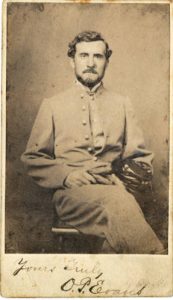

Oliver P. Evans: A Colorbearer at New Market

May 15 marked a defining day and the ending day of Oliver Perry Evans’s life, but not in the same year.

However, his story began on June 2, 1842, when he was born near Jackson Court House, Virginia (now West Virginia). Nineteen years later, on January 15, 1862, he matriculated at Virginia Military Institute. Older than the average seventeen-year-old cadet, Evans studied and drilled at VMI and seemed to make friends easily. By 1864, he had promoted to second cadet sergeant in Company B of the Corps of Cadets.

Like his fellow cadets, Evans likely wanted to get to a battlefield. It’s a little mysterious why at age twenty-one he remained a cadet, but for many of the young men at VMI, family pressure kept them at the barracks and classrooms. Many families had already lost boys in the Civil War and were desperate to keep a son or two away from the fighting in a respectable way. However, most of the cadets saw this desire for safety as total “imprisonment” and way to simply miss out on all the excitement and glory of war.

The so-call prison sentence ended on May 10, 1864, when a message arrived from Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, ordering the Corps of Cadets to join his gathering army at Staunton to act as reserves in the coming battle against Union General Franz Sigel. Thrilled, the cadets cheered when they heard the news that night and readied for their long march, down (northward) to Staunton. After a long march of forty miles, the corps arrived at their destination two days later.

On May 13, Breckinridge and the Confederate army headed north. A forced march in the night of May 14-15 placed the army just south of the town of New Market, Virginia—able to occupy the high ground which Confederate cavalry had held for the approaching infantry.

The Corps of Cadets breakfasted, endured taunts from veteran soldiers, and formed for battle. Since the usual colorbearer for the corps was away on a furlough, Cadet Evans was selected to carry the emblazoned white banner. Standing six feet, two inches tall, he made a conspicuous target. Colorbearers routinely got shot since they made easier targets and forcing an enemy flag down could have an effect on military order and morale. Miraculously, Evans survived the day without recorded injury and took a visible role, long remembered by his comrades and later immortalized in art.

When Breckinridge decided to advance his army down Shirley’s Hill and drive the Federals off Manor’s Hill, he ordered the reserve force, including the Corps of Cadets, to follow at a distance. Still, the cadets came under artillery fire and the impact of one shell blasted many off their feet. They rallied, formed on Evans and the flag and continued their march down the incline. Some civilians who observed the cadets advance noted the flag and believed it’s white coloring and the troops’ steady discipline could mean only one thing: the French had come to reinforce the Confederacy!

“Brave Evans, standing six feet two, shook out the colors that for days had hung limp and bedraggled about the staff, and every cadet leaped forward, dressing to the ensign and thrilling with the consciousness that this was war…”

New battle lines formed about a mile north in the fields and along the fences of Jacob Bushong’s farm. As the fighting intensified again, a gap opened in Breckinridge’s lines, and he did not have enough troops in the field to close up the opening. He made the decision to send in the Corps of Cadets to stabilize the line.

Rushing forward, the cadets moved through open ground where artillery felled several of their comrades. The companies split around the house and outbuildings of the Bushong Farm, came together again in the orchard, and rushed to the split rail fence, coming into the battle line between Woodson’s Missourians and the 26th Virginia Battalion.

“The men were falling right and left. The veterans on the right of the cadets seemed to waver. Colonel Shipp went down. For the first time the cadets appeared irresolute. Some one cried out, ‘Lie down!” and all obeyed, firing from the knee, – all but Evans, the ensign, who was standing bolt upright, shouting and waving the flag.”

“Manifestly, they, the cadets, must charge or fall back. And charge it was; for at that moment, Henry Wise…sprang to his feet, shouted out the command to rise up and charge, and moving in advance of the line, led the Cadet Corps forward to the guns. The battery was being served superbly. The musketry fairly rolled, but the cadets never faltered. They reached the firm greensward…where the guns were planted… Before the order to limber up could be obeyed by the artillerymen, the cadets disabled the teams, and were close upon the guns. The gunners dropped their sponges, and sought safety in flight. Lieutenant Hanna hammed a gunner over the head with his cadet sword. Winder Garrett outran another and lunged his bayonet in him. The boys leaped on the gun… Evans, the colorbearer sergeant, stood wildly waving the cadet colors from the top of a caisson.”

From first coming under fire at Shirley’s Hill to climbing on the captured cannon, Cadet Oliver P. Evans had a visible and unforgettable part in the history and legend of the Virginia Military Institute Corps of Cadets at the Battle of New Market. But where the paintings leave their depiction of him is not where the story ends.

In the aftermath of the battle, Evans visited Thomas G. Jefferson, a badly wounded cadet who was cared for at the Clinedinst home in New Market. Evans kept watch with Moses Ezekiel—Jefferson’s roommate—through the night and was present when the young cadet died.

The Battle of New Market and the rest of the Civil War had a profound impact on the cadets, but the majority survived the conflict and faced the challenge of finding their way in the post-war south. Evans returned to Lexington, Virginia, and studied law at Washington College, adjacent to VMI’s burned ruins.

Looking for new opportunities, Even traveled to California and settled in San Francisco, opening a law practice. One of his clients – Judge S. C. Hastings – had him prepare the act for the legislature which founded the Hastings School of Law – Evans served as one of the school’s first directors and a professor. Later, the California governor appointed Evans to serve on the Fourth District Court for San Francisco. By 1880, he became one of the state’s first Superior Court Judges elected for San Franscico and served for three years.

Married in 1876, he and his wife, Nora M. Ryan Evans, had four children. One of their sons graduated from University of California and Hastings College of Law and later followed his father’s example for a successful career.

Evans suffered paralysis, possibly caused by a stroke, in 1903. He lived another eight years but grew weaker. Oliver P. Evans—VMI Cadet, colorbearer in the Battle of the New Market, and California judge—died quietly at his home in Berkeley on May 15, 1911.

It was forty-seven years to the day since the Battle of New Market.

Sources:

Couper, William. The Corps Forward: Biographical Sketches of the VMI Cadets who fought in the Battle of New Market. (VMI, 2005)

VMI Digital Archive: Moses Ezekiel to Joseph R. Anderson, 1904: https://archivesspace.vmi.edu/repositories/3/digital_objects/170

Wise, John. End of an Era: The Story of a New Market Cadet. 1889.

Thanks for this interesting article.

Very interesting. Thanks.

I just received “Call Out the Cadets”, and look forward to reading it.

Great story very interesting.

Great article about Cadet Evans! I am wondering if VMI cadets were subject to the Confederate draft or were exempt. I know a number of them wanted to fight for the Confederacy. What was the relationship between VMI and the Confederacy?

Many, if not most, of the Confederate soldiers in this battle were from West Virginia. There were some Union soldiers from West Virginia in Sigel’s troops, but the 1st WV was mostly from Ohio and Penn. James Burns, who won the medal of honor in this fight, was from Ohio.

Beautifully written article, Sarah. Simple and elegant. So he was at my Alma mater when Lee was its president.

He was the best friend of my great grandfather Charles Sayre, who ran away from home in Jackson County, W.Va. in 1864 and joined the 22nd Va. Regiment, which, it appears from a list on the internet, Evans had joined earlier before he ended up at VMI. Charles was at the Battle of New Market and watched as the cadets charged the hill to see if the flag fell. He knew Evans was carrying the flag. Both lived and survived the war. Sayre returned to W.Va. in early 1865 with the promise of a promotion to officer if he got a horse and returned (at least this is what came down through his daughter, my great aunt). He got the horse but was captured leaving by the federal “home guard” and imprisoned. He was visited in jail by a widow and her young daughter. Years later he married the daughter, whose father had been murdered by the “home guard” early in the war. When Evans left for the west he supposedly gave my great grandfather a baby crib, which has descended to me.