The Civil War Versions of “NUTS”!

Welcome back, JoAnna M. McDonald

History does not quite repeat itself in the literal sense, but it does rhyme. For example, cheeky responses to surrender demands are apparently a tradition in American military history (and in military history in general). The most famous reply to an enemy surrender request occurred during the Battle of the Bulge. On December 22, 1944, the Germans demanded the submission of the American regiment in that sector. That unit happened to be part of the 101st Airborne Division, commanded by Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe. As many of you know, the reply McAuliffe sent back to the Germans was, “NUTS”![1]

Rewind 80 years and there are two responses that may not be as brief or as memorable but are just as audacious and interesting. Both incidents occurred in the Western Theater in October 1864. In each incident, a Confederate officer demands that a Union fort surrender. The commanders of the forts brazenly respond to their aggressors. One Union colonel even dares his opponent to, “come and take it,” a line that could date back as far as King Leonidas at Thermopylae.

So what, you might ask? The intent of the insolent language is defused by a polite tone in these negotiation letters. One Confederate officer goes as far as to state that he will not take prisoners if the fort has to be carried; then, he signs his demand “most respectfully.” True, all the senior officers involved graduated from West Point, and the military (and 19th century culture) taught that this was the way to properly close letters (military personnel to this day similarly close their emails). I am not suggesting that the officers should have used what I call aggressive combat language (cursing) but to me that would make more sense.

Are these Civil War surrender negotiations exactly like the one in the Battle of the Bulge? The intents are the same, but the details are different. McAuliffe’s remark does not mince words. It is brief and uncouth. With the Union and Confederate officers’ language, there is an incongruity. All of them, in varying degrees, juxtapose civility with the grisly subject of slaughtering one another. It seems insincere, and it is so ludicrous you might chuckle. It is macabre humor. There is, though, nothing humorous about threatening to take no prisoners, and it is a bit surprising to read in a Civil War context. Moreover, there are the moral or immoral and the professional or unprofessional issues of making such a threat, but we will leave this topic for another time. It is a bit heavy for the season. For now, read the following Civil War surrender negotiations and judge for yourself.

Around Allatoona, October 5, 1864

Commanding Officer, United States Forces, Allatoona:

I have placed the forces under my command in such positions that you are surrounded, and to avoid a needless effusion of blood I call on you to surrender your forces at once, and unconditionally.

Five minutes will be allowed you to decide. Should you accede to this you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoners of war.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully yours,

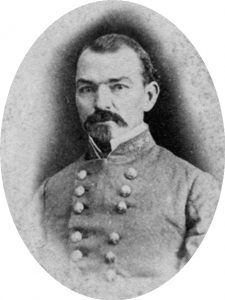

S. G. French,

Major-General commanding forces of Confederate States

***

REPLY

Headquarters Fourth Division, Fifteenth Corps,

Allatoona, Georgia, 8:30 A.M., October 5, 1864

Major-General S. G. French, Confederate States, etc.:

Your communication demanding surrender of my command I acknowledge receipt of, and respectfully reply that we are prepared for the “needless effusion of blood” whenever it is agreeable to you.

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

John M. Corse

Brigadier-General commanding forces United States.

***

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF TENNESSEE

IN THE FIELD, October 12, 1864.

To the Officer commanding the United States Forces at Resaca, Georgia.

Sir: I demand the immediate and unconditional surrender of the post and garrison under your command, and, should this be acceded to, all white officers and soldiers will be paroled [sic] in a few days. If the place is carried by assault, no prisoners will be taken. Most respectfully, your obedient servant,

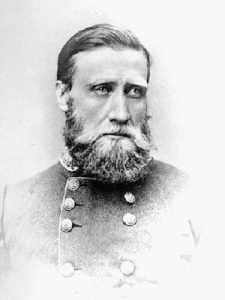

J. B. Hood, General

***

REPLY

HEADQUARTERS SECOND BRIGADE, THIRD DIVISION, FIFTEENTH CORPS,

RESACA, GEORGIA, October 12, 1864.

To General J. B. Hood:

Your communication of this date just received. In reply, I have to state that I am somewhat surprised at the concluding paragraph, to the effect that, if the place is carried by assault, no prisoners will be taken. In my opinion I can hold this post. If you want it, come and take it.

I am, general, very respectfully, your most obedient servant,

CLARK R. WEAVER, Commanding Officer[2]

JoAnna M. McDonald, Ph.D., has been a historian, writer, and public speaker for twenty years, specializing in strategic studies and strategic leadership. Currently, she is in an interim position as an environmental and historic preservation specialist.

Sources:

[1] The specific regiment in that sector was Company F, 327th Glider Infantry Regiment. For more on this story, see Kenneth J. McAuliffe, Jr. “The Story of the NUTS! Reply”, https://www.army.mil/article/92856/the_story_of_the_nuts_reply

[2] William T. Sherman’s Memoirs, vol. 2, 148–49 and 155.

That whole North Georgia Campaign (Oct-Nov 1864) is completely forgotten.