

Revels’ term expired in 1871 and he became the president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University) in Mississippi. He retired in 1882 and lived until January 16, 1901. His remains are interred in Hillcrest Cemetery in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Ironically and fittingly for a black man who fought most of his adult life for racial equality, his grave lies not far from those of five Confederate generals.

Hiram Revels was the first African American to serve in Congress, but he did not serve a full six-year Senate term. That distinction fell to Blanch Kelso Bruce, who represented the same state—Mississippi—in the Senate from 1875 to 1881.

Unlike Revels, Bruce, a native of Virginia, was born into slavery. Bruce’s natural father was Pettis Perkinson, the white man that owned Bruce’s mother Polly. Perkinson treated the young Blanche Bruce fairly well, even allowing the young man to be educated to read and write and to play with his white half-siblings. Perkinson eventually freed Bruce and even arranged for him to learn a trade and work for wages.

Bruce became a teacher and for two years attended Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, one of the nation’s most racially progressive communities and a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment before the Civil War. During the war, Bruce made his way to Kansas, where he unsuccessfully tried to enlist in the Union army. In 1864, he moved to Missouri, establishing and running a school for black children in Hannibal before moving to Mississippi in 1868.

Bruce became a wealthy landowner in his new home state, eventually owning thousands of acres near the town of Cleveland in northwestern Mississippi. He served in a number of civil positions and was elected sheriff of Bolivar County. Bruce also worked in Mississippi as a registrar of voters, tax assessor and collector, supervisor of education, and editor of a local newspaper. In 1870—the year Mississippi was re-admitted to the Union and Hiram Revels was sent to the U.S. Senate—Bruce became sergeant-at-arms of the Mississippi State Senate. In 1872 he was named to the board of levee commissioners for a three-county district. These commissioners worked to raise money to build embankments in the Mississippi Delta region.

By the mid-1870s, Blanche Bruce was Mississippi’s best-known African American political figure. In 1873, Bruce was offered the state’s lieutenant governorship, but he had his eye on a larger prize: a U.S. Senate seat. Former Radical Republican state governor Adelbert Ames, a West Point graduate and decorated Union Civil War veteran, was leaving his spot in the U.S. Senate in early 1874 and returning to Mississippi for another term as governor. In January, the state legislature nominated Bruce not to serve the remainder of Ames’s term, but to serve a full six-year term in the Senate from 1875 to 1881. The full state legislature voted on February 4, 1874 and nearly unanimously elected Bruce to the full term. When Bruce arrived in the Senate on March 5, 1875, courtesy and precedent called for the state’s senior senator to escort Bruce, the new junior senator, up to the aisle and to the podium to be sworn in. But Senator James Alcorn, a moderate Republican and former Confederate officer (despite being born in Illinois), refused to escort Bruce. Instead, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York walked up the aisle with Bruce, and this began a long friendship and political alliance between Bruce and Conkling.

Like Revels before him, Bruce worked diligently in the Senate to support freed men and women in Mississippi. In 1878 he tried to pass legislation to desegregate the U.S. Army and two years later demanded an investigation into the brutal hazing of black West Point cadet Johnson Whittaker. He supported black colleges and opposed legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act that sought to discriminate against other minority groups. On February 14, 1879, Bruce briefly presided over the Senate, making him the first African American ever to do so. The following year, 1880, he unexpectedly received eight votes for vice president at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, making him the first African American to receive votes for national office at a major party convention.

Blanche Bruce did not attempt to win a second Senate term in 1880. With Reconstruction all but over in Mississippi, voters had recently turned the state legislature back over to the Democratic Party, and Bruce knew that, despite his relative moderation on many issues, white Democrats would not accept him for another term. When Republican and Union Civil War veteran James A. Garfield became president in early 1881, he appointed Bruce as Register of the U.S. Treasury. In this position, Bruce became the first black man to have his signature appear on U.S. currency. Bruce stayed in this positon until 1885 and was then the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia (a job once held by Frederick Douglass) from 1890-93. Bruce was briefly Register of the Treasury a second time in 1897-98 under President William McKinley, another Republican and the last Civil War veteran to serve as president.

Blanche K. Bruce died at age 57 on March 17, 1898, just three months into his second stint at the Treasury Department. His wife, Josephine Beal Willson Bruce—a women’s rights activist and the first African American teacher in the public school system of Cleveland, Ohio—outlived him by twenty-five years, surviving until 1923. The Bruces are interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

The lives, careers, and public services of both Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce were honorable and important. They remind us of the appropriateness of making the Civil War about more than just saving the Union, but making it better by creating the “new birth of freedom” for all of which Abraham Lincoln spoke. Revels, Bruce, and millions of other African Americans before and since are integral parts of our nation’s history whose stories should be understood and appreciated not just in February, but every day of the year.

Thank you so much for this. I have always been intereted in the African-American politicians elected after the war.