“To Laugh in One Hand And Cry in the Other”: W.B. Higginbotham & the Black Community in Civil War Rome

ECW welcomes back David T. Dixon

Wm. Higginbotham, a well-known free man of color, also returned on Saturday morning. He reached Manassas on the morning of the battle, but was denied the privilege of taking a gun and falling into the ranks. He then assisted in removing the dead and wounded, amid a shower of balls that fell around. Such deeds are highly meritorious and deserve much credit.

Editor, Rome Weekly Courier, August 9, 1861

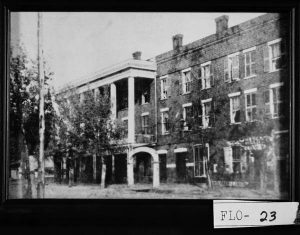

In the aftermath of the first significant Confederate victory of the Civil War, the press in Rome, Georgia, attempted to create the impression that the entire community, including black men like William Barton Higginbotham, was behind the new government, and eager to fight the “Lincolnites.” The truth was quite different. Higginbotham, a prosperous saloon operator at Rome’s Choice House hotel since the early 1850s, did not go to Virginia imbued with a sense of patriotism for the new Confederate nation. He went to free his children.

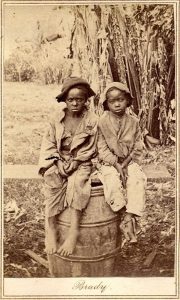

Higginbotham’s wife and children were the slaves of Dr. Homer V. M. Miller, a surgeon in the 8th Georgia Regiment. Dr. Miller maintained that he would only sell Higginbotham’s children to their father if this proud black man would serve as Miller’s personal servant on the battlefield. Higginbotham agreed and purchased his children in 1862. He was not allowed to purchase his wife.[1]

Higginbotham was an unusual black man in antebellum Georgia. Born free in Virginia in 1817, he was living in eastern Mississippi when he removed to the new settlement at Rome in 1845. By 1860, he had amassed a personal estate worth more than $10,000, and claimed to have loans of nearly twice that amount due to him.[2]

Higginbotham’s wealth placed him among the upper tier of Rome businessmen. “I was sort of a privileged character here at first,” he boasted, “and had some influence with the rebels.” On the day of the 1861 election of representatives to the secession convention, Higginbotham maintained that he changed some white voters’ minds towards supporting the Union ticket.

Even if his political influence was not as great as he was eager to claim, Higginbotham’s prominence in Rome’s business community made him an important symbol to other blacks in the county. Dr. Miller’s secret bargain was carefully crafted to use this black leader as a tool, not only to suggest Rome’s Confederate solidarity, but also to help dispel persistent fears of a slave uprising in the area. The agreement may not have been as one-sided as it seems today. Higginbotham was an abolitionist and could use his money, influence, and even the feigned appearance of loyalty to protect himself from the most violent secessionists and keep himself and his family safe in dangerous circumstances.[3] It was a precarious juggling act. “I know we had to laugh in one hand and cry in the other,” Higginbotham remembered, “when the Yankees were whipped or when the rebels were whipped.” Higginbotham’s color protected him from serving a Confederate cause he did not believe in. His freedom to move about and communicate with enslaved blacks during the war helped to sustain a black community that became even more threatened during such uncertain times.[4]

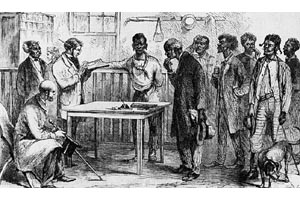

For the vast majority of enslaved and free blacks, the Federal occupation presented them with their first formal opportunity to aid the Union cause. In July 1864, a new Union regiment named the 44th Colored Infantry moved its headquarters to Rome and immediately sent recruiters into the countryside. The response was overwhelming. In a short time, more than 800 fugitive slaves had been recruited from farms and plantations across north Georgia and Alabama. The new recruits proved valuable in leading Sherman’s army to the most productive sources of produce and livestock for his hungry soldiers. General George H. Thomas reported that the desertion rate among black soldiers such as these was surprisingly low, considering the fact that the ex-slaves were often cheated by bounty agents and mistreated by their white commanders.[5]

Despite the support they rendered to the Union cause, many Floyd County blacks suffered depredations from both sides during the war. During the Federal occupation of Rome in 1864, the army used most public buildings for hospitals, warehouses and other military purposes. All the churches in town suffered some damage during this period, but the black-owned Methodist church was the only church in Rome demolished by the Federals, who built a fortification on the site.

As war enveloped Floyd County, free blacks like Higginbotham faced increased pressure from the community. Rome’s few free blacks no longer enjoyed a relatively secure status by 1864. The editor of the Rome Weekly Courier had certainly changed his attitude towards Higginbotham from gratitude to resentment in two-and-a-half years:

“It seems that free men of color have got to take a small part in the relief of the country as teamsters, laborers, &c. Higginbotham and Billy Barrett, the barber, were enrolled by Captain Gibbett, for service in the Nitre Bureau Department. These “gemmen of color” have made quite smug little fortunes since the war commenced, and it is no more than right, that they should do something for the government that protects them.”

What had not changed was the desire of the Courier’s editor to alter appearances in order to influence public opinion. Higginbotham was hardly thriving in the wartime economy. He had made numerous loans in Confederate currency, most of which would never be repaid. He and Barrett were conscripted, under orders to be taken “dead or alive”, and were only relieved from their forced service by the Federal occupation of Rome. [6]

Higginbotham’s property, like much commercial property in Rome, was damaged by the Union army during the occupation, and particularly upon the departure of Sherman’s troops in November. A gang of outlaws and Confederate deserters led by Jack Colquitt soon moved in and committed depredations on rebels, Union men, women and children with no regard for politics or religion. Remembering these tragic events years later, Higginbotham remained cautious. “To tell half of what I know,” he warned, “I could not live here 24 hours.” Like many of his white Unionist neighbors, Higginbotham felt even less secure after the war ended, since his Confederate neighbors would harbor resentment towards Union men and blacks for generations to come.

Higginbotham used his money, position, and influence in the black and white communities to do what he could for the Union cause, while retaining his principal loyalty to his family. In this respect, his experience was not unlike many of his white Unionist neighbors, who tried to balance political principles with the need to survive.

In 1867, General John Pope, military governor of Georgia, appointed Higginbotham and about 46 other blacks as district registrars for the upcoming election to the Georgia constitutional convention. Higginbotham organized the “colored” Union League in northwest Georgia in 1868 and served on the state’s Republican Central Committee. In 1872, he attended the Philadelphia convention as an at-large delegate from Georgia and was the district delegate to the 1876 and 1880 Republican national conventions. He must have been proud to see to see his son Archia attend Howard University’s new medical college and become a physician. William B. Higginbotham died at his home in Rome on December, 16, 1881.

Despite their accomplishments, Higginbotham and others could do little to stem an emerging tide of virulent racism that threatened every black man in the area. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed a relatively free reign throughout area, led by local notables such as retired lawyer and nationally known satirist Charles H. Smith a/k/a Bill Arp, and excused or tolerated by leading Union men, such as Augustus R. Wright.[7]

Blacks in Floyd County lived in fear at a time when they should have been protected by the government that they had risked their lives and property to support. In the four years following the war, the Rome District Freedman’s Bureau reported 31 separate instances of white on black murder or assault with intent to kill.

Although Floyd County’s blacks had no real political or social standing, they made a small but important contribution to Unionist resistance during the Civil War. Afterwards, their black faces were a constant and painful reminder to white ex-Rebels, of a brutal war that changed race relations in their society forever. While some white Union men would eventually regain the trust and acceptance of their neighbors, blacks confronted a persistent racial animosity that could not be as easily erased.[8]

————

David T. Dixon is the author of The Lost Gettysburg Address. His biography of German revolutionary and Union general August Willich will be published in September 2020 by The University of Tennessee Press.

Sources & Notes:

[1] Claim #1498. Peter M. Sheibley, Floyd County, 1878. SCC. Testimony of William B. Higginbotham. File now in USCC, docket #4997. Higginbotham’s allowed claim (#3650, 1872), like about 2000 others, was destroyed by mistake; but his testimony survives in at least ten other claims. He is also listed as a “prominent Union man,” in response to interrogatory question number 61, in at least twenty claims.

[2] There were only thirteen free black residents enumerated in the 1860 Federal Census of Floyd County, Georgia. Loren Schweninger found that only about one in sixty free blacks in the South owned property worth in excess of $2000. With a taxable estate of $10,000, Higginbotham ranked number thirty-five out of ninety-six Rome merchants and businessmen. See Loren Schweninger, Black Property Owners in the South, 1790-1915 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 100-141.

[3] Claim #1498, Peter M. Sheibley, Floyd County, 1878. SCC. Testimony of William B. Higginbotham. File now in USCC, docket #4997. For rumors of slave uprisings in Floyd County, Georgia in 1860, see Rome Tri-Weekly Courier, August 9, 14, 21, 23; September 11,14, 1860. A vigilance committee investigated the rumors and found them to be groundless, although a confession was exacted from the “guilty’ slave, whose punishment was freedom and a promise to leave the state. See Rebecca Latimer Felton, Country Life in the Days of My Youth (Atlanta: Index Printing Company, 1919), 87.

[4] Claim #15110. William Payne, Floyd County, 1879. SCC. Testimony of William B. Higginbotham. Claim # 1498, Peter M. Sheibley, Floyd County, 1878. SCC. Testimony of William G. Higginbotham. File now in USCC, docket #4997. Higginbotham’s claims about his nephew’s education and military service are confirmed in several other sources. Thompson was enrolled in Oberlin College’s Preparatory Department for one year, 1860-61, where he was trained to become a teacher, according to Tammy L. Martin of the Oberlin College Archives. William Thompson appears on the muster rolls of the 10th Ohio Cavalry, according to the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Search System, accessed January 27, 2003 at http:www.itd.nps.gov/cwss.

[5] Robert S. Davis, Jr., “White and Black in Blue: The Recruitment of Federal Units in Civil War North Georgia,” Georgia Historical Quarterly vol. LXXXV, No. 3, 354-357. The commander of the Forty-fourth USCT, the German-born Lewis Johnson, was threatened with death by one of his men “if he did not stop kicking his soldiers,” according to Davis.

[6] Rome Tri-Weekly Courier, February 11, 1864.

[7] Claim #1498, Peter Sheibley, Floyd County, 1878. SCC. Testimony of William B. Higginbotham. File now in USCC, docket #4997. CIS, v. 2, n. 41, pt.6, 43-63, 88-149. Peter Sheibley, in his testimony to the Congressional Committee investigating the Ku Klux Klan, accuses Wright and other local leaders of not using their influence to discourage the terrorist group from operating in the county. Wright was placed in the unusual position of defending several Klan members, who had been accused of murder and denied the right of habeas corpus by military authorities.

[8] Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Georgia, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1869, RG 105, reel 32 (microfilm), accessed January 27, 2003, via internet at http://freedmensbureau.com/georgia/gaoutrages4.htm.

Articles such as this always leave me with a strong since of doubt regarding the obvious attempt to impose a pro-Union spin. Here is a black man who has risen to prominence within deep South society. Yet we are led to believe that he had no sense of loyalty to home and State? He chose to remain in the deep South, amass what in that time was a small fortune, all while longing to purchase his wife and children, but waits until the war to travel to Virginia feigning support for the CS cause? Sorry, but the spun does not smell right!

It sounds to me that he, like the majority of blacks both slave and free, remained loyal to his Southland and went to Virginia to do his part for the cause. This is what the preponderance of primary sources reveal about the black mindset in the South at the beginning of the war. And while there in harms way doing his duty, he decided to secure freedom for his family, an otherwise odd time to make such and effort. If anything is to be doubted it is not the newspaper account, but rather the later testimonies secured during Union occupation. At that time it was common for Southern blacks to be duped into allegiance to the Republican Party, which later proved to be an attempt to use them as political pawns.

In a time when the ideals of human liberty were in their infancy, and civil rights movements yet to develop, it is understandable how blacks could support their society in which they were subordinate. It was a time of less ideological concerns and more a time of survival when the average person Of all races lived on less than a dollar a day in our current currency values.

This is why a member of the USCT could state when asked why blacks did not revolt during the war:

“That the negroes did not revolt is one of the incomprehensible features of our Civil War. Every chance for success was theirs, nor were they ignorant of their opportunity for striking an effectual and crushing blow against their oppressors. Why was it not done? Several potent causes combined to render any widespread insurrection at that time impossible. There was in the first place a genuine affection for the white race, implanted in hundreds of thousands of negroes by amalgamation, there was, in no less degree, a race love created by the foster parental relations which negro women sustained toward white children; there was also a genuine desire on the part of the negro men to discharge worthy the duties with which they were entrusted by their absent masters. But the supreme and all-pervading influence which restrained them was rooted in their religious convictions; for the slave negro, unlike the modern freedman, was a being in whom religious fervor was intensely and over-whelmingly manifest.” William Hannibal Thomas, 5th United States Colored Troops. The American Negro, published 1901.

Even an abolitionist who toured the antebellum South could state:

“I am struck with the close cohabitation and association of black and white. Negro women are carrying black and white babies together in their arms; black and white children are playing together. They all talked and laughed together; and the girls munched confectionary out of the same paper, with a familiarity and closeness of intimacy that would have been noticed with astonishment, if not manifest displeasure, in almost any chance company of the North.” Frederick Olmsted.

I respectfully but strongly disagree with your point of view which seems to be rooted in Lost Cause mythology of the happy slave and the benevolent master trope. Confederate newspapers spun their stories as partisan political organs as most all 19rh century papers were Noth and South. Testimony from the Southern Claims Commission and US Court of Claims was subject to a very high standard of investigation and proof and the overwhelming majority of claims were either rejected put of hand or greatly reduced after a thorough examination. To suggest that most Blacks free and enslaved supported the Confederacy just does not stand up to any rigorous examination of the available primary sources. In fact, they suggest just the opposite.

What a great post. Thanks!

Thanks TK