“But with blood” – John Brown, Violence, and Abolition in Kansas

On a cold December morning in 1859 in a jail cell in Charles Town, Virginia, John Brown reflected on his role in the desperate fight for abolition. Less than two months prior, he had led a small army of 21 men to raid the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry with the hope of inciting a major slave rebellion across the South. Even earlier, he had fought border ruffians and slaveholders along the Kansas-Missouri Border during the violent “Bleeding Kansas” era.

On a cold December morning in 1859 in a jail cell in Charles Town, Virginia, John Brown reflected on his role in the desperate fight for abolition. Less than two months prior, he had led a small army of 21 men to raid the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry with the hope of inciting a major slave rebellion across the South. Even earlier, he had fought border ruffians and slaveholders along the Kansas-Missouri Border during the violent “Bleeding Kansas” era.

Now, Brown was just hours from being executed by hanging for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. He quickly penned a testimony, which he handed to his jailer, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” Brown’s realization of the necessity – and moral justification – of violence in the fight against slavery was ultimately forged along the Kansas-Missouri border years before his Harpers Ferry Raid and consequent execution.

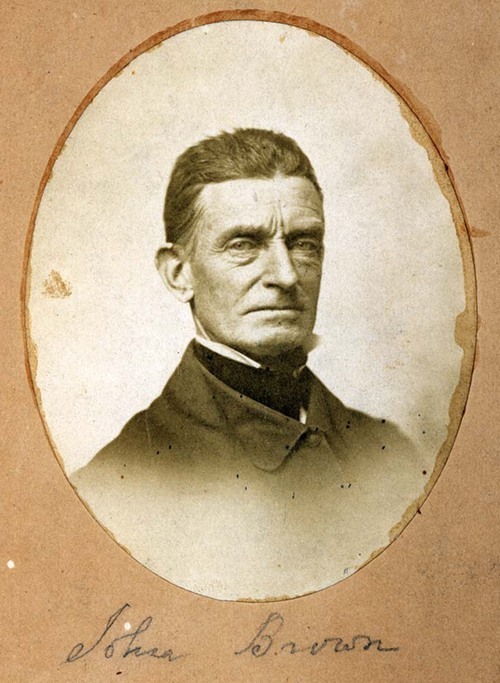

A lifelong abolitionist and devout Christian, John Brown arrived in Kansas in 1855, hoping to help bring the volatile territory into the Union as a free state. He was certainly in support of militancy, which was an unpopular opinion among the more-pacifist leanings of other abolitionists.

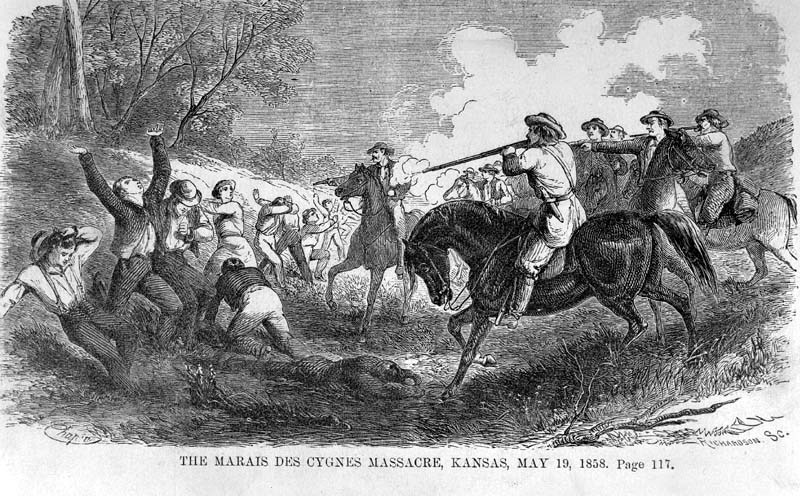

Many Northerners were convinced that pro-slavery factions would be victorious in securing Kansas as a slave-state, because Free-Staters “were not familiar with the use of the bowie-knife and revolver, and therefore not likely to place themselves in any dangerous proximity in the armed champions of Slavery.”[1] However, following the infamous caning of Senator Charles Sumner and the attack on Lawrence, Kansas in the Wakarusa War (both in May 1856), Brown finally snapped.

John Brown was convinced violence was the only solution, unlike pacifist anti-slavery advocates, whom he called, “cowards.” [2] Ultimately, as historian Nicole Etcheson writes in her book Bleeding Kansas, “his actions would profoundly alter the course of the free-state movement.”[3]

Just days after those pivotal events, the Cromwellian Brown sought revenge. From May 24-25, 1856, Brown and his band of armed abolitionists killed five pro-slavery men with broadswords at three different homes (Doyle, Wilkinson, and Harris properties) along the Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas. A brutal murder, Brown felt justified in his actions, saying “God is my judge. It was absolutely necessary as a measure of self-defence [sic], and for the defence of others.”[4] His war against slavery was far from over. In fact, it had just begun. Forever known as the Pottawatomie Massacre, these murders sparked a tremendous escalation of violence along the Missouri-Kansas border, a war that continued through the Civil War and beyond.

Brown’s war for abolition in Kansas continued through the remainder of 1856 at places, such as Black Jack, Palmyra, and Osawatomie. Though the violent conflict in Kansas spearheaded by Brown shaped and progressed the war for abolition, it did not come without loss for Brown. He lost his son Frederick at Osawatomie. Nonetheless, the fight continued for the abolitionist. By the end of the year, Brown and his sons left Kansas to fundraise for his abolitionist cause and begin planning a much larger raid – ultimately, at the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Brown’s devotion to the fight for abolition can be best summarized in a letter to his family in 1858: “Courage, courage, courage, the great work of my life; the unseen Hand that guided me and who has indeed holden my right hand.”[5]

While Brown was in jail in December 1859 about to be sent to the gallows, he certainly reflected on his cause for abolition. His time in Kansas transformed him into an abolitionist who was willing to take bold – even violent and deadly – actions for what he believed to be just. After Lawrence and the caning of Sumner, he firmly believed that the only way to fight slavery was with violence. Therefore, we cannot understand Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid without understanding his role in Kansas.

Sources:

[1] New Englander, November 1859, 1069.

[2] Brown, in Lawrence Daily Journal, December 3, 1879, in David Reynolds, John Brown: Abolitionist (New York: Vintage, 2005), 164.

[3][3] Nicole Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 109.

[4] Louis Rochames, ed., John Brown: The Making of a Revolutionary (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1969), 204.

[5] Letter from John Brown to Wife and Children, January 31, 1858, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, https://transcription.si.edu/view/14474/NMAAHC-2009_26_3_001.

John Brown was a cold-blooded murderer in Kansas who justified his crimes by quoting Hebrews 9:22 which states “…. without shedding of blood there is no forgiveness.” This passage refers to Christian redemption, and in no way justifies abolitionist crimes.

John Brown was a hero and a defender of human dignity against the incalculable evil that is Chattel Slavery. The “men” he rid this Earth of hardly warranted the name. Those who would see others in bondage for their own benefit deserve no mercy, and John Brown saw to it that those he caught received none.

As he said, “but with blood.”