“I Confess That My Life at West Point Was Wretched”: O.O. Howard’s Plebe Year

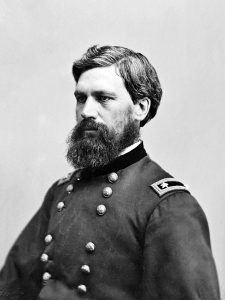

Had his cousin William been in better physical shape, O.O. Howard probably would have never gone to West Point. Otis, as his family called him throughout his life, was in his senior year at Bowdoin College in Maine when his uncle John, a congressman, wrote to him, “From what William writes me today, I am of [the] opinion that he will not be accepted at West Point.” Uncle John went on, “What I wish to know is whether in case he is not accepted, you would like to have me recommend you,” for the cadet’s position. Otis Howard, not yet twenty, hemmed and hawed before deciding that he would attend the United States Military Academy. Within the year, he was contemplating resignation.[1]

Howard arrived at West Point in the fall of 1850, part of the eventual Class of 1854. To mark his graduation from Bowdoin, Howard purchased a silk top hat and a walking cane, but on the advice of a friendly officer from his home district, Howard ditched the accessories before he got to the Academy. One historian still referred to him as, “priggish, self-righteous, and opinionated,” however. Perhaps that was where his troubles began.[2]

Or perhaps it was the fact that Howard shied away from the traditional vices found at West Point. Just days after arriving at the Academy, he wrote to his mother, “The influences here are not of the healthiest kind as far as concerns the moral character,” He continued, “I get neither real friendships nor sympathy. The few with whom I am acquainted most intimately wonder why with my education & my dislike for the coarse & profane, why I should come here. But I do not regret it yet.”[3]

Howard soon ran into troubles, though. A close family friend, Warren Lothrop, was a non-commissioned officer stationed at West Point. Howard visited his friend, but had not given thought to the army’s hierarchy and its dismissal of fraternization between officers and enlisted men. After repeated visits with Lothrop, Howard realized his fellow cadets were starting to turn their noses at him. Finally, the Academy’s Superintendent, Capt. B.R. Alden, took the young Mainer aside and explained that, “It will not do for you to recognize [Lothrop] in any social way.”[4] For Howard, it was strike two.

Strike three came from his fellow cadets, with two in particular. Cadet George W. Custis Lee, from Virginia (and Robert E. Lee’s son), and Cadet Henry L. Abbot, from Massachusetts, both challenged Howard for top marks. Howard remained neck and neck with the two in classes ranging from mathematics to foreign language. It drove the other two crazy with jealousy, and, like common schoolyard bullies, they formed cliques and drove Howard out.

“Mr Abbot & Mr Lee are now & shall be for the future on the most distant terms with me,” Howard wrote home in May, 1851. Expounding on Custis Lee, Howard said, “I had considered him one of the finest young men I had ever met, till all at once for some unknown reason he conceived a strong antipathy for me. . . I could attribute his conduct to nothing but jealousy.”[5]

Otis Howard was, in the parlance of the day, “cut.” Howard was accused of being an abolitionist, of hanging around other “cut” cadets, of visiting with enlisted men (Lothrop), and of purely going to Bible study to ingratiate himself with the professor of ethics, William Sprole. “I now saw that individuals who belonged to the small conspiracy passed me without recognition or took some other method of showing that my society was not desirable,” Howard remembered in his autobiography.[6] It all led him to declare, “I confess that my life at West Point was wretched.”[7]

Not all were against Howard, though. An unlikely friend appeared in the form of another Virginian, young J.E.B. Stuart. The two went to the controversial Bible study together, and took long walks along the grounds. “He spoke to me, he visited me, and we became warm friends,” Howard wrote years later, long after Stuart was dead. To an interviewer, Howard pronounced Stuart, “My best friend.”[8]

Stuart aside, Howard had to weather the storm of his first year and the continued ostracization. Beyond his attitude, beyond his academic standing, he had to contend with the pro-slavery faction of his fellow cadets. Howard himself admitted in his autobiography that he was not yet the ardent abolitionist that he would become. However, in the words of historian William McFeely, “There were many Southerners at West Point, and in the fifties the more ardent of these used ‘Abolitionist’ as a blanket term of derision covering any suggestion of opposition of slavery.” Howard certainly fit the bill there—He described himself, “to be somewhat of a Whig – somewhat of an abolitionist, rigid teetotaler &c.” His continued outspokenness regarding slavery, was enough to earn Howard the derision of the pro-slavery cadets.[9]

By the end of July, 1851, and as he neared the end of his first year at West Point, Howard was at a breaking point. He had gone through nearly an entire year of hardly anyone talking to him, and cadets like Lee and Abbot continued to spread rumors about him. At the end of the summer encampment, Howard wrote into a diary, “The insults, the slights of very many of my classmates, kept up & rendered so everything have had an unfavorable influence upon my sensitive nature.”[10]

Nearly caving to the pressure, he wrote a letter to his stepfather. “For what reason I cannot tell, but there certainly is a combination against me. . . in the hope that I may break some important regulation of this Academy, and receive a severe punishment, perhaps a dismissal.” Explaining the abuses, Howard wrote, “I can no longer bear [it]. I must either have justice done me or I must resign my warrant as Cadet. I cannot exhaust all the energies of my youth in a pursuit worse than useless. To live as I do now, the constant object of slight neglect and malice, I feel to be absolutely degrading.” He finally came to the point of writing his letter, “I wish you to write me your permission to resign. I may not use it, probably shall not be forced to, but I wish for justice & if I cannot obtain it, I shall have your permission as an instrument in my hands to fall back upon if necessary.”[11]

Here was the decisive moment of Howard’s life up to that point. He could resign, and go home to Maine to find other pursuits in life. But he never sent the letter. Rather, he went back to work. In the margins of the letter to his stepfather are mathematical equations; Howard did not quit but put his head down and determined to exceed. He was buoyed by a visit from his family, and he decided to not let the likes of Custis Lee or Henry Abbot dictate his future. He took advice from the Capt. Alden, the superintendent: “If I were in your place I would knock some man down.” As an old man, Howard remembered, “From that time on my friends had nothing to complain of from my want of spirit. I had some conflicts, some wounds, and was reasonably punished for breaking the regulations, and my demerits increased.” But he didn’t quit.[12]

Recognizing Custis Lee wished to excel as much as anyone else, Howard admitted, “He is a young man so talented, & generally so exemplary I cannot help respecting him.” As for Abbot, Howard simply stopped paying him any mind. “When I meet him he usually puts on airs; at which I cant help smiling sometimes but we never speak. I am sure I hold my head as high as his then, if not always.”[13]

Three years later, Howard would graduate fourth in the Class of 1854; Custis Lee was first, and Henry Abbot second. Howard, who had come so close to quitting in the summer of 1851, spent the next forty years in the uniform of his country. He had far more challenging tasks ahead, and while he did not always succeed at mastering those tasks, he never shirked. The lessons of his first year at West Point stuck with him to the end.

______________________________________________________________

[1] John Otis to O.O. Howard, 6/20/1850, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

[2] Emory M. Thomas, Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (New York: Harper & Row, 1986), 24; O.O. Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Volume 1 (New York: Baker & Taylor Company, 1907), 44, 47.

[3] OO Howard to Eliza Gilmore, 9/8/1850, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

[4] Howard, 51.

[5] O.O. Howard to Eliza Gilmore, 5/19/1851, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

[6] Howard, 52.

[7] Ibid., 52-53.

[8] Howard, 53; William B. Styple, editor, Generals in Bronze: Interviewing the Commanders of the Civil War (Kearny: Belle Grove Publishing Company, 2005), 176.

[9] Howard, 48; William S. McFeely, Yankee Stepfather: General O. O. Howard and the Freedmen (W.W. Norton, 1994), 32; O.O. Howard to Eliza Gilmore, 9/27/1851, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College; O.O. Howard to Eliza Gilmore, 4/11/1852, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

[10] O.O. Howard Diary, 7/27/1851, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

[11] O.O. Howard to John Gilmore, 7/27/1851, (unsent), O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

[12] Howard, 53.

[13] O.O. Howard to Eliza Gilmore, 9/27/1851, O.O. Howard Papers, Bowdoin College.

Well–I cried. Much of my personal studies have concerned essential differences between young men from the southern states and those from the North. I am sure that many will say I waste my time–people are people no matter what. Yet Howard seems like such a Yankee to me. I felt badly for him coming up against the ease and conviviality of southern men and feeling so alone. I will be reading from your sources. Thank you.

I enjoyed this personal account from O.O. The interactions of the West Pointers is very interesting.

Stuart deserves his statue back up in Richmond just as a monument to befriending Howard.

What an inspiring story. I love it how people from the past are still passing on lessons to us here in the present. Moral of the story: “Don’t quit and see what happens”. It’s intriguing that a man like Howard would find such a good friend in Stuart, given their personalities and values. Wonderful stuff. Thank you for sharing!