A Captured Letter from the Battle of Brandy Station

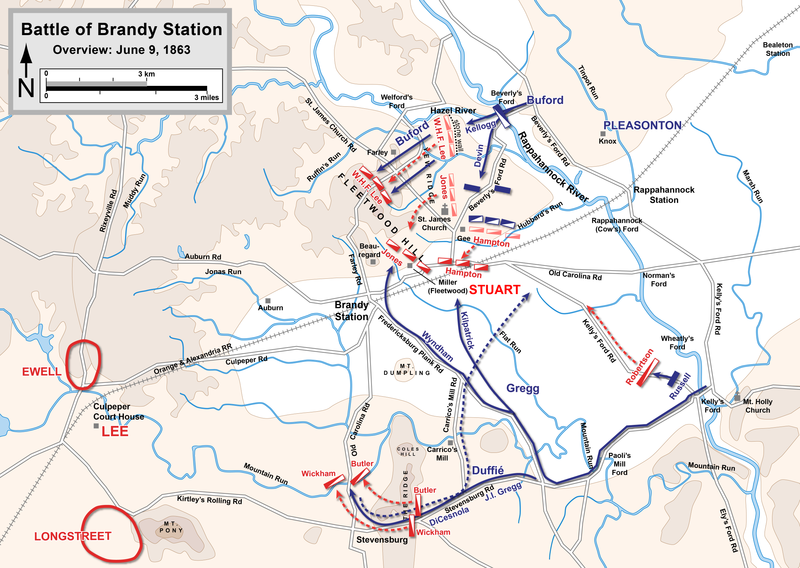

On June 9, 1863, one of the largest cavalry fights on the North American continent occurred. Known in the history books as the battle of Brandy Station, this conflict started when elements of Union General Alfred Pleasonton’s cavalry attacked Confederate General James E.B. Stuart’s camps and positions. Initially surprised, the Rebels rallied, formed, and fought back.

When the battle ended, the Confederates had regained the field, officially ending the fight in a draw. However, the Yankees had secured a morale victory, continuing to build their confidence and setting them up for further cavalry successes in the coming weeks and months.

Last year I sorted through some archival papers at The Huntington Library and turned through the files on the Battle of Brandy Station. Most were Union documents, but there was one file of “Confederate papers.” A handwritten note said that these two saved documents had been among the captured papers that General John Buford and his men found in the “enemy’s camp at Beverly’s Ford – on the 9th of June.” One of the papers was a set of orders concerning the cavalry review on June 8th. The other – a personal letter – caught my attention.

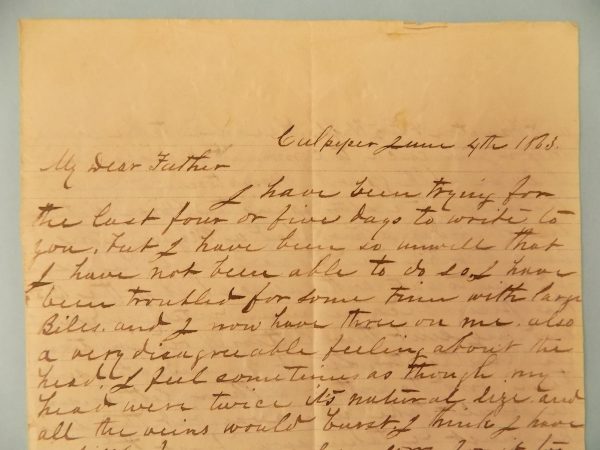

Written on June 4, without an envelope, and without even a last name for the author, the missive offers insight into the cavalry camp experience and rumors at the beginning of that month. Here is a transcription of the letter; I have done my best to ensure accuracy and when in doubt of a word have added a parenthesis either for interpretation or to acknowledge a set of hard to read lettering; spelling and punctuation is original.

Culpeper June 4th 1863

My Dear Father

I have been trying for the last four or five days to write to you. But I have been so unwell that I have not been able to do so. I have been troubled for some time with large Biles [boils?] and I now have three on me, also a very disagreeable feeling about the head. I feel sometimes as though my head were twice its natural size and all the [word] [brains?] would burst. I think I have a little fever now, I am sorry for it too for I think Stuart is preparing to make a raid into the enemies country, and when it comes, it will be something grand. For he has now about twelve thousand Cavalry at this point where he only had about four thousand before. his command has been augmented by Jones’ Brigade from the Valley & Robinson’s from North Carolina. We are to have a Review tomorrow of the whole force.

I think the Cavalry force here is to be re-organized. Stuart is to be made Lieut. Genl and Hampton & Fitz-Hugh Lee are to be made Major Genls each to command a division. if so, we will go with Hampton.

We had quite a stir[?] up in the Horse Artillery the other day. Stuart had a Major on his staff that he had no use for so he assigned him to duty with us as chief of the Batt[ery] The officers became immediately indignant[?] and they sent their letters of resignation in [word] [instantaneous?], Stuart immediately sent them word to withdraw their letters and he would take him away, but they said he must be taken away first. The consequence was that today he (the chief) sent over to [word] to Borrow a wagon to take his effects to [two words or abbreviations] – as he had been removed.

I got a letter from [name] yesterday she is at Greenville[?] and appears to be enjoying herself very much. She has commenced school. She says that mother is much better, and they speak of moving there next year to stay I think it a very good aragement.

There is nothing of interest to write about now. The weather is very fine. it invites a forward movement. The crops are all fine. Our horses are getting very fat. They have beautiful grazing fields. They are turned out all day, and then get some corn twice a day. I hear from the Boys pretty regularly. They speak of you as looking very badly, and say that the business you engage in does not suit you. I am extremely sorry to hear it, and am afraid you are braking yourself down.

Remember me to all friends and accept my best wishes from your son

Bill

Who was Bill? Did he survive the battle where his letter got captured? Was he even there or in a medical facility?

From the letter’s contents, we can deduce that Bill served in Stuart’s Horse Artillery. But without a last name, it’s sketchy to positively identify him at this point in my research. (If I do identify him through roster sheets as I’m studying Stuart’s Horse Artillery, you’ll be among the first to know!) I spent the week after finding the letter feeling sorry that I didn’t know more about this artilleryman, then I started to realize there might be a bigger lesson here: Bill’s letter itself.

He wrote it on June 4, 1863, and I don’t observe an inconsistency in penmanship that would make me think he wrote it in multiple sittings or over the course of multiple days. Then, probably in the busyness of getting ready for the Grand Cavalry Review on June 6th and 8th, he was not able to mail it. Or maybe Bill did “mail” the letter, but it never got farther than the post tent.

The letter got captured. Again, we don’t know the details. Was it with a stack of other letters? Was it in Bill’s tent or sleeping area? Did a “thievin’ Yankee” take it off Bill’s dead body? That’s right – at this point, I don’t know if Bill survived the battle or if he was even present.

Here’s what we do know and what the letter tells us. First, we find a shadowy glimpse of the semi-unknown writer: A sick soldier who still seems to be with his unit. A relatively well-informed man who kept track of camp rumors, promotions, unit squabbles, and the mood of the cavalry. An artilleryman who noted the foreboding promises of a coming ride into enemy territory. A horseman who kept track of the health and grazing of the horses that pulled the cannons and formed the cavalry troops. A brother and son who worried about his family.

Now, tucked and filed amongst folders and boxes of Union battle reports and correspondence, Bill’s letter tells its own story just by its existence and archival location. It reminds us of the early morning surprise at Beverly’s Ford when Buford’s Union boys charged hard into the Confederate camp, hoping to capture the horse artillery guns and render that formidable unit ineffective in the day’s showdown. But Rebel cavalry reacted, countercharging and fighting the Yankees (some rode bareback and jacketless attesting to their surprise and hurry). While the cavalry parried, sliced, thrust, and shot at close range, the crews of Stuart’s Horse Artillery raced to limber and gallop their guns away from the danger of getting captured.

Quite possibly in that dash and scramble, Bill’s letter either slipped from some storage place or remained behind. The letter to Father became an account and series of little stories never sent. At some point that morning, an enemy hand snatched the piece of paper. Maybe he read the words then or just stashed the letter for examination later. The Union officers were looking for information about Stuart’s plans in the opening campaign. Bill’s letter contains information about strong cavalry numbers, but it doesn’t really have further information that should have interested the Union commanders; still, somehow, the letter got preserved.

It never reached Father. But instead, its preservation – even with its limited information – offers a reminder and a perspective on the opening scenes of the Battle of Brandy Station. A scene of surprise and semi-panic where letters were left behind…to be captured, saved, and filed to haunt and remind historians of the personal side of war.

Source:

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. General Joseph Hooker Papers, Box 14, Folder M – Brandy Station.

Wow!! I throughly enjoyed this post and loved seeing the original letter. I’ve transcribed a few letters myself and they are always a fascinating look into the past. (And I believe he said he felt like his “veins” would burst. I also was wondering if he was suffering from “piles”, common for cavalrymen). Your vivid description of what might have happened left me feeling thrilled, sad and ultimately haunted as well. Thank you for making this lonely, obscure little letter come alive again!

Karen,

Thanks for taking a look at those mystery words. That certainly adds more information to his medical ailments. I appreciate the transcription help! Truly.

Sarah

Excellent find you made-! Very good article..

————————————————

[brains] would burst is actually veins

Biles is a term used during that time to mean a migraine.

So, one can see how the 2 terms tie-in.

Wish I could see the whole letter scan.

————————————————-

I also need to point out that the Battle of Trevilian Station on June 11-12, 1864 was the largest (& bloodiest) cavalry battle in North America. Brandy Station was the previous largest.

Good point, Dan. Thanks for pointing this out.

Brilliant! This is what I love about the Civil War community. Thanks for helping me decipher. I sometimes go “buggy-eyed” trying to figure out words. Maybe I should upload more of these lettering puzzles in the future? 🙂

Excellent article Sarah – I really enjoyed it, and what a find! Thanks for sharing it, too. I love stories like this!

Great article! There are still a lot of interesting letters and documents out there awaiting researchers like you. Keep up the good work!

Coddington cited to this letter in his book on the Gettysburg Campaign, and Bud Hall located it 30+ years ago. It’s an extremely useful and insightful letter. Thanks for focusing attention to it.