Observing the Hanging Hour: John Brown’s Death 161 Years Ago Today

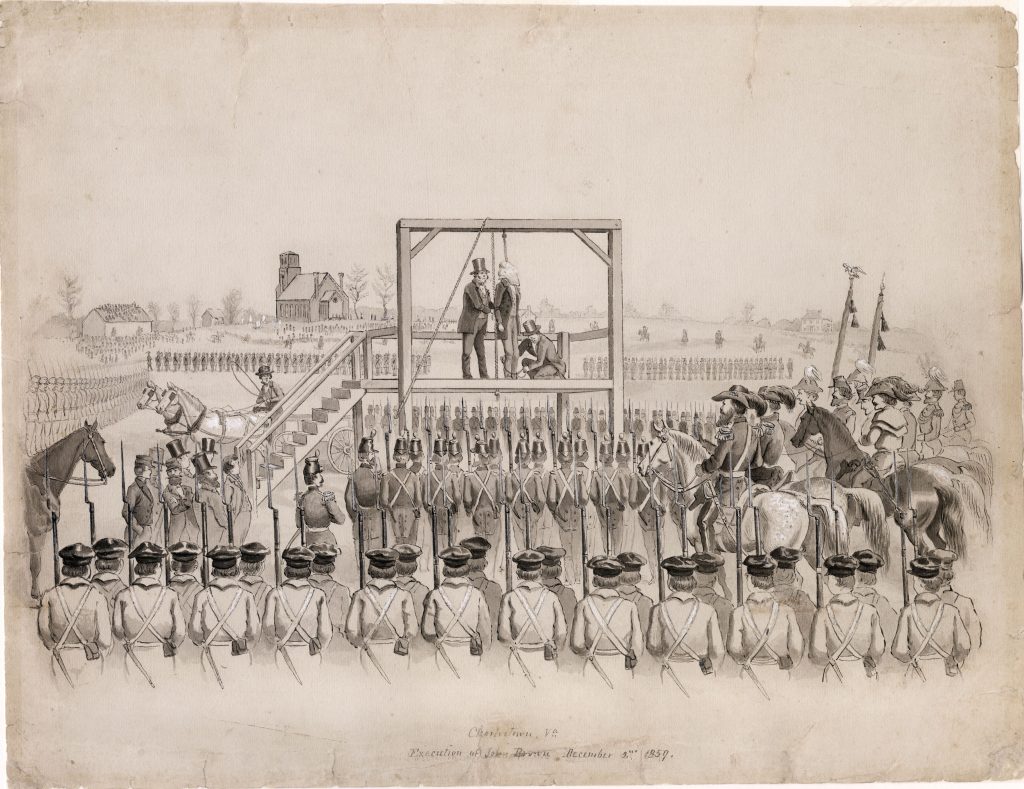

When John Brown’s body dropped through the gallows’ trap door in a field outside Charlestown, Virginia, at approximately 11 a.m. on December 2, 1859, only about 1,500 Virginia militia, Virginia Military Institute Cadets, and a handful of United States soldiers witnessed Brown’s last breath escape his body. Virginia Governor Henry Wise made it so. In fact, he wanted it that way. No civilians, just the military. (Wise was worried about rumored abolitionists who might try to free Brown at the last minute so he banned any civilians from attending the execution.)

Though most Americans did not see Brown’s final moments in person, they did not pass the time idly by. Bells echoed across the North at the hanging hour. Businesses closed. Churches held prayer services. Brown might have died in a field guarded by armed militia but more than 1,500 eyes were focused on the Charlestown gallows at the time of his execution. The North observed his death with solemnity while Southerners observed Brown’s hanging with one eye and kept the other watching the reactions of the North. Brown’s trial, not his raid, made him a martyr in the eyes of some Northerners, a sizable enough portion to make Southerners weary of Brown’s increasing popularity.

“I have always been a fervid Union man,” said one North Carolinian, “but I confess the endorsement of the Harper’s [sic] Ferry outrage…has shaken my fidelity and…I am willing to take the chances of every possible evil that may arise from disunion, sooner than submit any longer to Northern insolence.”

Frederick Douglass offered a different reaction: “When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone, the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union, and the clash of arms was at hand.”

Indeed, John Brown’s body may have been in the grave. But his soul was still very much alive after December 2, 1859.

Good post. Gov. Wise was no dummy and realized the disastrous effects that could have ensued for the slavery side had Brown’s followers been able to spring him and spirit him away. Had they gotten him to Canada, for example, he would have had a bully pulpit to continue his anti-slavery program. Wise wanted to make sure that Brown never uttered another word.

In a bit of irony, Wise advocated seizing the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, the same act for which he oversaw Brown’s execution. It was taken by Virginia Militia on April 18, 1861. After the war neither Wise, nor a single Confederate elected official or top military commander swung as punishment for their bloody four-year rebellion that killed hundreds of thousands.

Guess you get more attention when you’re the first guy to seize the Harpers Ferry arsenal.

No Confederate elected official, nor any officer were hung or tried because the courts would have found the federal government and northern states waged an unconstitutional war. There is one instance, the commandant of Andersonville was hung for supposed war crimes but nary a northern commandant was charged with war crimes at their POW camps.

Thanks for article. There were three historical figures that day that witness the execution of John Brown; Stonewall Jackson, John Wilkes Booth, and Walt Whitman. Stonewall as you would figure viewed it through a religious lens, feeling pity for a man whose life was about to go the ever after. Walt Whitman somewhat indifferent to the whole event did write about it in his poem Year of Meteors but his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, more inspired by the execution commented: “Now you have made the gallows as holy as the cross.” John Wilkes Brown a ardently pro-slavery supporter admired John Brown for his martyrdom and would do the exact the same thing he did but in reverse fours years later. Assassinate anti-slavery President Abraham Lincoln.

Brown was a complex man, a man who was convinced that slavery was a horrible wrong and the only way to destroy it was by insurrection. When that failed — and I do wonder if he really expected his attack on Harpers Ferry to work — he then decided to use his trial as a bully pulpit for attacking slavery.

He knew he would not be freed but he also seems to have realized that his death, properly orchestrated, would do more for the destruction of slavery than any other single thing he accomplished in his life.

He even forbid attempts by his friends to rescue him. He was intent on being a martyr. And Gov. Wise cooperated wonderfully. Wise should have locked Brown up as a lunatic — from Brown’s view, the worst possible end of the raid. But Wise couldn’t — even if he had wanted to. The fear of slave insurrection was so great in the Southern slaves that the slave states demanded Brown’s death.

Northern political leadership rejected Brown’s solution. In the early ’50s Lincoln had commented to the effect that, while slavery was a great wrong, it was better to accept it and live with it, than to create a greater wrong, decision. Salmon Chase commented “Poor old man! How sadly mislead by his own imagination.”

And in a speech, Lincoln was emphatic that Brown was not a Republican. However, Lincoln did say that Brown’s motives were noble, “he agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong,” but Lincoln condemned “violence, bloodshed, and treason.”

Brown, in his last weeks, aided by bloodthirsty Southerners, forged an image which helped unite the North when the secessionists fired on Sumter.

Emerson later compared Brown’s court room speech positively with the Gettysburg Address and wrote that Brown had made “the gallows glorious like the cross.” Henry Ward Beecher wrote “Let Virginia make him a martyr! Now, he has only blundered. His soul was noble, his work miserable. But a cord and a gibbet would redeem all that, and round up Brown’s failure with a heroic success.” Shown a copy of Beecher’s sermon, Brown scribbled “Good” above the passage about making him a martyr. Thoreau, a pacifist, Garrison, another pacifist, the list goes on and on, became convinced that only violence could destroy slavery. “It will be a terrible losing day for slavery when John Brown and his associates are brought to the gallows,” Garrison would write.

On the other side, the Mobile Register editorialized “The ark of covenant has been desecrated. For the first time the soil of the South has been invaded and its blood shed upon its own soil by armed abolitionist.” The new president of an Alabama college had to flee for his life because he was born in the North. A minister in Texas was publicly whipped because he had complained about the treatment of slaves. Around the slave states whites and blacks alike were lynched upon suspicion of being anti-slavery. Fire eaters like George Fitzhugh and J.D.B. De Bow were ecstatic at the confirmation of their preachings of the danger of the slave states failing to secede. As Alan Nevins would write, “The raid of twenty-two men on one Virginia town had sent a spasm of uneasiness, resentment and precautionary zeal from the Potomac to the Gulf.”

As he was led to the gallows, Brown handed his jailor his last words, “I John Brown am now quite _certain_ that the crimes of this _guilty_, _land_: _will_ never be purged _away_; but with Blood. I had _as I now think_: _vainly_ flattered myself that without _very much_ bloodshed: might be done.”

The issue about trying Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens and other political and military leaders of the Confederacy for treason was a complex one.

There were two reasons for not doing trying them: first was the feeling that a trial, if successful, would have created a martyr. In 1865, Jefferson Davis’ trial would probably have been applauded by most Confederates! But the exaggerated rumors of his mistreatment by Nelson Miles while Davis was held at Fortress Monroe changed the image of Davis among white Southerners from a hated incompetent to a martyr to the Lost Cause.

Carl Schurz, himself a fugitive from a failed rebellion in his native Germany, commented on the United States not executing the Rebels in a speech in the Senate: “There is not a single example of such magnanimity in the history of the world,” declared Schurz, “and it may be truly said that in acting as it did, this Republic was a century ahead of its time.”

Early Twentieth Century American historian James Ford Rhodes wrote, “With a just feeling of pride may we honour the officials and citizens, the Republicans and the Democrats, who contributed to this grand result. For assuredly it was a sublime thing that, despite the contentious partisanship of the time, men bitterly opposed on almost every other question, could agree that the highest wisdom demanded that Davis be released from prison and that he be not punished or even tried; that those in control recognized what had hitherto been so little appreciated ‘that the grass soon grows over blood shed upon the battle field, but never over blood shed upon the scaffold.’”

That said, there was another and equally potent issue. It had nothing to do with the number of Republicans on the Supreme Court or with long term thinking on the impact of executing ex-Confederates for treason. Instead it had to do with the United States Constitution’s very restrictive clause on what constitutes treason and, even more important, where and how charges of treason must be tried: Article III, Section 2 provides “The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed,” and Section 3 states “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court. The Congress shall have Power to declare the Punishment of Treason.”

The Constitutional Convention had deliberately made it difficult to convict someone of treason, because of fears of abuse. In addition, Chief Justice John Marshall, sitting as a district court judge in Richmond (much like his successor, Taney, had done in ex parte Merryman) in the Aaron Burr trial had set even higher standards, in Marshall’s case to embarrass his political enemy, Thomas Jefferson.

There have only been a handful of treason trials in American history: several men involved in the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s were convicted but later pardoned. In ex parte Bollman, 8 US (4 Cr) 75 (1807), one of the Burr conspirators was freed because the indictment was in the District of Columbia and Bollman had never been there. Chief Justice Marshall ruled that the indictment and trial would have to be held where the alleged treason had actually occurred, not, to carry the argument to the Civil War, in Pennsylvania, because, even though the Army of Northern Virginia paid a visit, President Davis was never there. The Burr Trial, United States v. Burr, 8 US (4 Cr.) 469, Appx. (1807) ruled that Burr could not be convicted unless two witnesses testified to Burr’s actual involvement. Since that was a secret conspiracy, there was no one to testify against Burr.

After 1807 it was World War II before there was another Treason Trial! Of the three post-1945 trials, only two were upheld: in the United States treason is an extremely difficult crime to prosecute.

In 1865, facing this issue, the Andrew Johnson Administration wanted the best legal counsel possible if it was to try any of the Confederate leadership. The Administration appointed a Special Prosecutor, a man most of us know for a very different reason: Richard Henry Dana, Jr. We read back in junior high his classic sea story, Two Years Before the Mast. What we forget is that Dana wrote the book, not as an adventure story for boys, but as an expose on the conditions faced by the common seamen of the 1840s. After completing law school, Dana became a leading attorney defending the less fortunate, whether they were seamen abused by their captains or employers or accused escaped slaves.

In 1861, President Lincoln appointed Dana as United States Attorney for the District of Massachusetts. As such, in 1863, he successfully defended the United States in the Prize Cases before the United States Supreme Court. These were a group of cases, consolidated on appeal, on the capture of ships attempting to break the blockade of the Confederate ports. The issue argued revolved around two separate issues: was the Rebellion a “war” and when did the “Civil War” begin, in April 1861, with President Lincoln’s Declaration of a blockade or in the summer when Congress approved what the president had done. The court unanimously ruled in favor of the administration’s position that the Rebellion was a war but more narrowly (5-4) supported the premise that the president’s call for troops on April marked the beginning of the war. Not surprisingly Chief Justice Taney felt that the war could only begin when Congress said it did, very much as he had done in ex parte Merryman [67 U.S. (2 Black) 635, on line at http://www2.law.cornell.edu ]

The first question in any post-war treason trial was, had Davis waged war against the United States? Obviously. Second, where had he waged war? Probably in Virginia. Perhaps in Montgomery.

Well, then, he would have to be tried in Virginia, in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. This was the court which, sitting in Richmond, had indicted not only Davis, but also a number of prominent Confederates, including Robert E. Lee. Now the rub: according to Article II, Section 2, Davis, and anyone else, would have to be tried in Virginia, before a jury of Virginians! Remember that no blacks would qualify for a jury in 1865 or 1866, indeed, if would have been hard to empanel a jury, which did not contain either ex-Confederates or Confederate sympathizers. And Dana was very concerned about the ability of the Government to convince twelve Virginians that Davis had committed a crime.

Let Dana, in a letter to Attorney General W.M. Evarts on August 24, 1868, expressed his opinion why there should be no attempt to try Davis (and by extension, any other Confederate) for their activities during the War. The letter is a little long but I think it important to read all of it.

“Sir,

“While preparing with yourself, before you assumed your present post, to perform the honorable duty the President had assigned to us, of conducting the trial of Jefferson Davis, you know how much my mind was moved, from the first, by doubts of the expediency of trying him at all. The reasons which prevented my presenting those doubts no longer exist, and they have so ripened into conviction that I feel it my duty to lay them before you in form, as you now hold a post of official responsibly for the proceeding.

“After the most serious reflection, I cannot see any good reason why the Government should make a question whether the late civil war was treason, and whether Jefferson Davis took any part in it, and submit those questions to the decision of a petit jury of the vicinage of Richmond at nisi prius.

“As the Constitution in terms settles the fact that our republic is a state against which treason may be committed, the only constitutional question attending the late war was whether a levying of war against the United States which would otherwise be treason, is relieved of that character by the fact that it took the form of secession from the Union by state authority. In other words the legal issue was, whether secession by a State is a right, making an act legal and obligatory upon the nation which would otherwise have been treason.

“This issue I suppose to have been settled by the action of every department of the Government, by the action of the people itself, and by those events which are definitive in the affairs of men.

“The Supreme Court in the Prize Causes held, by happily a unanimous opinion, that acts of the States, whether secession ordinances, or in whatever form cast, could not be brought into the cases, as justifications for the war, and had no legal effect on the character of the war, or on the political status of territory or persons or property, and that the line of enemy’s territory was a question of fact, depending upon the line of bayonets of an actual war. The rule in the Prize Causes has been steadily followed in the Supreme Court since, and in the Circuit Courts, without an intimation of a doubt. That the law making and executive departments have treated this secession and war as treason, is matter of history, as well as is the action of the people in the highest sanction of war.

“It cannot be doubted that the Circuit Court at the trial will instruct the jury, in conformity with these decisions, that the late attempt to establish and sustain by war an independent empire within the United States was treason. The only question of fact submitted to the Jury will be whether Jefferson Davis took any part in the war. As it is one of the great facts of history that he was its head, civil and military, why should we desire to make a question of it and refer its decision to a jury, with power to find in the negative or affirmative, or to disagree? It is not an appropriate question for the decision of a jury; certainly it is not a fact which a Government should, without great cause, give a jury a chance to ignore.

“We know that these indictments are to be tried in what was for five years enemy’s territory, which is not yet restored to the exercise of all its political functions, and where the fires are not extinct. We know that it only requires one dissentient juror to defeat the Government and give Jefferson Davis and his favorers a triumph. Now, is not such a result one which we must include in our calculation of possibilities? Whatever modes may be legally adopted to draw a jury, or to purge it, and whatever the influence of the court or of counsel, we know that a favorer of treason may get upon the jury. But that is not necessary. A fear of personal violence or social ostracism may be enough to induce one man to withhold his assent from the verdict, especially as be need not come forward personally, nor give a reason, even in the jury-room.

“This possible result would be most humiliating to the Government and people of this country, and none the less so from the fact that it would be absurd. The Government would be stopped in its judicial course because it could neither assume nor judicially determine that Jefferson Davis took part in the late civil war. Such a result would also bring into doubt the adequacy of our penal system to deal with such cases as this.

“If it were important to secure a verdict as a means of punishing the defendant, the question would present itself differently. But it would be beneath the dignity of the Government and of the issue, to inflict upon him a minor punishment; and, as to a sentence of death, I am sure that, after this lapse of time and after all that has occurred in the interval, the people of the United States would not desire to see it enforced.

“In fine, after the fullest consideration, it seems to me that, by pursuing the trial, the Government can get only a re-affirmation by a Circuit Court at nisi prius of a rule of public law settled for this country in every way in which such a matter can be settled, only giving to a jury drawn from the region of the rebellion a chance to disregard the law when announced. It gives that jury a like opportunity to ignore the fact that Jefferson Davis took any part in the late civil war. And one man upon the jury can secure these results. The risks of such absurd and discreditable issues of a great state trial are assumed for the sake of a verdict which, if obtained, will settle nothing in law or national practice not now settled, and nothing in fact not now history, while no judgment rendered thereon do we think will be ever executed.

“Besides these reasons, and perhaps because of them, I think that the public interest in the trial has ceased among the most earnest and loyal citizens.

“If your views and those of the President should be in favor of proceeding with the trial, I am confident that I can do my duty as counsel, to the utmost of my ability and with all zeal. For my doubts are not what the verdict ought to be. On the contrary, I should feel all the more strongly, if the trial is begun, the importance of a victory to the Government, and the necessity of putting forth all powers and using all lawful means to secure it. Still, I feel it my duty to say that if the President should judge otherwise, my position in the cause is at his disposal.”

President Johnson noted on the letter, “This opinion must be filed with care, A.J.”

On the following Christmas, President Johnson issued an amnesty proclamation which included Davis, and, as a result, in February 1869 an order of nolle prosequi was entered, and Davis and his bondsmen were released.

Thanks, Bob for those two excellent posts. The legal practicalities as conditioned by the language of the Constitution do seem to make the point that such a trial would be virtually unwinnable given a jury of white male Virginians in 1868. This is a case of “straining at a gnat but swallowing a camel.” That Davis was clearly guilty of treason is plainly obvious. In lieu of a Constitutional amendment to reframe the method of prosecution, however, it appears that directing armies that fire on the US flag is not treasonable enough.

“That Davis was clearly guilty of treason is plainly obvious”

Is it now? The finest legal minds of the day seemed unwilling to bring themselves to rule on the matter for fear of bringing into question the wholesale slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Americans for the purpose of subjugating millions more under martial law.

“What a beautiful country”… would be great if he said such right before he was hanged.

I enjoyed the Good Lord Bird — thoughtful, while still be entertaining. Well done to all the folks involved with it,