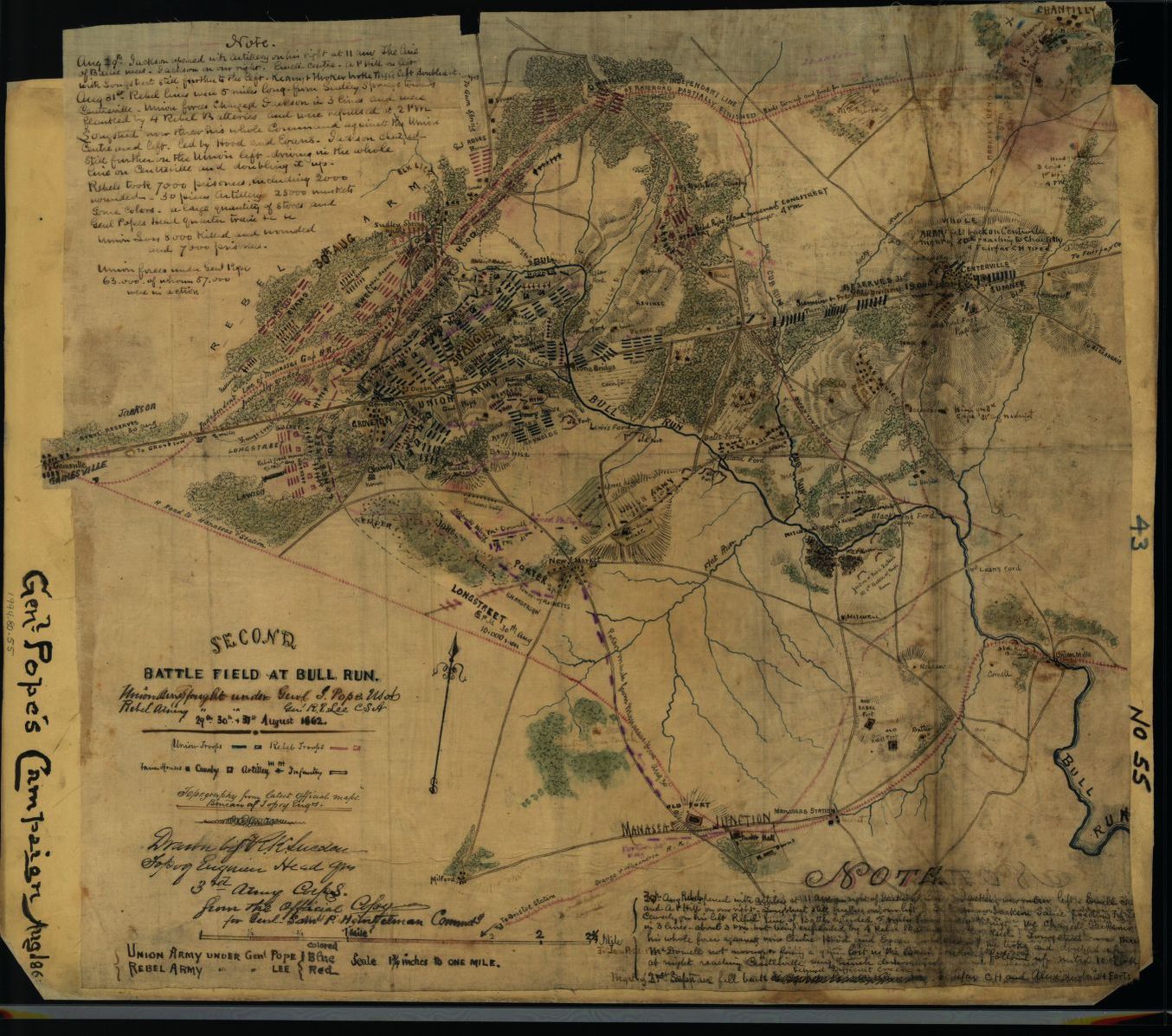

Assessing the Enemy: James Longstreet and John Pope at Second Bull Run

Union general John Pope’s decision-making during the campaign of Second Bull Run has been justly scrutinized by historians and armchair generals alike. In large part this scrutiny has stemmed from Pope’s bombast upon his arrival in Virginia and his failure to back up his “headquarters in the saddle,” “only seen the backs of our enemies,” proclamation with a substantial battlefield result. Pope’s contemporaries gleefully took part in lambasting the Illinois-born, West Point graduate—among them Edward Porter Alexander, who called Pope a “blatherskite” in his personal memoirs. The index to Alexander’s Fighting For the Confederacy (UNC Press, 1989) includes the entry “Pope, John; EPA makes fun of” as if to underscore the degree to which Pope was a common subject of ridicule after the summer of 1862.

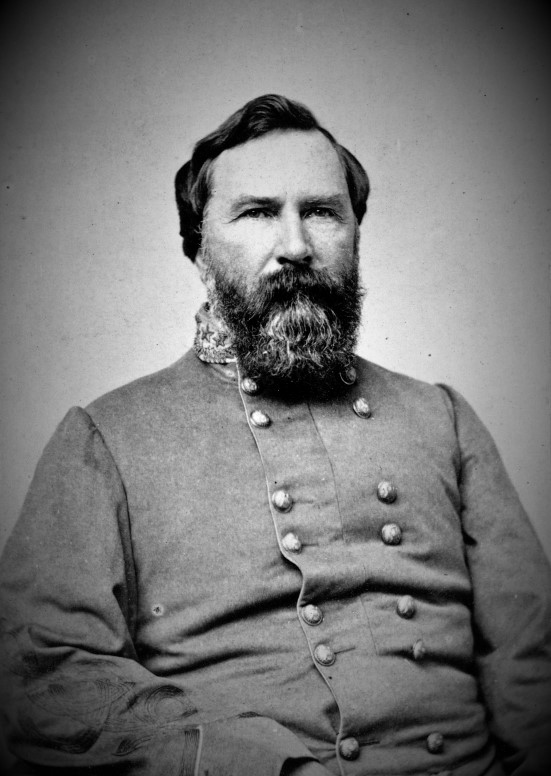

Though Pope remains a punchline for many modern historians, there are a few accounts of the battle and campaign of Second Bull Run that attempt to give Pope some credit for his efforts—and one such source might, on the surface, seem surprising. Unlike his chief cannoneer, Confederate general James Longstreet offered Pope a remarkably even-handed treatment in his post-war memoirs. Longstreet and Pope had been West Point classmates, where Pope clearly outpaced third-from-bottom Longstreet in their studies. By the time they met on the plains of Manassas, however, Longstreet had soundly demonstrated his leadership abilities, whereas Pope commanded an army that had little reason to place their confidence in him.

At the end of his summary of the events of the campaign of Second Bull Run, Longstreet wrote the following:

The conduct of General Pope’s army after his receipt of the captured despatch was good, especially his plans and orders for the 27th and 28th. The error was his failure to ride with his working columns on the 28th, to look after and conduct their operations. He left them in the hands of the officer who lost the first battle of Manassas. His orders of the 28th for General McDowell to change direction and march for Centreville were received at 3.15 p.m. Had they been promptly executed, the commands, King’s division, Sigel’s corps, and Reynolds’s division, should have found Jackson by four o’clock. As it was, only the brigades of Gibbon and Doubleday were found passing by Jackson’s position after sunset, when he advanced against them in battle. He reported it ‘sanguinary.’ With the entire division of King and that of Reynolds, with Sigel’s corps, it is possible that Pope’s campaign would have brought other important results. On the 29th he was still away from the active part of his field, and in consequence failed to have correct advice of the time of my arrival, and quite ignored the column under R. H. Anderson approaching on the Warrenton turnpike. On the 30th he was misled by reports of his officers and others to believe that the Confederates were in retreat, and planned his movements upon false premises.

The only thing Longstreet seemed willing to condemn his Federal adversary for was his failure to come closer to the battlefront during the first and second day’s fighting, while letting Pope entirely off the hook due to being “misled” by his officers about the Confederate retreat on August 30. Longstreet was more willing to condemn the actions of his fellow Confederates during the campaign, particularly A.P. Hill and Fitzhugh Lee, than he was willing to criticize Pope.

One explanation for Longstreet’s comments is that he could judge Pope’s experience from the position of an army commander, unlike many of his contemporaries. Longstreet understood the complicated politics of high command better than most of Pope’s critics—and he may have factored this into his judgment of the Federal officer’s conduct during the battle. Longstreet repeatedly noted that Pope had received very little support from his subordinate officers during the Manassas campaign, so much so that their inaction crippled the Union effort to defeat the army of Northern Virginia. Longstreet understood the commander/subordinate relationship on an intimate level. Even though he was probably Robert E. Lee’s most-trusted subordinate, Longstreet did not always agree with his commander’s decisions and, in 1863, requested a transfer out of the Army of Northern Virginia. After experiencing the disfunction of the Army of Tennessee and failing to distinguish himself in several small battles in the West, however, the Georgian sought a return to the Eastern Theater and made a critical difference at the battle of the Wilderness—where his troops prevented the collapse of the Confederate right flank on May 6.

Longstreet’s comments on Pope are also worth considering as a political statement. Longstreet’s memoirs are an example of how postwar politics could change how participants described Civil War events. By the time Longstreet published From Manassas to Appomattox (1896) he had already been identified by a cadre of Lost Cause writers as the scapegoat for the defeat of the Confederacy. Longstreet’s ultimate betrayal, however, was his declaration of allegiance to the Republican Party and his close relationship to the Ulysses S. Grant presidential administration. His memoirs, as a result, are not without bias toward many of the men who had branded him a pariah.

Therefore, Longstreet’s treatment of Pope may well have been influenced by the latter’s own affiliation with the Republican Party during the war. Unlike most Regular Army officers, who professed to be apolitical, Pope openly embraced the Lincoln administration’s goal of waging a harder war against the Confederates in the summer of 1862 than George McClellan had managed until that point in the war. It should be noted that Longstreet did express disapproval of Pope’s embrace of a harder war, however, writing that “the exigencies of war did not demand some of the harsh measures that he promulgated.”

Both of the explanations offered above are speculative but offer food for thought on the anniversary of the battle of Second Bull Run. Juxtaposing James Longstreet’s account of John Pope’s leadership against a wide array of derogatory reports does not redeem Pope’s reputation or prove that Pope should not be blamed for the Union defeat at Second Bull Run, but it does suggest that Civil War battles and campaigns were understood and judged on multiple levels by participants, who lived political lives and voraciously defended their own reputations in print. Still, I am inclined to give some weight to James Longstreet’s point-of-view on Pope, because he possessed a perspective and experience that few modern readers can fully understand.

For those of us who grew up around the time of the centennial or not long after, Pope’s reputation has been destroyed by what Bruce Catherine wrote about him. This is unfortunate because Bruce Catton was not a real historian. He didn’t even do his own research, which was done by Pete long. He was a newspaper reporter who happened to be a very good writer.

In Missouri court performed well in December 18 61 and destroyed a Missouri guard camp and captured hundreds of prisoners. He captured island number 10 along the Mississippi with thousands of prisoners. In other words he was a successful general, just like Grant. In my opinion he anybody would’ve lost Second Manassas campaign, given the generals under pope’s command

Bryce

In many ways, Pope was two years too early. In the summer of 1862, Pope advocated for a harsher way of war against the Southern people and Confederate cause, which was very different from the more conservative approach adopted by McClellan and many of the senior leadership in the Army of the Potomac at the time. This harsher approach was eventually adopted by Grant and Sherman, a strategy that eventually won the war. However, Pope’s abrasive personality, vanity, and ego–and most importantly–lack of military successes in Virginia doomed him from the start.