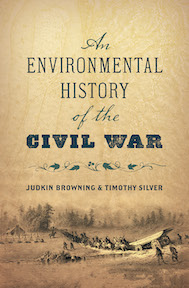

BookChat with Judkin Browning and Timothy Silver, authors of An Environmental History of the Civil War

I was pleased to spend some time recently with a new book by historians Judkin Browning and Timothy Silver. Drs. Browning and Silver are professors at Appalachian State University, where Browning is professor of military history and Silver is professor of environmental history. Together, they are the authors of An Environmental History of the Civil War, a new release from the University of North Carolina Press (click here for more info).

I was pleased to spend some time recently with a new book by historians Judkin Browning and Timothy Silver. Drs. Browning and Silver are professors at Appalachian State University, where Browning is professor of military history and Silver is professor of environmental history. Together, they are the authors of An Environmental History of the Civil War, a new release from the University of North Carolina Press (click here for more info).

Drs. Browning and Silver were kind enough to take a few minutes to chat with me about their book.

1) We think of the war as a military event with huge social, political, and economic ramifications. Why is it also important to think of the Civil War as an environmental event?

The war was not just a military conflict, but also a biotic or an ecological event. The war fundamentally altered relationships between Americans and nature, leaving an environmental legacy that we still live with today. Adopting an ecological approach offers a holistic view of the war. Military strategy and battles were important, but so were a host of other factors (which shaped those military events), including disease, weather, the need for sustenance, animals, the biological reality of death, and the vagaries of terrain and natural vegetation.

2) Because of my own background, when I think of the war and environmental history, I think of the Romantic literary movement—Cooper, Emerson, Thoreau, those folks—and art by painters of the Hudson River school. And then the war came along. What happened when that artistic/literary thinking about nature ran up against the realities of war?

That’s a great question. As most historians know, Transcendentalist ideas about finding God in nature had been percolating in American culture for several decades before the war. In the East, four years of constant fighting left the natural world in shambles, thus destroying what many regarded as God’s handiwork. Aaron Sachs is one historian who has shown how artists and intellectuals who had formerly praised nature began to note “the grim parallel” between forests and men mangled in battle. Both trees and soldiers had lost limbs or had once-healthy body parts reduced to stumps as a result of the conflict.

It’s probably more than coincidence, then, that on May 17, 1864, shortly after the Battle of the Wilderness, that Senator John Conness of California introduced legislation to protect Yosemite Valley and a stand of giant sequoias. That same year, George Perkins Marsh published Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. Many scholars regard Marsh’s work as the first environmental history and the first work to chronicle humanity’s adverse effects on American nature. With the eastern landscape torn asunder, the West with its apparently unspoiled majestic scenery, became the place to contemplate God and seek healing from the mental and physical anguish brought on by four years of war.

Though much work still needs to be done, some historians argue that the Civil War played a significant role in the origins of the American conservation movement. In 1872, Ulysses S. Grant, who knew better than most the effects of war on land and people, signed the bill that created Yellowstone National Park. One of the more important legacies of the Civil War might be that it not only changed the American landscape, but also altered the ways in which Americans thought about and began to take care of the natural world.

3) People seem relatively familiar with such factors as weather, geography, and topography, but what other environmental factors tended to impact operations and battles and armies?

Because the war put people in motion, it created a near ideal environment for the propagation and spread of certain diseases. Because many soldiers came from isolated rural areas, measles, mumps, and various respiratory infections often ran rampant in the training camps as soldiers gathered for the initial musters. Confederate General John B. Gordon noted that new recruits “ran through the whole category of complaints that boyhood and babyhood are subjected to.” Quarantine might help, but usually commanders just had to wait until the epidemics ran their courses.

Animals were critical to the war effort. Every wagon or piece of artillery used in the conflict moved by horse or mule power. Hogs and cattle provided the protein that kept soldiers on the battlefield. Once brought together from diverse regions of the country, animals also became subject to diseases and parasitic infections. Disposal of dead animals in the wake of major battles also posed major environmental problems. It took years for the South to recover from the loss of so many horses and mules. The war also provided a boost to veterinary medicine as the nation became more aware of animal health.

Other historians have written extensively about the religious and cultural effects of so many human deaths in the war. But death was also a distinctly ecological event, one that brought soldiers and their relatives face to face with the ways in which nature reclaimed human bodies. Like dead animals, dead people had to be disposed of, sometimes quickly. Human bodies also became environmental commodities–taken from the battlefield, embalmed or otherwise preserved from decomposition (momentarily at least) and shipped to distant locales for proper burial. Dealing with the dead became a thriving business during the war.

4) As someone who lives in Fredericksburg, I was delighted to see that you started with Ambrose Burnside’s Mud March. Why did you decide to use that as your starting point?

We chose to start there because it is perhaps the most famous “environmentally-influenced” campaign of the war. While terrain and weather are important at every battle, and military historians pay attention to them, the failed “Mud March” is the classic example of a campaign in which the armies could not conquer the natural world. It’s the only campaign of the war denoted by a weather-induced feature (mud) rather than a geographic one. We thought that by starting with a campaign that is commonly understood to be one in which the environment played a big role, we could show the reader how an environmental history consists actually of more than just examining the weather and terrain.

5) Since you frame the war as “a significant episode in the changing story of the American environment,” you made an effort to focus on story as you wrote the book. Why is story so important in this case?

For all our concern with nature and its chaotic nonlinear ways, we could never escape the fundamental notion that wars are human endeavors with clear beginning and ending points. So in the end, we decided to tell the story of war and the environment within a chronological framework, focusing on certain environmental themes during specific seasons of war. Thus, sickness during the initial musters and battles from spring to winter of 1861, the crucial role of weather between winter 1861 and fall 1862, and so on.

It’s not a perfect organizational scheme and we occasionally look forward or backward a bit in each chapter to provide context or complete a story. And, without delving too deeply into narrative theory, we just believe that storytelling is an effective way to reach a wide general readership, which was one of our goals for the book.

6) As a result of that approach, you talk in your intro about “the difficult choice” to focus on certain themes at certain times of year because that approach better lent itself to linear storytelling. Why was that choice difficult, and what were some of your other options?

Our initial ideas called only for thematic chapters: Sickness, Food, Terrain, etc. each of which would cover the entire war. Tim, especially, thought such an organizational scheme more closely reflected the ways of the natural world and would provide a new perspective on the war. So the choice to follow the war’s well known chronology was difficult. Mark Simpson-Vos, our editor at UNC Press, helped convince us that using chronology and offering a thumbnail sketch of the war would actually sharpen the environmental analysis. Turns out he was right.

7) You say that the war left “a legacy that affected relationships between Americans and nature for decades to come.” How would you characterize that legacy?

On the positive side, the war led to improvements in medical care, thanks to the incredible amount of practice that surgeons received during those four years. Experimentation during the war led to refinement afterward that laid the foundation for the practice of modern specialized medicine. The need for accurate weather forecasting led to the establishment of new weather stations that ultimately became the modern National Weather Service. The destruction of livestock during the war also fostered the development and professionalization of veterinary medicine, as the government, through the auspices of the Department of Agriculture (founded in 1862), began to study the extent and effect of various animal diseases. Finally, the destruction of landscapes in the east led the government to preserve landscapes in the west, like Yosemite and Yellowstone, and plant the seeds that became the National Park Service–which now (fittingly perhaps) maintains many of the nation’s larger Civil War battlefields.

There were negative legacies, too. Tens of thousands of soldiers returned home hopelessly addicted to opium (used as a painkiller during the war). The consumption of opium increased five-fold in some parts of the country after the war. The loss of land and labor in the South locked farmers, black and white, into debt peonage, as they were forced to grow the cash crop of cotton, which not only hurt farmers economically but also exacerbated already bad erosion of southern soils. The loss of so many hogs and the enactment of fencing laws, meant that not as many farmers could supplement their diets and incomes with livestock. Many southern states never recovered their hog populations until the advent of corporate hog farms in the latter half of the 20th century.

8) What can modern readers take away from the book that might help them better understand our relationship with the environment now?

A basic tenet of environmental history is that one cannot understand human actions apart from their place in the natural world. Yet we often think and act as if nature is an abstraction. Yes, we notice the weather and develop relationships with some animals, especially our pets, but for many Americans, nature doesn’t often matter. They fail to notice that it affects us on an everyday basis. Occasionally something jars us out of that patently arrogant assumption–a fire, a flood, a novel virus to which we have no immunity–but the tendency is to treat these as temporary interruptions in our human routines and to return to “normal” as soon as possible. We hope that by showing the role of the natural world in something as crucial to American history as the Civil War, we might encourage readers to think more deeply about our connections to nature and what those connections might portend for our future.

And we hope the book might encourage more scholars to look at the environmental consequences of other wars. Agent Orange in Vietnam, unexploded ordnance from World War I, and the burning of Iraqi oil fields after Operation Desert Storm are a few of the topics that have drawn attention from environmental historians. A host of others remain to be investigated.

9) Can you talk a little bit about your research and writing process as a team?

Before we were co-authors we were friends. And we trusted each other’s scholarship. Both of those are crucial to any effort of this type. For the most part, we were also able to put our academic egos aside in the interest of the greater good, that is turning out a book that neither of us could have managed on his own.

For the actual writing, we first reserved a library study room and brainstormed ideas for each chapter on a whiteboard. That allowed us to develop a basic outline. Since Judkin knew the war well, its chronology and strategies, we usually (with a couple of exceptions) began with him writing the first draft of a chapter. It established a foundation on which Tim would add some environmental layers. We then passed each chapter back and forth many times, each adding or subtracting, or suggesting new directions or rethinking ideas.

We worked in different ways: Judkin liked to put a lot of words on the page, knowing that everything would be revised, while Tim was more deliberate with each sentence. Since Tim was the sharper editor, he was able to take the drafts and revise and craft the language into smoother, flowing prose. Once a chapter was finished, we met again in the library and went over every sentence, editing along the way. Every collaboration is different, but we quickly found the writing groove that worked well for us.

In terms of research, we each were constantly digging into the literature or primary sources to explore new directions in what we were finding. Judkin rummaged through the major primary sources that all Civil War historians utilize as well as the war’s large secondary literature, while Tim tended to wander through science databases to learn more about the specific issues. However, this was truly a shared experience as we each contributed to both sides of the equation—it wasn’t just Judkin providing the quotes and Tim providing the science. For instance, Tim found some great material that helped us frame the opening of chapter 3 (at Gettysburg) and chapter 6 (at Saltville), while Judkin researched the geology of the Virginia peninsula and the nutrition of the armies. By the time we finished our collective fingerprints could be found on every chapter and nearly every line of prose.

What was your favorite source you worked with while writing the book?

Tim: I know it sounds macabre, but going in I knew little about the process of human decomposition, that is how dead bodies function in the natural world. Reading the science on that topic was fascinating, especially the various enzymes involved and the ways in which some organs, like the pancreas, literally consume themselves. I was also intrigued by the elaborate caskets, body bags, and other contraptions invented to slow down decomposition, especially those designed to mask or control the odor commonly called the scent of death.

Judkin: While the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion was probably one of the most helpful comprehensive collection of primary sources, and one that all Civil War historians utilize, I enjoyed digging into the role of horses in the war–discovering how relatively few there were in the country, how armies acquired them, tried to care for them, and the steep learning curve for armies, trying to create a functional cavalry arm is a incredibly short time frame. Most horses were not bred to be warhorses, and the men who joined the cavalry (especially in the North) were not very familiar with how to ride them properly. European armies devoted years to training cavalry soldiers; Americans had to do it in a few weeks. Europeans were not impressed. As one Dutch cavalry officer noted, “They never learn to ride, never can preserve their balance, but hang on the horse like a senseless lump” which wore the horses out very quickly.

Who, among the book’s cast of characters, did you come to appreciate better?

Tim: For me, it’s not any one individual, but rather the soldiers on both sides who endured such adverse conditions. Sickness, hunger, vermin, and foul weather–not to mention the fear of meeting an anonymous end on a battlefield–were the enlisted man’s constant companions. I’ve often heard the Civil War described as “an epic struggle,” but just figured that was a cliche. I’ll never look at it that way again.

Judkin: Most Civil War historians have a low opinion of Union General Benjamin Butler, and deservedly so. He was not a tactical mastermind by any stretch. But occasionally even bad generals get something right. It was fascinating to see how Butler accidentally stopped a disease outbreak in New Orleans. Many southerners expected a yellow fever epidemic to wipe out the Union soldiers, and it very well may have occurred. But Butler, erroneously believing that disease emanated from filth and noxious vapors, put people to work scouring the streets of New Orleans to clean up the city. As a result, he inadvertently prevented the establishment of the breeding grounds for the aedes aegypti mosquito, which actually carried yellow fever.

What’s a favorite sentence or passage you wrote?

Judkin’s favorite is in chapter 3: “The image of thousands of threadbare Confederate soldiers, reeking of excrement, bile, and body odor, squatting to defecate or bending over to vomit in the fields and woods lining the roads to Maryland lacks romance, but such were the hard realities of sustaining the southern army.”

Tim’s favorite is in chapter 5: “A fallen soldier might be dead, but once his rotten corpse became part of the natural world, it sustained a surprising array of life.”

What modern location do you like to visit that is associated with events in the book?

Judkin likes visiting the Seven Days battlefields outside of Richmond, and takes his summer military history class on a field trip there every other year. We both enjoyed visiting Saltville, Virginia, to research for chapter 6 as well. As a Civil War novice, Tim was pretty much “along for the ride” on these journeys, but especially enjoyed exploring the Malvern Hill and Wilderness sites.

What’s a question people haven’t asked you about this project that you wish they would?

Judkin offers this one: How does looking at a well-known event through the prism of the environment alter our understanding of it? I had taught the Civil War for a decade before we started this project, and I have learned a hell of a lot about the Civil War as a result of writing this book. I have literally changed every lecture on the war because of what I have learned in this process. Looking at an event through an environmental prism causes you to ask so many questions that perhaps had never occurred to you before. And that really opens the door for some exciting discoveries.

From Tim: “Why are co-authored books and articles so rare among historians?” I’m not completely sure, but my guess is that the reason lies in the rather antiquated way history departments decide on tenure and promotion. The goal of every beginning historian is to publish the monograph, the great piece of original research that “changes the field.” That doesn’t exactly encourage collaboration. And truth be told, we both wrote monographs and other “lone scholar” type books before moving to this project. So we didn’t risk much, career-wise. My hope is that this book might encourage more historians to work across their sub-disciplines or even with scholars from other fields as a way bringing fresh perspectives to their work. It worked out well for us.

As an ecologist and Civil War ancestor researcher, I appreciated this unique exploration of the war. Thanks