The Significance of June 19 in the Civil War Era—and Beyond

Amidst seemingly constant reminders that genuine equality for all in the United States remains elusive, it is worth remembering that today, June 19, has repeatedly been a momentous one for the cause of American freedom—particularly with regard to race. While many of the events that give June 19 its significance took place before or during the Civil War, just as many took place afterwards but serve to remind us of that era’s difficult and unfinished history.

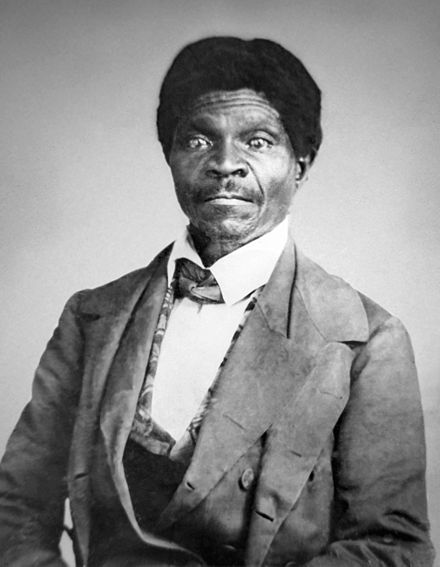

In the midst of the Civil War—when it seemed entirely possible the United States of America would fragment permanently and the Confederacy would succeed in creating a new nation based on racial slavery—President Abraham Lincoln took a dramatic step to remind his fellow citizens of what he believed was America’s true purpose. On June 19, 1862, Lincoln signed legislation prohibiting slavery in federal territories. This action effectively nullified the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, which held that African Americans could not be citizens, had no standing to bring suit in federal court, and were better off as slaves. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, a Marylander and slave owner, wrote of African Americans in his majority opinion:

“They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.”

This was the same logic that lay behind the construction of a Confederate nation based on white supremacy and racial slavery. The bill Lincoln signed 157 years ago rejected that version of government, and instead guaranteed freedom in the only place Congress could do so at the time: American territories.

This was no small thing. In the Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court had stated that Congress could not stop slave owners from carrying their human “property” into the West, where the U.S. government—charged by the Constitution with honoring the sanctity of private property—would have to protect it. This was a key factor in the coming of the Civil War, for it meant that slave owners could simply move west and any new states there would, by necessity, become slave states. Much of the vast land west of the Mississippi River would join the proslavery South, and those new slave states would dominate national politics. It was merely a matter of time until their votes in Congress outweighed those of the free states and, correspondingly, until slavery advocates forced free states to accept slavery, too. This was simply too much for northerners, and in late 1860 they elected the Republican Lincoln, who promised to stop the spread of slavery to the West. On June 19, 1862, he fulfilled that promise, using the federal government not to protect racial slavery, but to contain it where he had the legal authority to do so.

Three years after Lincoln ended slavery in U.S. territories, on June 19, 1865, enslaved African Americans in Texas officially learned of the Emancipation Proclamation—more than two years after it took effect. Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston to liberate Texas from the Confederacy and informed African Americans of the Civil War’s end—and their freedom. His General Orders Number 3 read:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages.”

Many African Americans have since celebrated June 19 as “Juneteenth,” a day of commemoration and remembrance of the abolition of slavery and a celebration of freedom in the United States.

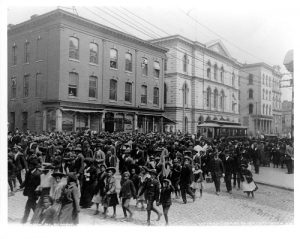

On June 19, 1945, approximately four million Americans turned out to cheer General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II, in a parade in New York City. Eisenhower was then the most popular man in the country, and both parties soon approached him to consider running for President in 1948. Eisenhower declined, though he did eventually run and win as a Republican in 1952 and again in 1956. Though Eisenhower’s predecessor, President Harry Truman, ordered the racial integration of the American military in 1948, much of the implementation and enforcement of that order was done by Eisenhower’s administration, including desegregating military bases, hospitals, and schools. President Eisenhower also sent the 101st Airborne into Little Rock, Arkansas in the fall of 1957 to forcefully integrate Little Rock Central High School in accordance with the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

On June 19, 1964, the United States Senate ended an 83-day filibuster on the Civil Rights Bill of 1964. That the bill was even necessary a century after the Civil War showed just how few promises of emancipation had come to fruition for African Americans. Senator Strom Thurmond, Democrat of South Carolina, led the charge against the bill, saying:

“This so-called Civil Rights Proposal, which the President has sent to Capitol Hill for enactment into law, is unconstitutional, unnecessary, unwise, and extends beyond the realm of reason. This is the worst civil-rights package ever presented to the Congress and is reminiscent of the Reconstruction proposals and actions of the radical Republican Congress.”

Other prominent Democrats that joined Thurmond in filibustering the bill included Senator Richard Russell of Georgia and Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia. On June 19, 1964, however, the bill’s manager, Democratic Minnesota Senator and future presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey, finally had the 67 votes required to end the filibuster, and the bill passed the Senate. President Lyndon Johnson signed it on July 2, 1964. Strom Thurmond, increasingly at odds with his own party, became a Republican just a few months later.

The struggle for equality is unfinished and is likely to remain so. But the fight itself is a necessary one without which Americans cannot say their nation truly stands for its noblest ideals. There is no better day than June 19 to remind us of the stakes in that fight—or what we stand to lose should we falter in it.

The “ struggle for equality” is not “ unfinished.” Racial discrimination is both illegal and socially unacceptable. Affirmative action programs have been in place for decades. Your virtue signaling might win you the approval of your colleagues but it is baseless.