“Praise the Lord and Admiral Porter”: Running the Vicksburg Batteries

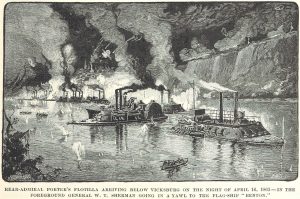

“We still live,” wrote Lieutenant Elias Smith of the USS Lafayette. “The whole gunboat fleet passed the Vicksburg batteries on Thursday night [April 16, 1863], without receiving material damage. All praise to the Lord and Admiral Porter.” As far as he knew, no Union lives had been lost; about a dozen were wounded, two seriously out of some two thousand men.

The U. S. Navy now had six ironclads, one wooden gunboat, and two troop transports in the river below the city. “How we escaped the firing ordeal as well as we did, is a mystery to us all. We were under fire for over an hour : and such fire! Earthquakes, thunder and volcanoes, hailstones and coals of fire ; New York conflagrations and Fourth of July pyrotechnics—they were nothing to it.”

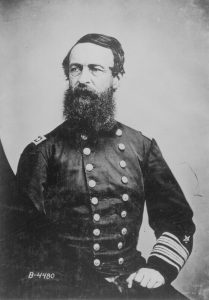

Smith’s observations were recorded in letters to friends and then published in the New York Times. The ironclad ram Lafayette—converted from a 280-foot sidewheel steamer—was a mainstay of Rear Admiral David D. Porter’s Mississippi River Squadron supporting Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in his campaign to take the Gibraltar of the West with the Army of the Tennessee.

The admiral and the general made a powerful team, melding maritime mobility and firepower with hard fighting on land. It had been a long slog, however. In late December 1862, Grant sent Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman downriver with a major amphibious force landing at Chickasaw Bayou northwest of Vicksburg only to be repulsed with heavy casualties.

Porter’s attempt to send gunboats up the Yazoo River and outflank the Confederate army facing Grant also failed, losing the ironclad USS Cairo to a Rebel torpedo—the first ship to be sunk by an electronic explosive device detonated remotely by hand.

During the winter and spring of 1862/63, Grant and Porter conducted a series of intense operations to outflank the city from north and east by digging canals, blowing up levees, flooding the Mississippi Delta, and pushing ironclads, gunboats, and transports through tiny, choked, and sluggish channels and swamps. All fruitless.

Grant’s final option was to march the army through the swamps down the west bank of the Mississippi, cross south of and get behind Vicksburg.

Admiral Porter would have to sneak his gunboats and fragile transports downriver past powerful and plentiful enemy batteries on the bluffs with enough vessels surviving to suppress opposition and get the army safely back across the Big Muddy.

Porter assumed this was a one-way, one-time run down; it would be suicidal to creep back up against strong current. If the navy failed, the Army of the Tennessee could be trapped on the wrong side.

It had been unthinkable in previous centuries for delicate wood and canvas men-of-war—dependent on fickle wind and armed with smaller weapons—to take on shore emplacements. Steam, iron, and increasingly powerful naval artillery had evened the odds between ship and shore. Ironclads were still vulnerable, however, especially to plunging shot.

The Union navy first successfully ran Rebel batteries at Island Number 10 upriver just the previous month, but only with two ironclads (and no transports) against less formidable batteries on low sand banks.

At about 9:30 p.m. on a clear, moonless night, Lafayette slipped her moorings. The wooden gunboat USS General Price and a heavily laden coal barge were lashed alongside to starboard where Lafayette’s armored casemate would at least partially shield them.

Just ahead of Lafayette was the big ironclad USS Benton, lead ship in the column with Admiral Porter aboard; the rest of the squadron followed. In the swirling river, the cumbersome Benton “persistently refused to point her head down stream,” continued Smith. “It was an hour later before the fleet were under way in her wake.”

Porter recalled: “We started down the Mississippi as quietly as possible, drifting with the current. Dogs and crowing hens were left behind.” Engines silent. Chains, cotton and hay bales, and logs piled along the decks provided additional protection.

A grand ball was to be held in the city that night; the admiral hoped “sounds of revelry” would mask their approach. “As I looked back at the long line I could compare them only to so many phantom vessels. Not a light was to be seen nor a sound heard throughout the fleet.”

Benton’s low, dark shadow crept around the point below the heights looming up 280 feet. “We will, no doubt, slip by unnoticed,” The admiral remarked to the ship’s captain, “the rebels seem to keep a very poor watch.”

Lafayette’s men silently stood to their weapons. Portside guns—9” and 11” Dahlgren smoothbores and a 100-pounder rifle—were ready, some at decreased elevation against lower Rebel emplacements, others elevated to strike middle and upper tiers.

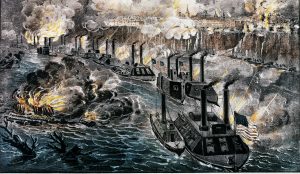

“The whole heavens were suddenly illuminated,” wrote Smith. “The lurid flames, as they shot up from the opposite shore, almost to mid heavens, converted the star-lit night into the brightness of noonday.” On the west bank, a railroad station, outbuildings, and prepositioned barrels of tar burst into flames, backlighting the fleet.

“We had not surprised them in the least,” noted Porter. “The upper fort opened its heavy guns upon the Benton, the shot rattling against her sides like hail….” But the blistering deluge made little impression on four inches of iron plating over forty inches of oak. “There being no longer any concealment possible, we stood to our guns and returned the enemy’s fire.

“Every fort and hill-top vomited forth shot and shell, many of the latter bursting in the air and doing no damage, but adding to the grandeur of the scene. As fast as our vessels came within range of the forts they opened their broadsides, and soon put a stop to any revelry that might be going on in Vicksburg.”

“At 11.20, the first shots greeted us from the batteries,” continued Smith. “The ‘Lafayette’ seemed to attract particular attention.” Tall chimneys and wheelhouse with a steamer alongside made her a good mark, “two birds with one stone.”

“Standing there amidst that silent group of rough but earnest men, periling their lives for their country, I thought of the kindness of our ‘dear Southern Brethren,’ as shot after shot swept over us with the scream of tigers eager for prey….

“Five hundred, perhaps a thousand, guns were discharged, but not more than one in ten struck, or did any damage to the fleet. They mostly went over…. In such a case, it was hard to ‘turn the other cheek ;’ in fact, it was more satisfactory to give than to receive.”

The Union column hugged the east bank to get under the line of fire, so close they could hear Rebel gunners shouting orders while shells zinged overhead.

Through open gun ports, Lieutenant Smith had a good view down enemy barrels, “which now flashed like a thunder-storm along the river as far as the eye could see ; but the incessant splatter of rifle balls, the spray from falling shot, the thunder of steel-pointed projectiles upon our sides, did not incline one to take a very protracted view of the scenery.”

Lafayette’s gunners got off a few discharges of grape, shrapnel, and percussion shell “in the very teeth of the Confederate batteries…. At each round the rebel artillery-men gave a shout, which seemed surprisingly near.” The ironclad wafted by not one hundred yards from Vicksburg wharves.

Lafayette became almost unmanageable, swinging in river eddies until she was “looking the batteries in the face.” Roiling gun smoke and the glare of burning buildings blinded the pilot. Bursting shells singed his hair but left him unhurt.

“The enemy, supposing we were disabled, set up a fiendish yell of triumph. We soon, however, backed round, and once more presented our broadside to them, and slowly drifted past, as if in contempt of their impotent efforts.” Shells sank the barge, “thus relieving us of one great obstacle to our movements.”

Wrought iron and steel-pointed missiles, 18-24 inches long, 6 to 8 inches in diameter, and about 100 pounds “were thrown by some of the heaviest rifle guns known to modern warfare,” continued Smith. “Nine shots struck the ship, and several of them penetrated the casemates, making large holes and scattering their fragments, and that of the wood-work….”

Lafayette’s armor was 2.5” of plate and 2” of India rubber (which proved useless) over 3” of oak plank, but the armor thinned to 1” plate and 1” rubber aft where most shots came through.

One round smashed through the pilothouse just missing the pilot. A 100-pounder skimmed over the boiler, obliterated a wood partition, and showered wood chips over Lafayette’s captain. Another passed through the paddlewheel housing, clipped the crank arm, and buried itself two feet into solid shaft supporting timber.

Smith’s stateroom was wrecked. He found his mattress sacking tuned to pulp amongst two bushels of corn shucks—finely ground—along with piles of pine chips, the ruin of a straw hat, blankets and clothing, “all covered with the debris of the room, which had been most elegantly ventilated.” And yet not one of the two hundred crewmen received a scratch.

On Benton, a gunner had his leg taken off; another crewman was wounded by a rifle ball through a gun port. Down the line, the transport Henry Clay was hit hard, recorded Admiral Porter, but “the courageous pilot…stood at his post and, with his vessel all ablaze, attempted to run past the fleet.” Men jumped into the water while the vessel floated until she burned up. The pilot was rescued.

Blazing cotton-bales blanketed the river, “looking like a thousand lamps.” Superstructure of the Forest Queen was nearly cut in two but she made it through in repairable condition. The other transport, Silver Wave, suffered minor damage.

“The enemy’s artillery fire was not much to boast of,” concluded the admiral, “considering that they had over a hundred guns firing at us as we drifted down stream in such close order that it would seem to have been impossible to miss us.

“The sight was a grand one, and I stood on deck admiring it, while the captain fought his vessel and the pilot steered her through fire and smoke as coolly as if he was performing an everyday duty. The Vicksburgers must have been disappointed when they saw us get by their batteries with so little damage.

“We suffered most from the musketry fire. The soldiers lined the levee and fired into our port-holes, -wounding our men, for we were not more than twenty yards from the shore. Once only the fleet got into a little disorder, owing to the thick smoke which hung over the river, but the commanding officers, adhering to their orders ‘to drift only,’ got safely out of the difficulty.”

On the night of April 22, six more transports loaded with supplies made the run with little damage. Then under cover of naval artillery, General Grant ferried his army across the river, surrounded and laid siege to Vicksburg, which surrendered on July 4, 1863.

It was one of the most brilliant campaigns of the war, at least as important as the simultaneous victory at Gettysburg. Admiral Porter and the Mississippi River Squadron transported the army, controlled the river, blockaded the city from the west, and provided continuous heavy shore bombardment.

Sources:

Admiral Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1885), 175-177.

H. Walke, Naval Scenes and Reminiscences of the Civil War in the United States, on the Southern and Western Waters During the Years 1861, 1862 and 1863 with the History of that Period (New York: F. R. Reed & Company, 1877), 353-359.

Great account. It is impossible to understate the importance of this event for both sides.

I agree that it is a great account. Without the cooperation of the army and navy in the western theater the war in the west could not have been won. Much praise to Grant and Porter for putting aside the usual rivalries between the two branches and keeping focus on the larger picture.

I’ll be honest, when I read the title, my brain filled in “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition”, haha. Wonderful post! Good stuff to know before a trip to Vicksburg. Thank you!

Why isn’t this a movie??