A very private war: Rocky Face Ridge, May 8 to 11, 1864

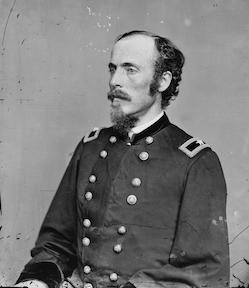

On the morning of May 8. 1864, Colonel Emerson Opdycke’s 125th Ohio infantry drew an unenviable assignment. One of the regiments comprising the Third Brigade, Second Division, of O. O. Howard’s Fourth Corps in the Army of the Cumberland, the 125th was a veteran command, and ably led. Colonel Charles G. Harker was their brigade commander, a regular who had proven himself in combat; and Opdycke had led the 125th since it entered Federal service, and led them into their baptism of fire at Chickamauga the previous September.

Now they were advancing against the Confederate Army of Tennessee, heavily entrenched at Dalton, Georgia, and secure behind the looming wall of Rocky Face Ridge. Assaulting Rocky Face seemed a nightmarish proposition. It was a knife-edge of a mountain, heavily palisaded on its western face. It loomed hundreds of feet over the valley below. The few gaps that pierced it were easily defended, and, at Mill Creek, dammed and flooded so as to make the approach almost impossible.

Harker’s brigade, however, was situated at the mountain’s northern end, where it descended to a series of low, easily scaled ridges. Even better, the Confederate lines did not reach that far north, having turned east to cross Crow Valley, defending Dalton’s northern approaches. These circumstances led to Harker’s orders: “To scale the side of the mountain and try and effect a lodgment on the ridge, supposed to be in possession of the enemy.” For this task, Harker turned to Opdycke and his Ohioans. “He would support me,” Opdycke wrote, “with the rest of the brigade.”

After a reconnaissance, Opdycke selected a spot where he thought he could ascend. A handful of Confederate skirmishers were present, observing, so Opdycke elected to try and fool them: “I moved to the northern point of the ridge and made a demonstration . . . as if I intended to pass round to the eastern side and go up there: then suddenly withdrew.” While the rest of the brigade continued to this display, Opdycke “commenced ascending obliquely the western side.”

The stratagem worked. They gained the crest with but minor opposition. Private Jesse B. Luce of Company B recorded the day’s events in his diary: “Sabith morning. Lift [Left] the camp at six am. Marched in line of battle around Rocky Face. It was the wrong way but found the Rebel pickets and then fell back half a mile. Companies “A” and “G” were deployed as skirmishers. Our company was the center reserve. We took the north end of Rocky Face without losing a man, and then advanced to the South end. Skirmishing commenced pretty brisk—two of the boys in our regiment was wounded. Col. Opdycke ordered our Co. forward and fired—went forward eight or ten rods and fired, forced down. Six of our boys were wounded, and one killed.”

Remarkably, this fight took place along a ridge Opdycke described as “so narrow and rocky” that it was “impossible for more than four men to march abreast.” The Confederates, Alabamians from Edmund Pettus’s brigade, constructed a series of short, arrow-shaped stone walls, one behind the other, as defenses. Each flank dropped off precipitously, making end-runs extremely difficult. Fortunately for the Federals, their surprise appearance and the thinness of the Confederate line here made for limited opposition.

The 20th Alabama infantry held the summit, having been shifted to the top of the mountain from their recently completed earthworks only on May 6th, along with the rest of Pettus’s command, to defend what Confederate divisional commander Major General Carter Stevenson called “the key to my position.” Originally Pettus had only anchored the crest with “a regiment of rifles,” but the developing threat caused Stevenson to shift the rest of the brigade there as well.

The fight atop the ridge became almost a private war. Both sides were effectively isolated by the height and steep slopes, while the narrowness of the crest limited the number of fighters on each side to a handful at any one time. Opdycke’s Ohioans bore the brunt of that action on the Federal side, but the paucity of detail from the Alabamians leaves us the sketchiest of images of their fight here.

However, this private affair lasted for several days. The day after the 125th’s initial assault, on May 9 in a letter to his wife Lucy, penned (really penciled) “in the middle of a sharp skirmish,” Opdycke detailed the fight so far: “My losses [yesterday] were four killed and eighteen wounded, two of them mortally. . . . This is a very important point gained, as from it we can see Dalton and overlook the rebel works, troops, and maneuvers. . . . The ridge is a mile or so longer, and we are slowly driving the enemy off.” Best of all thought Opdycke, “[We] got two pieces of artillery up last night, by hard work all night. . . . I am now writing while the regiment is waiting the advance of the skirmish line, the balls whiz about us saucily, cutting off limbs, one of which just fell on this paper. A ball a few moments ago struck above my head, and dropped down upon my hat rim.”

Despite Opdycke’s optimism, the Rebels were not in fact about to give up any more of the mountain. General Stevenson reported that “on the 9th instant the enemy, formed in column of divisions, made a heavy assault upon the angle in Pettus’s line. The fight was obstinate and bloody, but resulted in a complete success to us.”

Of course, the fighting at Dalton was soon overshadowed by the much more famous Union maneuver via Snake Creek Gap, where the Union Army of the Tennessee almost severed Joe Johnston’s supply line and turned his Dalton position into a giant trap. That threat forced the Confederates to abandon Dalton and triggered the much larger battle of Resaca, fought May 14-15, 1864.

Today, while much of Rocky Face Ridge is in public hands—owned in part by the State of Georgia, part-owned by Whitfield county, and part by the American Battlefield Trust—it is not easily accessible. This is especially true for that part north of Mill Creek Gap, where Opdycke’s Ohioans clashed with the Alabamians. There is only a utility road to the top and securing permission to go up can be difficult.

That said if you do have the chance to visit, by all means, do so.

Excellent. Thanks for posting this and the terrain photos.

From his splendid books and one of his battlefield tours of Chickamauga, I can say that there are few that know terrain as well as Dave Powell.

No question. The three Chickamauga books and the Maps book are first rate. I’ll add Failure in the Saddle. And the upcoming Tullahoma book co-authored with Eric W is on the order list.

Does any one of you who are commenting have knowledge or information about the participation of Confederate Gen. Evander McIver Law at Chickamauga?

Your best bet is to consult Dave’s books. Law assumed command of Hood’s Division during the battle and took part in Longstreet’s massive assault on Day 2(3). By that point issues of promotion/non-promotion had already poisoned the well between Law and Longstreet and it only got worse as Longstreet’s corps stayed in Tennessee.

Now there is Rocky Face Ridge Park, with great trails from Crow Valley Road to the top.