Albert Sidney Johnston Stumped at Shiloh

Imagine your job is to go around an unmarked battlefield and mark the places where significant events happened. Yes, you were there at the time of the fight, but of course, things were a bit confusing at the time and you were pretty stressed out. The field looked different then, too, and, of course, there was a lot of battle smoke.

That would be challenging enough, I imagine. But also imagine if you were seventy-eight years old—not the nimblest condition for battlefielding, certainly, although not impossible. And imagine that it had been thirty-four years since you were in the middle of that chaotic fight.

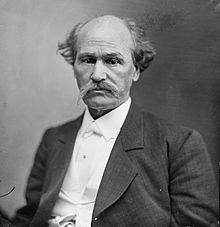

Such was the case for United States Senator Isham G. Harris, who revisited the Shiloh battlefield in 1896—just a year before his death, although he could not have known it at the time—to track down the location where Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston had been mortally wounded on April 6, 1862.

In that early spring of the war, the 44-year-old Harris had been governor of Tennessee. Nashville had fallen a month and a half earlier and, by the start of April, remained under Federal occupation. That left the Tennessee governor in a kind of exile. To make himself useful in the effort to recapture his state capital, he volunteered his services as an aide on Johnston’s staff.

During the first day of battle, as the Confederate advance bogged down around the Hornet’s Nest, Harris ran messages for Johnston. At one point, Johnston sent him with a message to Col. Winfield S. Statham’s Brigade; when Harris returned, he found Johnston swooning in his saddled. Harris and another staffer, Captain W. L. Wickham, supported their commander in his saddle as the general admitted he’d been wounded—“and I fear seriously,” he said.

The small party moved their horses down into a nearby ravine to get out of the line of fire. They eased Johnston from his horse and, leaning him against a tree that was, itself, leaning, they discovered a wound on his right thigh, just above the top of his boot. A bullet had clipped his femoral artery. Johnston died within minutes of blood loss.

The ravine is as bucolic a spot as one might hope for as a place to pass away. Even in early April, when the trees have yet to burst into their full green, the spot is quiet and beautiful. In full summer, the leaves muffle any sound of traffic from the nearby park road, creating a pocket of tranquility in the midst of an already-hushed battlefield protected by its isolation and preservation. The ravine is a lost world. Today, a sign there—written by Harris—tells the story of Johnston’s death.

When the former governor scouted out the area those thirty-plus years after Johnston’s death, one of the landmarks he looked for was “the large lone oak tree under which the General sat.”[1] It was there, he said, where he first found the swooning general.

Consider the scenario again: he’s not in the prime of his life, it’s been 34 years since the battle, things were really confusing at the time, the forest has since matured, the smoke has cleared, the fog of memory has thickened. Historian Tim Smith points out that they weren’t the happiest of memories for Harris, either. “To him, Shiloh was the epitome of loss and defeat,” Smith says.[2]

“The whole subject of Shiloh is a bitter memory which I do not allow myself to talk about or think about when I can help it,” Harris said during his visit, discouraging idle chit-chat about the battle. “I have never visited the field since the battle and would not now except at the urgent request of the friends of General Johnston.”[3]

Harris found the oak tree, which the park commission marked with a wood sign:

Harris found the oak tree, which the park commission marked with a wood sign:

Gen. A.S. Johnston

Mortally Wounded

2:00 p.m. April 6th 1862

Died in Ravine 50 yds South

But did Harris pick out the tree under which he found Johnston? Historians disagree. “It probably wasn’t here in 1862, and if it was it probably couldn’t have been more than a sapling,” park historian Stacy Allen told Tony Hortwitz in 1998.[4] Wiley Sword argued for an entirely different location altogether. Smith thinks “the evidence suggests it had [been there].”[5]

In some respects, though, the veracity of the tree’s identity became moot because the tree soon took on a life of its own in Shiloh memory. After Harris marked it, “the tree became the place most associated with Johnston’s death,” Smith says in a short but excellent examination of the Johnston tree in his essay “Oft-Repeated Campfire Stories: The Ten Greatest Myths of Shiloh.” “No matter that the original wooden board said that Johnston actually died in the ravine fifty yards to the south. No matter that the large monument states that the general dies in the ravine. Most visitors believe that Johnston died under that specific tree.”[6]

Over time, the oak tree became the most popular site on the Shiloh battlefield and the focus of pilgrimages for Johnston devotees and Lost Cause adherents. To protect it, the Park Service had to erect a wrought-iron fence around it.

Even after the tree died in the 1960s, its stump remained in place for decades. Rangers even tried to put a tin cap over its top to prevent rain from falling directly into the exposed upper surface in an effort to prolong its afterlife. Eventually, Mother Nature’s attacks on the stump left it leaning so precariously that the Park Service had to prop it up with halyards.

Even after the tree died in the 1960s, its stump remained in place for decades. Rangers even tried to put a tin cap over its top to prevent rain from falling directly into the exposed upper surface in an effort to prolong its afterlife. Eventually, Mother Nature’s attacks on the stump left it leaning so precariously that the Park Service had to prop it up with halyards.

Any time they tried to take it down, though, a great clamor arose among Johnston’s fans who claimed the Park Services was trying to remove an authentic relic of Shiloh. The tree not only witnessed the battle, they argued, but also Johnston’s death—even though Johnston died in the ravine nearby.

“The famous tree that is so closely associated with Johnston had relatively little to do with his wounding and death,” Smith said unequivocally.[7]

This fascination with a stump doesn’t surprise me at all, though. After all, those of us who know the battle of Spotyslvania Court House know of the 22-inch oak tree shot down by rifle fire. The stump of the tree was excavated soon after the battle and displayed at the Spotswood Hotel. When Sherman’s army marched through the area on its way north to the Grand Review, soldiers “kidnapped” the stump and took it with them to Washington, where it remains to this day on display at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History.

The Spotsy stump speaks volumes about the ferocity of the fighting and, to Civil War buffs, has become iconic. For many, the stump marking the area of Johnston’s death evoked similar sorts of emotions and reverence.

In 2001, Mother Nature did what the Park Service had not been able to do: Decrepit and rotted, the stump at Shiloh finally came down.

It was several years gone by the time I first visited the Shiloh battlefield in 2006, although I didn’t know it at the time. Because of Horwitz’s book, I knew of the stump and went looking for it—in vain. I initially thought I had somehow just missed it outright until a friendly bookstore employee told me the stump had come down a few years earlier. I admit, I was disappointed.

By now, an entire generation of battlefield visitors have gone to Shiloh and not seen the stump, but the old oak still has a place in Shiloh memory for long-time battlefielders.

As Allen told Horwitz, “Legends die hard.”

————

[1] quoted in Timothy B. Smith, The Untold Story of Shiloh: The Battle and the Battlefield (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 36.

[2] Timothy B. Smith, This Great Battlefield of Shiloh: History, Memory, and the Establishment of a Civil War National Military Park (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 60.

[3] Ibid, 61.

[4] quoted in Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Vintage, 1998), 181.

[5] Smith, The Untold Story of Shiloh, 36.

[6] Smith, The Untold Story of Shiloh, 35.

[7] Smith, 36.

Photo credits: Harris (wikipedia); stump images (NPS); mortuary monument (author)

Excellent post. I was just there this Saturday.

A couple of other points:

1. Shiloh was a bad memory for Harris not only for ASJ’s death, but because he lost a brother and a nephew there.

2. The photo caption is, I believe, incorrect. That’s a much later photo.

I would like to send a copy of a post card supposedly depicting the Johnston oak,I purchased in 1961at Shiloh. The back reads, in part: “This old tree, now dying, was a witness to the death, April 6 1862, of the Confederate commander, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston.”

I have a stereo type picture taken ca. 1900 (at the latest) of the ASJ death tree. Really sad looking and maybe 24 inches of height left. I am a major Luddite-so if someone can tell me how to post a picture of this picture I would be much obliged. I do not use Facebook etc. so it must be direct to this site from my downloads. God love ya! BTW. A portion of Isham Harris’s Sword, was found about 5 years ago just off the Hamburg Road.

I remember seeing what was left of the Johnston Oak when I was about 12 or 13. It was being held up by a metal ring and metal supports that went from the ground to the ring. At that age it captured my imagination and I tried to imagine the day of the fighting and the General leaning against the tree bleeding and dying after being struck in the thigh by a .58 caliber miniball. Shiloh was one of the more fascinating civil war battlefields that I visited and learned about over the years.