John Wise (The Governor’s Son) Responds To John Brown’s Raid

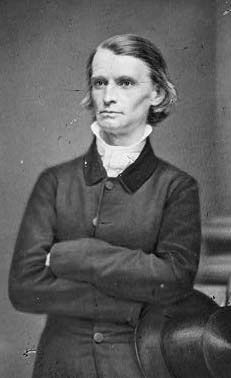

Twelve-year-old John Wise watched history happen. He would later recall “The End of An Era” in a book with the same title, detailing his memories of growing up in Antebellum Virginia, living through the Civil War, and actually embracing many of the changes that came through Reconstruction. As one of Governor Wise’s sons, young Johnny was often “in the know” about exciting events and mid-October 1859 was no exception.

Much of what he knew about the actual events in Harpers Ferry came from second sources, but his description of the day the new arrived in Richmond and a young boy’s response lend perspective and interest to the narrative of Virginia’s response to John Brown’s Raid:

In the afternoon of October 17, 1859, I was passing along Main Street in Richmond, when I observed a crowd of people gathering about the bulletin board of a newspaper. In those days, the news did not travel so rapidly as now; besides which, the telegraph lines at the place from which the news came were cut.

The first report read: —

“There is some trouble of some sort at Harper’s Ferry. A party of workmen have seized the Government Armory.”

Some another message flashed: “The men at Harper’s Ferry are not workmen. They are Kansas border ruffians, who have attacked and captured the place, fired upon and killed several unarmed citizens of the neighborhood. We cannot understand their plans or ascertain their numbers.”

By this time an immense throng had assembled, agape with wonder.

Naturally reflecting that the particulars of an outbreak like this would first reach the governor, I darted homeward. I found my father in the library, roused from his afternoon siesta, in the act of reading the telegrams which he had just received. They were simply to the effect that the arsenal and government property at Harper’s Ferry were in possession of a band of rioters, without describing their character. I promptly and breathlessly told what I had seen on the bulletin boards, and while I was hurriedly delivering my news, other messengers arrived with telegrams to the same effect as those posted in the streets. The governor was by this time fully aroused. He was prompt in action. His first move was to seize the Virginia code, take a reference, and indite a telegram addressed to Colonel John Thomas Gibson, of Charlestown, commandant of the militia regiment within whose territory the invasion had occurred, directing him to order out, for the defense of the State, the militia under his command, and immediately report what he had done.

Within ten minutes after the receipt of the telegram, these instructions were on the way. Similar instructions were flashed to Colonel Robert W. Baylor, of the Third Regiment of Militia Cavalry.

The military system of the State was utterly inefficient, having nothing but skeleton organization. The telegrams continued to come rapidly, describing a condition of excitement amounting to a panic in the neighborhood of Harper’s Ferry. The numbers of the attacking force were exaggerated, until some reports placed them as high as a thousand. The ramifications of the conspiracy were of course unknown.

I was promptly dispatched to summon the Secretary of the Commonwealth, the Adjutant-General, and the colonel and adjutant of the First Regiment. I found almost immediately all but the adjutant, for whom I searched long. At last this young gentleman was discovered, all unconscious of impeding trouble, playing dominoes in a German restaurant, and regaling himself with the then comparatively new drink of “lager.” Hurrying back with my last capture, we found the others assembled, and instantly the adjutant received instructions to order out the First Virginia Regiment at eight o’clock P.M., armed and equipped, and provided with three days’ rations, at the Washington depot.

In those days, the track ran down the centre of the street, and the depot was in the most popular portion of the city. News of the disturbance having gone abroad, it was an easy task to assemble the regiment; and, by the time appointed, all Richmond was on hand to learn the true meaning of the outbreak, and witness the departure of the troops. Company after company marched through the streets to the rendezvous. The governor transferred his headquarters to the depot, where he and his staff awaited the last telegrams which might arrive before his departure. Telegrams were sent to the President and to the governor of Maryland for authority to pass through the District of Columbia and Maryland with armed troops, that route being the quickest way to Harper’s Ferry. The dingy old depot, generally so dark and gloomy at this hour of the night, was brilliantly illuminated. The train of cars, which was to transfer the troops, stood in the middle of street. The regiment was formed as the companies arrived, and was resting in the badly lighted street, awaiting final orders.

The masses of the populace swarming about the soldiers presented every variety of excitement, interest, and curiosity.

As for me, my “mannishness” (there is no other word expressive of it) was such that, forgetting what an insignificant chit I was, I actually attempted to accompany the troops.

Transported by enthusiasm, I rushed home, donned a little blue jacket with brass buttons and a navy cap, selected a Virginia rifle nearly half as tall again as myself, rigged myself with a powder horn and bullets, and, availing myself of the darkness, crept into the line of K Company. The file-closers and officers knew me, and indulged me to the extent of not interfering with me, never doubting the matter would adjust itself. Other small boys, who got a sight of me standing there, were variously affected. Some were green with envy, while others ridiculed me with pleasant suggestions concerning what would happen when father caught me.

In time, the order to embark was received. I came to “attention” with the others, went through the orders, marched into the car, and took my seat. It really looked as if the plan was to succeed. Alas and alas for these hopes! One incautious utterance had thwarted all my plans. When I went home to caparison myself for war, the household had been too much occupied to observe my preparations. I succeeded in donning my improvised uniform, secured my arms, and had almost reached the outer door of the basement, when I encountered Lucy, one of the slave chambermaids.

“Hi! Mars’ John. Whar is you gwine?” exclaimed Lucy, surprised.

“To Harper’s Ferry,” was the proud reply, and off I sped.

“I declar’, I b’leeve that boy think hisself a man, sho’ nuff,” said Lucy, as she glided into the house. It was not long before she told Eliza, the housekeeper, who in turn, hurried to my invalid mother with the news. She summoned Jim, the butler, and sent him to father with the information.

Now Jim, the butler, was one of my natural enemies. However, the Southern man may have been master of the negro, there were compensatory processes whereby certain negros were masters of their masters’ children. Never was autocracy more absolute than that of a Virginia butler. Jim may have been father’s slave, but I was Jim’s minion, and felt it….

“What!” exclaimed the governor, on hearing Jim’s report of my escapade, “is that young rascal really trying to go. Hunt him up, Jim! Capture him! Take away his arms, and march him home in front of you!” Laughing heartily, he resumed his work, well-knowing that Jim understood his orders and would execute them.

….I was sitting in a car, enjoying the sense of being my country’s defender starting for the wars, when I recognized a well-known voice in the adjoining car, inquiring, “Gentlemen, is any ov you seed anythang ov de Gov’ner’s litter boy about here? I’m a-lookin’ fur him under orders to take him home.”

I shoved my long squirrel-rifle under the seats and followed it, amid the laughter of those about me. I heard the dread footsteps approach, and the inquiry repeated. No voice responded; but by the silence and the tittering, I knew I was betrayed. A great, shiny black face, with immense whites to the eyes, peeped almost into my own, and, with a broad grin, said, “Well, I declar’! Here you is at las’! Come out, Mars’ John.” But John did not come. Jim, after coaxing a little, seized a leg, and, as he drew me forth, clinging to my long rifle, he exclaimed, “Well, ‘fore de Lord! how much gun has dat boy got, anyhow?” and the soldiers went wild with laughter.

In full possession of the gun, and pushing me before him, Jim marched his prisoner home. Once or twice I made a show of resistance, but it was in vain. “Here, you boy! You better mind how you cut yo’ shines. You must er lost yo’ senses. Yo’ father told me to take you home. I gwine do it, too, you understand? Ef you don’t mind, I’ll take you straight to him, and you know and I know dat if I do, he’ll tear you up alive fur botherin’ him with yo’ foolishness, busy ez he is.” I realized that was even so, and, sadly crestfallen, was delivered into my mother’s chamber, where, after a lecture upon the folly of my course, I was kept until the Harper’s Ferry expedition was fairly on its way.

What I learned of events at Harper’s Ferry was derived from the testimony of others….

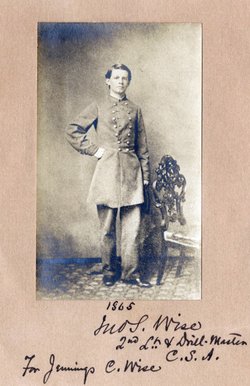

Note: John Wise was quite the little rebel at home and during the Civil War. He managed to sink the prize models of ironclads and threatened so many times to run off and join the Confederate army that his father packed him off to Virginia Military Institute, trying to keep him out of harm’s way. Instead, Wise fought with the Corps of Cadets at the Battle of New Market. He survived the war, studied law, and became a U.S. Congressman.

Splendid reading!