Ending The War: General Hancock & The Surrender? (Part 1)

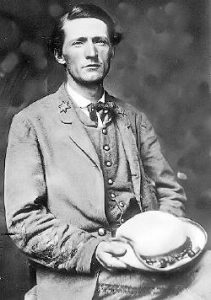

He had won his general stars on the battlefield, held the lines at Gettysburg, and been a trusted corps commander during the Overland Campaign. He had survived painful injury and returned to field command. He was a Democrat in politics and a career military officer who had put his duty to the Union first. Successful and legendary, Winfield Scott Hancock had two important, though sometimes overlooked moments, during the ending of the Civil War. Could he convince the Gray Ghost (John Mosby) to surrender? Would he carry out his assigned military duty and hang a woman accused of conspiring in a presidential assassination? The Civil War was ending in the spring of 1865 and Hancock was far from the active battlefields, but he still held crucial roles in the concluding scenes of the conflict.

General Winfield S. Hancock is best remembered for battlefield leadership, especially as commander of the II Corps of the Army of the Potomac during Gettysburg and the Overland Campaign. However, he did not end the war with a field command. Due to continuing complications from his Gettysburg wound, Hancock left active field service in November 1864 but stayed in military service. First, he tried to recruit for the Veteran Corps, using his reputation and influence. By February 1865, he was ordered to take command of the Middle Department and establish his headquarters at Winchester in the lower Shenandoah Valley. As General Sheridan pulled out of the Valley, chasing Early’s Confederates and heading for Petersburg, Hancock took over the Federal occupation of the Valley.

Hancock’s experiences in Winchester were relatively quiet and uneventful compared to his Union predecessors who usually faced the hostility of civilians along with Confederate military and partisans. Only John Mosby’s Rangers operated in the area, and when news of Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia reached the Valley, Hancock faced the duty of communicating with the Rangers and getting them to surrender. He started with a published address to the citizens of Winchester and the surrounding region, knowing that it would quickly reach Colonel Mosby:

The Major General Commanding trusts that the people to whom this is sent will regard the surrender of General Lee with his army as Lee himself regards it, as the first great step to peace, and will adapt their conduct to the new condition of affairs and make it practicable for him to exhibit towards them every leniency the situation will admit of. Every military restraint shall be removed that is not absolutely essential, and your sons, your husbands, and your brothers shall remain with you unmolested.

After this reconciliatory beginning, Hancock went on to declare that he would not permit partisan bands in his department and that he purposed to “destroy utterly the haunts” used by these groups. He also threatened that if the partisan bands continued operating “every outrage committed by them will be followed by the severest infliction.”

Additionally, Hancock sent copies of letters from Lee and Grant as proof of the surrender at Appomattox directly to Mosby. The situation was compounded by orders from General Halleck that John Mosby would be the exception to the generalized parole. The situation and negotiations would be more complicated than Hancock had anticipated.

On April 16, 1865, as the general in Winchester grappled with the news of Lincoln’s assassination and kept troops alert for the murderer on the run, a letter arrived from Colonel Mosby. Dated April 15, the document read:

General: I am in receipt of a letter from your chief of staff, Brigadier General Morgan, including copies of correspondence between Generals Grant and Lee, and informing me that you would appoint an officer of equal rank with myself to arrange details for the surrender of the forces under my command. As yet I have no notice through any other source of the facts concerning the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, nor, in my opinion, has the emergency yet arisen which would justify the surrender of my command. With no disposition, however, to cause the useless effusion of blood or to inflict on a war-worn populace any unnecessary distress, I am ready to agree to a suspension of hostilities for a short time in order to enable me to communicate with my own authorities or until I can obtain sufficient intelligence to determine my future action. Should you accede to this proposition, I am ready to meet any person you may designate to arrange terms of an armistice.

Hancock agreed to the ceasefire and made it effective immediately. Next, he set up a meeting for Mosby on April 18. Official correspondence from General Grant’s headquarters authorized Hancock to negotiate and accept the Mosby Rangers’ surrender. Secretary of War Staunton telegraphed with some additional insight, cautioning Hancock to be wary of a surprise attack during the meeting and adding, “If Mosby is sincere he might do much toward detecting and apprehending the murderers of the President.”

On April 18 at Carter Hall near Millwood, Virginia, Brigadier General George H. Chapman carried Hancock’s directives and met with Colonel Mosby. The meeting proceeded amiably and included a meal. The Federals offered the Rangers the same terms given to Lee: surrender their weapons, sign the paroles, and depart for their homes. Mosby had already told his men that they were free to leave, take parole, and go home, but he pressed for a further delay for an official surrender, claiming that he had no orders or news from Richmond and wanted to see what would happen between Johnston and Sherman in North Carolina. The meeting accomplished little, except the extension of the armistice for two more days.

By April 20, Mosby’s messengers had returned with confirmation of Lee’s surrender and direct advise from Lee to disband the Rangers. That day’s meeting took place at Clarke’s tavern near Millwood, but the mood had changed. Chapman refused to extend the terms of the truce or negotiate new terms which irritated Mosby. When an uninvited Ranger made the claim that Yankee cavalry surrounded the area and the Confederates would have to fight for their lives, Mosby avoided bloodshed but walked out of the meeting. The following day at Rectortown Mosby disbanded his Rangers.

Hancock did not get the formal surrender his superiors were looking for, and he did not capture and hold Mosby. However, on April 22 about 200 Rangers appeared in Winchester and formally signed parole papers. Hancock himself went and talked with the paroled men. By June 1865, nearly 800 of Mosby’s Rangers had signed parole papers.

The period between April 10-22 set a pattern for General Hancock in the Reconstruction Era. He would accomplish the objective, but not always the way his commanding officers expected and usually with a spirit of leniency and reconciliation. However, perhaps Hancock’s willingness to allow the truce and meetings fostered a more peaceful ending and the disbandment of the Rangers. Other generals with harsher views potentially could have prolonged the war in the region.

Perhaps Dr. Monteiro, a member of Mosby’s Rangers, summed it when he described the moment when Hancock met him with “kind expressions of sympathy and regard, when I expected a harsh, cruel or haughty reception.” Though not present with Grant and the Army of Potomac in the field, Hancock extended the lieutenant general’s sentiments and feelings at Appomattox to the correspondence and negotiations which led to the peaceful disbandment—though not surrender—of Mosby’s Rangers.

To be continued with a look at Hancock’s role in the execution of assassination conspirators…

Sources:

Hancock, Almira. Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock. New York, 1887.

Jordan, David M. Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life. Indiana University Press, 1996.

Tucker, Glenn. Hancock The Superb. Morningside Bookshop, Ohio, 1980.

Wert, Jeffrey D. Mosby’s Rangers. Simon and Schuster, New York, 1990.

Hi,

Can you were right about Hancock and his response to the riots in Mobile Alabama in 1867?

https://history.army.mil/html/books/075/75-18/cmhPub_75-18.pdf

Bryce