The Civil War and General Jim Mattis: Political-military relationship “trust up and down the chain” (Part 2)

In Call Sign Chaos, Jim Mattis stresses “trust up and down the chain must be the coin of the realm.” Official military doctrine supports this observation. A U.S. Army publication notes that command is “not a one-way, top-down process that imposes control on subordinates; it is multidirectional . . . feedback influences commanders” from above, below, and laterally. This is called a multidirectional command approach, and it is based on trust, respect, and communication—listening, learning, and aiding. Leaders (politicians and military) need to know when to follow; subordinates need to know when to lead. As he rose in rank from brigadier to full general, Mattis and the political administrations he dealt with, however, failed to apply a multidirectional command approach as the politicians had little to no trust, respect, or even communication with Mattis. So…I took a step back, turned the situation around, and asked is there a Civil War example that illustrates what occurs when a political-military relationship achieves trust, respect, and communication? The answer is yes.

During the final year, 1864–1865, President Abraham Lincoln, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, and Major General William T. Sherman used a multidirectional command approach. Before you go down the rabbit hole of “Sherman was an immoral !@#$ and a war criminal”, restrain yourself, gentle reader. Let’s shift gears and look objectively at the lessons we can learn. Lincoln, Grant and Sherman communicated with each other; and, although the President and Grant may not have fully agreed with Sherman, or were sure his plans would succeed, the superiors trusted and respected the subordinate general enough to let him try. This method allowed them to work as a team in their endeavor to orchestrate the comprehensive military plan that would restore the Union.

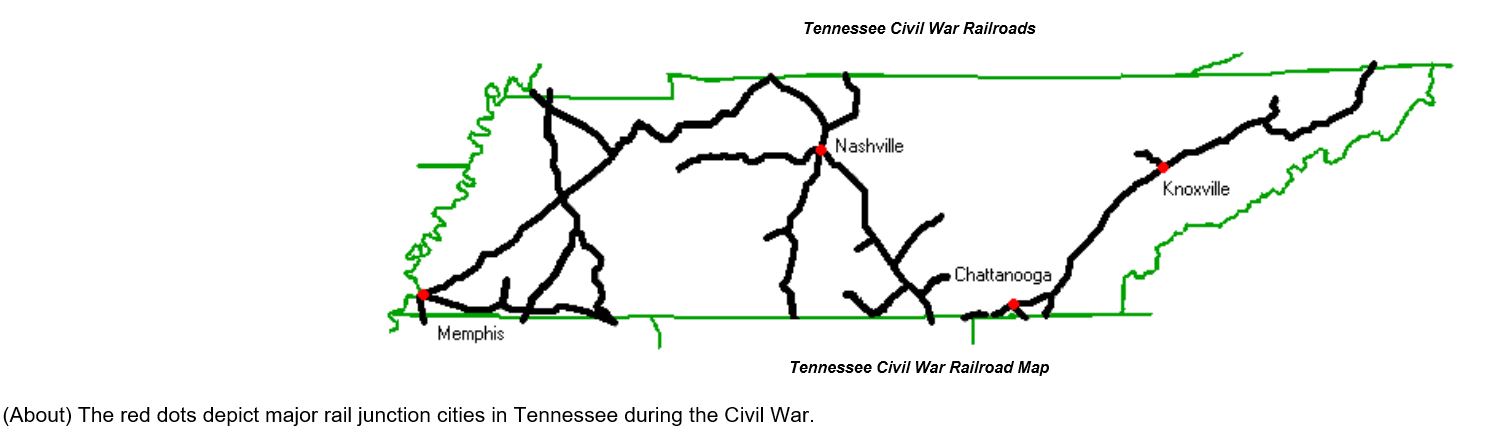

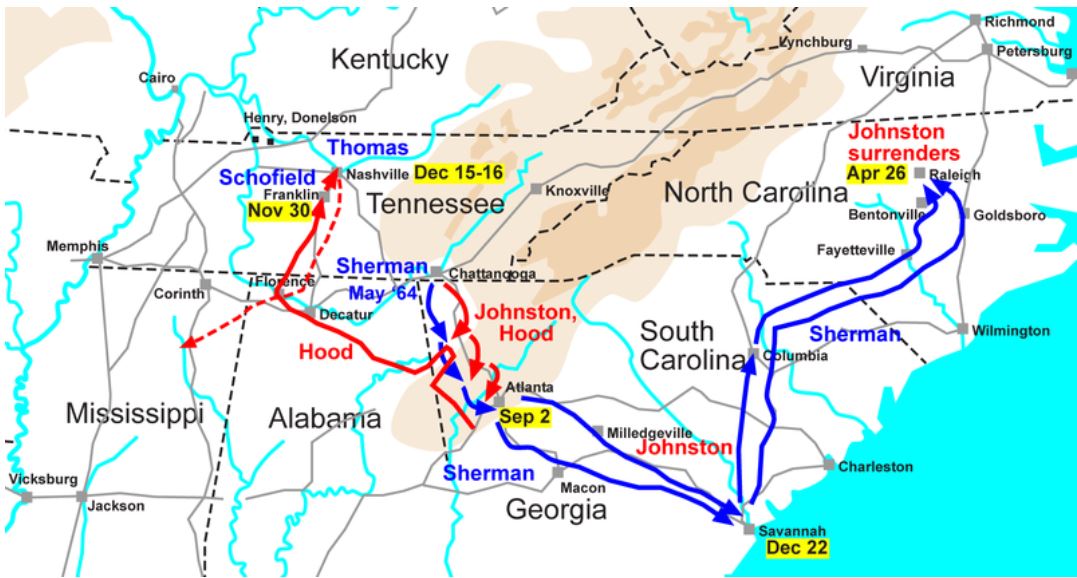

One of the first collaborative incidents occurred in the spring of 1864. In early April in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Sherman began to muster the men, ammunition, and stores for his impending operation into Georgia. There was a problem, though—there were not enough railroad cars to service both the military and civilians at the same time. To efficiently transport the massive amount of resources in a timely manner from Nashville to the staging area in Chattanooga, Sherman issued a general order limiting the use of the railroad to military use only. This prompted the citizens of East Tennessee, who supported the Union and relied on receiving their supplies from Nashville as well, to appeal to Lincoln. The President telegraphed his senior theater commander and asked if he could in some way accommodate the civilians’ request. Sherman candidly replied “it is demonstrated that the railroad cannot supply the army and the people. One or the other must quit, and the army don’t intend to, unless Joe Johnston makes us. . . I will not change my order, and I beg of you to be satisfied that the clamor is part humbug, and for effect; and to test it. . . .” Rather than take this negative reply personally and shoot back, “I am the Commander-in-Chief; do as I say,” Lincoln appreciated his subordinate’s blunt assessment, as well as the strategic-operational military challenges. Sherman’s role was vital to the success of the grand campaign. His preparation took precedence, and his army was granted full access to the railroads.

We see this multidirectional command approach once again in the late fall and early winter of 1864–65. It was in November, several months after the capture of Atlanta, Georgia, when Sherman reassessed the war’s political-military momentum. He suggested to Grant (and indirectly to Lincoln) that if he was allowed to adapt his portion of the military plan he could shorten the conflict. The original directive called for Sherman to first move against the Confederate Army of Tennessee and “break it up.” Once he had accomplished this, he was “to get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as he could and inflict all the damage he could against their war resources.” Sherman contended he could accomplish both goals simultaneously by splitting his force. He would send Major General George Thomas, with a sufficient force, to deal with the Confederate Army of Tennessee. At the same time, he (Sherman) would drive a large contingent through Georgia and up into the Carolinas with the intent of making “its inhabitants feel that war and individual ruin [were] synonymous terms.”

At this point, the telegraph began to clatter as the General-in-Chief and his theater commander had what is called a command-feedback discussion. Initially, Grant had misgivings. He felt Sherman should stay with the original plan. The main reservation was that Thomas had a reputation of moving slowly. What if he failed to destroy the Army of Tennessee, and what if the Confederates began cutting major lines of communication in the Western Theater; could Sherman get enough troops back to contend with them? Sherman guaranteed “Pap” Thomas would have enough men to ensure success in his assignment. If by some unforeseen chance the Confederates threatened Middle Tennessee, “Uncle Billy” would move in that direction. That was what Grant needed to hear. Trusting in his subordinate’s confidence, the General-in-Chief deferred to his theater commander’s professional judgement: “I say, then, go on as you propose.” With these few words, Sherman’s initiative was unleashed. A month later, he presented Savannah as a Christmas present to Lincoln. In his congratulatory reply to the general, the President stated he had been anxious “if not fearful” but “feeling you were the better judge . . . I did not interfere. Now, the undertaking being a success, the honor is all yours; for I believe none of us went further than to acquiesce.”

In late March and early April 1865, another critical discussion transpired between the Commander-in-Chief and his senior army and naval officers. The first subject of concern was how to end the war. Grant and Sherman surmised one more large-scale battle would probably have to be fought. This notion was quite unpopular with the Chief Executive. More than once during the conversation, Lincoln “exclaimed that there had been blood enough shed, and asked [his commanders] if another battle could not be avoided.” Sherman explained that the Northern officers would try to comply but none of them could entirely control that event; that determination lay with the enemy, and General R. E. Lee would most likely be forced to fight one more desperate, bloody battle. Again, this was not the explanation the President wanted, but it was an honest assessment of the military situation, and the one he needed to hear. He accepted the fact that the enemy always gets a vote.

During the senior level talks, conversation then turned to what should happen to the Southern men after the Confederate armies surrendered. Lincoln made his intent clear. He desired all Southern soldiers be sent back to their homes, to work on their farms or in their shops. All the military officers agreed, and the directive went out to the theater commanders. In compliance with President Lincoln’s wishes, every U.S. military officer who oversaw the surrender of a Confederate army, allowed each Southern officer and enlisted man to return to their homes.

The command approach adopted by Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman was a political-military partnership. When a difference of opinion arose, respect led them to engage in professional, unemotional, but critical dialogue. Respect, combined with trust, allowed the leaders to listen and follow a subordinate’s initiative, as well as provide a command climate in which subordinates felt comfortable offering realistic assessments of the military situation to their Commander-in-Chief. Finally, humility and a clear, strategic-political compass kept the discussions and decisions focused on the most effective and efficient military course of action to restore the Union.

The command approach adopted by Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman was a political-military partnership. When a difference of opinion arose, respect led them to engage in professional, unemotional, but critical dialogue. Respect, combined with trust, allowed the leaders to listen and follow a subordinate’s initiative, as well as provide a command climate in which subordinates felt comfortable offering realistic assessments of the military situation to their Commander-in-Chief. Finally, humility and a clear, strategic-political compass kept the discussions and decisions focused on the most effective and efficient military course of action to restore the Union.

Wait, what about the Confederates . . . is there an example illustrating this multidirectional command approach between say a commanding general and his subordinate senior officers? We will soon see.

Further Reading:

Fellman, Michael. Citizen Sherman: A Life of William Tecumseh Sherman. New York: Random House, 1995.

Grant, U.S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 Vols. New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885–1886.

Mattis, James and Bing West. Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead. New York: Random House, 2019.

Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces. Washington, D.C.: Department of Army, July 2018.

Sherman, William T. Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. 2 Vols. 2nd ed. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1875.

Trudeau, Noah Andre. Lincoln’s Greatest Journey: Sixteen Days that Changed a Presidency, March 24 – April 8, 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA. Savas Beatie, 2016.

A very interesting and thought-provoking post. Thanks for sharing.

–Chris Barry

Perhaps we will return to the importance of the study of history! It’s wisdom teaches what to repeat and what NOT to repeat.