“The Irish spirit for the war is dead:” The Irish Brigade at Fredericksburg and the Battle’s Impact on New York’s Irish-American Community

ECW welcomes back guest author Abbi Smithmyer

Every year, thousands of visitors flock to the Fredericksburg Battlefield. As they walk along the sunken road, stand behind the stonewall, gaze into the windows of the Innis House, and walk through the National Cemetery atop Marye’s Heights, one of the most iconic stories of the historic battle is the gallant charge of the Irish Brigade. The doomed, yet heroic charge of the famous Irish unit has remained a dominating part of the historiographical narrative of the December 13th battle. While interesting, this narrative fails to acknowledge the overwhelming disillusionment among New York’s Irish community. Of the 1,200 men in the Irish Brigade who made the attack, 545 were killed, wounded or missing.[1] This large loss of Irish life, coupled with lack of acknowledgment by native-born Americans, left the Irish community feeling as though their sacrifice was unappreciated. Unlike today, Fredericksburg left a dark memory on many Irish families in the Union and greatly impacted ethnic morale.

While many initially considered Antietam a great Union victory, as time went on and the casualty reports circulated throughout the northern papers, the Lincoln administration realized it was not a miraculous success. This realization came after the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued, which meant the President needed a military victory to silence his opponents before it went into effect on January 1, 1863. Without a Union victory before the start of the new year, the already demoralized soldiers and civilians of the North would have little support for the continuation of a war now centered on the abolition of slavery. Lincoln’s need for a victory meant that the newly appointed general, Ambrose Burnside needed to move swiftly and fight a winter campaign, something almost unheard of in the nineteenth century. The Army of the Potomac was an army in turmoil when he took command and his troops doubted his ability to follow in the footsteps of their beloved commander, General George B. McClellan. However, Burnside moved quickly, marching his Army southward towards Richmond. To get to the Confederate capital, he needed to take his army across the Rappahannock River and through the city of Fredericksburg. Unfortunately for the newly appointed general, his army was delayed by the late arrival of pontoon boats, which forced him to fight the rebels who had weeks to prepare for the December battle.[2]

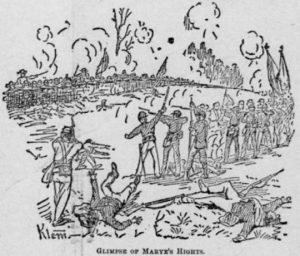

As with other battles fought in 1862, the Irish Brigade again showed their tenacity and bravery at Fredericksburg. On the morning of December 13, the brigade fell in along the banks of the Rappahannock River and waited their turn to advance against the Confederate defenses positioned atop Marye’s Heights, about a half-mile outside the colonial town. Here, men under Major General James Longstreet’s I Corps were in a superb defensive position in a sunken road bordered by a stonewall. The Confederates were dug in here, with rows of rifle pits behind them and artillery support from Colonel Edward Porter Alexander prepared to cause havoc for the charging Union soldiers. One soldier of the Irish Brigade was obviously worried as he confided to his chaplain saying, “Father, they are going to lead us over in front of those guns which we have seen placing, unhindered, for the past three weeks.”[3]

Around one o’clock, the Irish Brigade began their assault on Marye’s Heights. As they passed the dead and wounded Union soldiers from the previous assaults, their identity as United States soldiers took prominence. The Irishmen managed to maintain their formation as they confronted a storm of bullets, grapeshot, and canister, which inflicted horrifying casualties. Private William McClelland of the 88th New York wrote that “Up hill and forward over an open plain a quarter of a mile wide we rushed, the enemy firing with their rifles deadly volleys…[when] we were within thirty or forty yards of the rifle pits, we met dreadful showers of bullets from three lines of enemy, besides their enfilading fire. Our men were mowed down like grass before the scythe of the reaper.”[4] “This useless sacrifice of life was kept up all day on the 13th, and well into the night,” recalled John Dwyer of the 63rd New York Infantry.[5] “No pen can describe the horrors of this battle,” remembered George Nugent of the 69th New York Infantry. Recalling “the casualties were enormous. It was a living hell from which escape seemed scarcely possible.”[6] Of the thirteen Union assaults against the heights that day, the Irish Brigade is recognized for pushing the furthest. Although they reached within yards of the stonewall, the men failed to take the position and by the end of the afternoon, the shattered Brigade and the rest of the Union Army’s casualties were left on the field of battle. An Irish Brigade captain declared, “Oh! It was a terrible day. The destruction of life has been fearful, and nothing gained.”[7]

The United States Army suffered tremendously, as nearly 13,000 men became casualties, with the Irish Brigade bearing a heavy portion of the loss. Of those in the Irish Brigade who entered the battle of Fredericksburg, the 69th New York lost 16 of its 18 officers and 112 of the 210 men were killed, wounded, and missing.[8] The 88th New York suffered a fifty percent casualty rate, while the 63rd New York lost forty-four of its 162 men that went into battle. The 116th Pennsylvania lost most of its officers and men, while the 28th Massachusetts Infantry, which had just joined the brigade in the fall, lost 158 men on the field of battle.[9] Father William Corby, chaplain of the 88th New York, was horrified when he witnessed the suffering of his Irishmen, declaring, “the place into which Meagher’s brigade was sent was simply a slaughter-pen.”[10] Captain David Conyngham described the action at Fredericksburg as “a wholesome slaughter of human beings—sacrificed to the blind ambition and incapacity of some parties” rather than a battle.[11] A soldier of the 88th New York Infantry, expressed the somber situation the best when he wrote, “The battle of Fredericksburg should be written in letters of blood on the banners of the Irish Brigade.”[12]

As the most visible example of Irish arms in United States service, the Irish Brigade’s suffering at Fredericksburg played an influential role on ethnic morale and left Irish neighborhoods in New York infuriated. On December 27, 1862, the New York Irish American published a letter written by Captain William J. Nagle of the 88th New York to his father the day after the battle. “Irish blood and Irish bones cover that terrible field to-day,” Nagle wrote, saying, “we are slaughtered like sheep, and no result but defeat.”[13] One Irishman simply stated, “As for the remnant of the Brigade, they were the most dejected set of Irishmen you ever saw or heard of.”[14] When General Thomas Francis Meagher returned to New York in January for a high mass recognizing the sacrifices of the Irish Brigade, he found Irish disillusionment on the home front as well. Irish communities in New York read the newspapers and saw the lengthy casualty reports, which came only a few months after those from Antietam. Irish Americans at home mourned the loss of their husbands, fathers, and sons, and challenged the idea of sending more Irishmen into the ranks of the Union army. The Irish American warned General Meagher that recruitment of Irishmen would only work “if men can yet be found to volunteer in a war—[if] the conduct of which reflects anything but credit on those who have undertaken its management.”[15]

The disenchantment among Irish Americans in New York only grew stronger into one unified voice as the sacrifice and cost of the Irish Brigade seemed to go unnoticed and unappreciated by native-born Americans. In a letter published on January 17, 1863, by the Irish American, Colonel James Meehan of Corcoran’s Irish Legion angrily pointed out that they could not get an account of the Irish Brigade’s actions at Fredericksburg in any of the New York newspapers. Hinting at nativism, the letter stated, “Though we were certain that they fought well and bravely…yet we wished to have the particulars—every other brigade being particularized.”[16] Irish soldiers and civilians called for the removal of the Irish Brigade from the field until they could be recruited up to fighting strength. The Irish Brigade “is so small now that it is not fit to go into any further action unless it is recruited up,” wrote an Irish soldier.[17] With a similar belief, the most popular Irish newspaper in New York warned the War Department that, “To bring them into conflict with the enemy in their present condition, is an outrage on humanity of which we trust the government will not be guilty.”[18]

As anger grew among Irish-American communities at home in New York, Meagher pushed President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to grant special leave time for the Irish Brigade to rest and recruit its depleted ranks. Sometimes, Meagher’s requests went without response and at other times War Department officials explained that there were not enough troops in the field to grant the brigade’s leave request.[19] One soldier in the Irish Brigade wrote home to his mother, pointing to nativism as the cause for the men not receiving permission to be sent home. “We thought surely that our brigade was going home to New York” he said, “but we were kept back and would not be let go in account of we being Irish.”[20] As this news spread, Irish men and women in New York erupted with anger and accused the government of outright prejudice. An editor of the Irish American angrily reported, “it appears to me as if they were most anxious to blot out our race altogether….they seem not to recollect the fact that they are doing all in their power to demoralize the remnant of a magnificent brigade.”[21] When the War Department argued that the United States was in too precarious a position to grant whole brigades leaves of absence, Irish Americans pointed to units from other states that secured periods of rest. Capturing the mood, the Irish American argued, “If the Brigade were not so markedly and distinctively Irish, they would not have been treated with the positive injustice to which they have been exposed.”[22] Boston’s Irish newspaper the Pilot went even further by describing the feeling among Irish Americans when it cried, “the Irish spirit for the war is dead! Absolutely dead!”[23]

For increasing numbers of Irish Americans in New York and elsewhere, the cost of war and its changing goals no longer seemed worth the sacrifice. These individuals began to place their ethnic identity above their devotion to America. While some saw the war solely through their American patriotism, others who were recent immigrants, saw the need to view the conflict in terms of how it would benefit them as Irish men and women. As this reversal in Irish-American support occurred in the days and months following the tragic battle of Fredericksburg, native-born citizens became increasingly agitated with the ethnic group. Ultimately for the Irish, the devastating loss at Fredericksburg was a blow that weighed heavily on their devotion to the Union.

[1] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), ser. 1, vol. 21:129.

[2] Francis Augustín O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 4-6.

[3] Francis Augustín O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 121.

[4] New York Irish American, January 10, 1863.

[5] Major John Dwyer, 63rd New York Infantry, Address of John Dwyer at the 52nd Anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg held at the Union Square Hotel in New York City, December 12, 1914, Bound Volume 038-08, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Collections.

[6] Third Annual Report of the State Historian of the State of New York, 1897 (New York: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Company, 1898), 42.

[7] New York Irish American, December 27, 1862.

[8] William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (Albany, NY: Albany Publishing, 1889), 204.

[9] Francis Amasa Walker, History of the Second Army Corps in the Army of the Potomac (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1886), 192.

[10] William Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life: Three Years with the Irish Brigade in the Army of the Potomac, Lawrence Frederick Kohl, ed. (Chicago: La Monte, O’Donnell Printers, 1893), 132.

[11] David Power Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns (Glasgow: R & T Washbourne, 1866), 343.

[12] New York Irish American, January 10, 1863.

[13] New York Irish American, December 27, 1862.

[14] Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns, 350.

[15] New York Irish American, December 27, 1862.

[16] New York Irish American, January 17, 1863.

[17] Peter Welsh, Irish Green and Union Blue: The Civil War Letters of Peter Welsh, Color Sergeant, 28th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers, eds. Lawrence Frederick Kohl and Margaret Cossé Richard (New York: Fordham University Press, 1986), 40.

[18] New York Irish American, January 17, 1863.

[19] Susannah Ural Bruce, The Harp and the Eagle: Irish American Volunteers and the Union Army, 1861-1865 (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 153-155.

[20] Civil War Widows’ Pension of William Dwyer, 63rd New York Infantry, accessed at fold3.com, August 14, 2019.

[21] New York Irish American, January 17, 1863.

[22] New York Irish American, March 14, 1863.

[23] Boston Pilot, May 30, 1863.

Interesting angle I hadn’t seen before. Wonder if any of this resentment had an impact on the NY draft riots in1863?

Absolutely. Imagine you believe, not without cause, that you are being singled out as cannon fodder and then they introduce a measure that you can be drafted while the rich can buy themselves out of service

This is a completely normal feeling of alienation and failure of the majority society to honor the courage and sacrifice of an ethnic minority. No one the Irish Brigade after Fredericksburgh was never the same organization. A good, thought provoking essay. Thank you.

Nice essay.

Irish immigration to this country occurred during an intense wave of nativistic and anti-immigrant rhetoric. This was manifested by the Know-Nothing Party, which existed for years until they were absorbed into he Republican Party. The Irish were on the lowest rung of social order in the United States, just above slaves and equal with free Afro-Americans.The Irish were despised because they enjoyed alcohol and were Catholics, so their loyalty to the United States, could be questioned. I have a sign on the refrigerator which reads “Irish and Blacks need not apply” to remind me of the prejudices my Irish ancestors felt.

Father “Fair Catch” Corby in his book after the Civil War, related that the Irish Brigade stood at Antietam and Fredericksburg to show Protestant America that the Irish were loyal to the United States and were willing to die for freedom, and for their new Country.

Probably comparisons can be made between the Irish Brigade and their fighting ability, and those of the 442nd Infantry Regiment of World War 2. Made up of 2nd generation Japanese Americans, the 442nd is the mostly highly decorated unit in US military history, for its size….9486 Purple Hearts, 4000 Bronze Stars, and 21 Medals of Honor.

The difficulty with the conclusion in the author’s narrative is contained in the post itself. The Irish were seeking special permission to return home and refit. The Irish were not the only unit that had been decimated in the Fredericksburg blood bath. Coupled with the infamous Mud March, the appalling weather and outbreak of disease, the failure of proper rations and political infighting, and this was probably the nadir of the AOP. The Irish, like most immigrants, suffered from prejudice, particularly during times of economic depression. However, the greatest wave of No Nothingism had passed, devoured in the sectional wars. Indeed, one reason Lincoln had been nominated was to offset the nativist origins of some of the party chieftains, particularly Bates. The Democrats, partially rooted in the urban working centers, had always at least feigned an interest in the immigrants. The trauma the Irish had sustained back in their own land prior to emigration made them susceptible to seeing all setbacks as deliberate slights. Some were. Even to we Scallons.

Excellent essay!! There was a great amount of distrust of the government following Fredericksburg. Thomas Meagher was also losing some of his luster. The Irish community felt they were being used as “cannon fodder” by Lincoln and the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation only incensed the Irish even more. The Irish were willing to fight to save the Union, but they were not willing to fight and free slaves who, they felt, would head North and take their jobs from them. The draft in NYC in July of 1863 was the final event to ignite the powder keg of disgruntlement and thus ensued the deadliest riots in NYC history up to this day.

I get to brag, I taught Ms. Abbi history when she was in grade 8.