Treüe der Union: A German Union Man Cheats Death in Texas

Three days after the attack on August 10, 1862, Ernst Cramer returned to the battlefield near the Nueces River to search for his wounded friends. Nineteen dead German Americans, bloated, blackened, and putrid in the unrelenting west Texas heat lay naked in a heap near the freshly-dug graves of Confederate soldiers. Entering a nearby cedar brake, Cramer recoiled at another gruesome sight. Nine wounded comrades had been dragged into a line and executed with a shot to the forehead, their bodies subsequently riddled with dozens of bullets. Cramer and a handful of survivors crept away from the macabre scene knowing that their ordeal as fugitives from the Confederacy had only just begun.

Cramer and his fellow Unionists were among nearly twenty thousand Germans who settled in the Hill Country in south-central Texas during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Many German Americans in this region were anti-slavery, freethinkers, and recent political refugees from the failed democratic republican uprisings of 1848. Nearly all Hill Country counties were strongly pro-Union. In the June 23, 1861 secession election, seventy-six percent of Texans voted for disunion, despite the fact that just two years earlier, stalwart Unionist Sam Houston had been elected governor, defeating a secessionist incumbent. German-dominated counties, in contrast, voted overwhelmingly against secession. German Union men became fierce and active opponents of the Confederate government, vowing to never betray the United States.

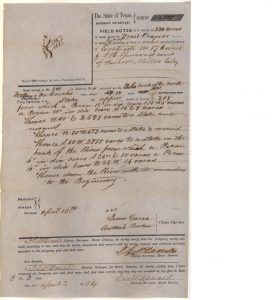

In March 1862, eighteen Union Loyal League militias organized, ostensibly to protect their communities against threats from hostile Native American tribes and desperados. Up to this time, Confederate authorities had not suspected Cramer of sedition, since he was a county tax collector. He promptly resigned and joined the insurgents. Germans raised the Union flag at a spring near Fredericksburg on March 24 and elected Cramer captain of the 80-man Comfort District company.

Tensions accelerated when the Confederate government implemented conscription in April. Colonel Henry Eustace McCullough, commander of the Western Sub-District of Texas, organized a force to crush the German militias and declared martial law. Local residents were forced to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy or lose their property. Most militiamen took the oath, leaving Cramer and other officers few alternatives but to flee into the mountains. In Gillespie County, two Union men were executed by Confederate soldiers. The Loyal League responded by ambushing and killing Basil Stewart, a former member turned informant. As the violence spread and the call came to conscript all men under the age of 35, more Unionists left their families and went into hiding.

Cramer and approximately twenty other refugees felt threatened by the presence of more than 600 Confederate troops, so they started for Mexico on August 2, intending to join Union forces at the first opportunity. Near the source of the Guadalupe River, they rendezvoused with forty more Germans and five others and continued for a week through the mountains toward Del Rio, Texas where they could cross the Rio Grande River. They reached a meadow on an outer arm of the Nueces River with ample grass and water for their horses and made camp about forty-five miles from their destination. It was a beautiful spot, partly surrounded by cedars. The men talked cheerfully and sang well into the night, having no inkling that many of them were about to take their final breaths.

A single shot shattered the moonlit silence, dropping one of two guards and waking everyone. As they leaped to their feet, a hundred volleys pierced the campsite, wounding four Germans and killing Cramer’s brother-in-law. Unbeknownst to the Unionists, a force composed of ninety-six men from Duff’s Partisan Rangers, the Second Texas Mounted Rifles, and the Eighth Texas Cavalry under the command of First Lt. Colin McRae had been tracking them for days. Ninety Confederates split into two groups. McRae approached from the southwest and Lt. James Horsley stole in from the northeast. They were only fifty yards away when they opened fire on the sleeping Germans. Horsley’s men charged, but were beaten back. McRae’s troops maintained their position. An eerie silence then ensued for several hours as the Germans erected crude breastworks. By daybreak, twenty-three men who had joined Cramer at Guadalupe Spring had left their posts, leaving just thirty-two unwounded Unionists facing off against a force nearly three times their size.

At daybreak, the battle resumed. Horsley and McRae’s troops charged the camp several times with heavy casualties on both sides. Germans killed two Confederates and wounded nineteen others, including McRae twice. After a few hours, only Cramer and three of his comrades remained uninjured. They opted to withdraw to a thick growth of cedars across the water from the meadow with a small group of men who were not seriously wounded. Traveling up a valley, they encountered eight others who had deserted them during the fight and reluctantly agreed to rejoin them. Later that afternoon, they returned to the river to fill their powder horns with water and attempt to reach the wounded, but enemy soldiers were a mere 150 steps away. They waited several days for the soldiers to withdraw, only to discover a ghastly scene where many dead friends lay rotting in the sun, including nine wounded men murdered on the order of Lt. Edwin Lilly of the Partisan Rangers.

Cramer and several desperately hungry companions walked more than ninety miles in four days back to Comfort to gather provisions. Secreted in a thicket just a half mile from his home, Cramer could not risk seeing his wife to tell her that one of her brothers was dead and another missing and presumed dead. The following day, he walked eighteen miles to Boerne, where he begged a friend to break the news to his family. For four days, Cramer laid in his friend’s house, delirious with fever. He heard exaggerated claims that more than a hundred Texas Germans had been hanged in the past three months. He secured a horse from a former comrade and set out again for Mexico. Cramer and thirteen others made it to the Rio Grande this time, intending to cross a few at a time in various locations to evade Confederates. Most of them never made it.

Cramer’s friends Moritz and Franz Weiss came under heavy fire, abandoned their horses and ammunition, and attempted to swim the river. Franz was wounded and when Moritz tried to save him, both men drowned. In all, eight Germans died at the river on October 18, 1862. Only Cramer and a friend crossed safely. They rode another 301 miles to Monterey, Mexico where Cramer recounted his trials in a long letter to his parents on October 30. It was far too dangerous to return home. The Hill Country erupted in guerilla warfare. Confederate sympathizers hunted and hanged Union men, loyalists murdered Confederate officials, and gangs of outlaws terrorized defenseless families on both sides. By March 1864, Cramer still had not returned, so his wife and extended family moved to relative safety in San Antonio.

After the war ended, Ernst Cramer moved his family to the Mexican border town of Piedras Negras, where he worked as a miller for a few years. His loyalty to the Union was rewarded in 1868, when he was awarded the plumb post of U.S. customs collector in Eagle Pass, Texas, a job that paid $1500 annually and allowed him to rebuild his lost fortune. He then moved back to Comfort for a few years and later ventured to Santa Clara, California and Hailey, Idaho, where he died a successful businessman in 1916.

Survivors who had been afraid to visit the site of the battle near the Nueces River during the war, finally returned in 1865 to collect the scattered bones of friends and family members. They carted the remains back to Comfort and interred them in a bucolic setting surrounded by live oaks. Local residents and families of the victims funded and erected a twenty-foot-high limestone obelisk with four panels bearing the names of Cramer’s thirty-six comrades who had died on the battlefield and at the Rio Grande along with thirty-two others who gave their lives supporting the Union. Comfort residents dedicated the monument on August 10, 1866, precisely four years to the day following the bloodshed alongside the Nueces. A thirty-six-star US flag at half-mast has flown there ever since.

More than 200,000 German Americans fought for the US during the Civil War. Their stories and those of other recent immigrants remain underrepresented in historical literature, despite their critical contributions the Federal army. German Unionists on the Texas home front and thousands of loyal U.S. citizens across the Confederacy also deserve further study, so scholars may consign myths like the “solid South” and the Lost Cause to their eternal and proper resting place in the dustbin of false history.

David T. Dixon’s latest book is Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General, published by University of Tennessee Press (2020).

Sources:

Kamphoefner, Walter D. and Helbich, Wolfgang, eds. Germans in the Civil War: The Letters They Wrote Home. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Kamphoefner, Walter D. “New Americans of New Southerners? Unionist German Texans.” In Lone Star Unionism, Dissent, and Resistance, edited by Jesus F. de la Teja, 101—122. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 2016.

Roland, Nicholas K. “‘Our Worst Enemies Are in Our Midst’: Violence in the Texas Hill Country, 1845-1881.” Ph. D. diss., Univ. of Texas, 2017.

Nice post. Thanks. As I understand it, there were also some 300 Germans from Comal County, one of those Hill Country counties, who fought for the Confederacy. That was a complicated time.

Tom Crane

Thanks for your reply, Tom. Comal County was definitely an outlier as Germans in the balance of the hill Country counties voted overwhelmingly against secession. Gillespie Co voted 96% against secession and Mason County 97% against. Walter Kamphoefner, the leading scholar of German Americans in Texas, suggests that support for the Confederacy among Germans in New Braunfels and the balance of Comal County has been misunderstood. The local newspaper editor warned his fellow Germans of reprisals unless they “do as Texans do…anything else is suicide.” Kamphoefner concludes that intimidation was a key factor in this aberration among German residents of the Hill Country.

As for the 300 Germans from Comal County who “fought” for the Confederacy, what is the source for that information? How many of them were volunteers and how many conscripted? Of these, how many deserted or saw combat service? It would be interesting to follow that paper trail and assess how many German Texans enlisted willingly and served enthusiastically.

I see that the Texas State Historical website claims 260 Comal County residents served in the Confederates army in three companies. At least two of those companies were led by German American captains. Fascinating that one community in the Hill Country bucked the trend of German American support for the Union. Thanks for pointing that out.

Sorry the author feels the need to victimize the Unionist community in a civil war. His narrative is marred by his partisanship. He frequently praises the German community for being “staunchly” Unionist and refusing to “betray” the Union. To most of their fellow citizens, they were merely viewed as a Fifth Column, disloyal both to Texas and the Confederacy. The Unionist German community in Saint Louis had already been prominent is assisting Lyons and Blair in overthrowing what many Missourians viewed as the legitimate state government, though they viewed it’s activities as disloyal. The Texans were hardly unaware of this. As unsavory as the actions were, they were consistent with those on the borderlands of a civil war. They were no different than those of Bloody Bill Anderson or Senator Lane.

Thanks for your comment, John. Loyalty in times of Civil War can be an ambiguous concept. I am sure those Texas Confederates who certainly betrayed the United States government, illegally (according to Robert E. Lee) executed a military coup against U.S. Army forces in San Antonio (before secession was ratified by popular vote), and defied the authority of their own governor felt that German American Unionists were betraying their adopted home state. Both Texas Confederates and German Unionists were guilty of violence during this period.

I think your argument might be stronger if one considers that many Unionists had an opportunity to leave Texas when the Confederate government passed the Alien Enemy Act on August 8, 1861. Because Texas was on the frontier, Union men and their families were given until the end of October to leave the state, and thousands did so. Most German Texans like Cramer stayed, however, as abandoning their property meant financial ruin. If their calculation was to lay low and ride out the war as noncombatants, those options evaporated in 1862, and particularly with conscription. At that point they had to defend themselves against threats from increasingly hostile Confederate sympathizers who resented them.

I don’t believe I paint all Texas German Unionists as victims, though I think we can all agree that the well-documented execution of the wounded Germans at the Nueces is beyond the pale by any standard, as was the summary execution of an informant by The Loyal League.