When President Kennedy–and Professor Wiley–Stepped In

In the final report of the U.S. Civil War Centennial Commission, issued in 1968, Chairman Allan Nevins recalled “the great wave of popular interest in the Civil War” that led Congress to authorize the Commission in 1957. He also remembered that the group faced “the disadvantage of doing its work while a new crisis in the long history of racial irritations in America gripped parts of the nation.”

In the final report of the U.S. Civil War Centennial Commission, issued in 1968, Chairman Allan Nevins recalled “the great wave of popular interest in the Civil War” that led Congress to authorize the Commission in 1957. He also remembered that the group faced “the disadvantage of doing its work while a new crisis in the long history of racial irritations in America gripped parts of the nation.”

Those racial irritations were manifest as the CWCC prepared to hold its Fourth National Assembly, or annual convention, in Charleston. The event was scheduled for April 11-12, 1961, when the South Carolina Commission on the War Between the States planned a spectacular reenactment of the bombardment of Fort Sumter. That was appealing to the CWCC leadership, but not to all Commission members. The event had been booked in a hotel, the Francis Marion, that practiced a policy of segregation.

The Civil Rights movement was already afoot; recall that the first sit-in had occurred at Woolworth’s in Greensboro in February 1960. A year later, on Feb. 4, 1961, Everett Landers, executive director of the New Jersey Civil War Centennial Commission, wrote Karl Betts, the national Commission chairman: “As you may know, one of our members, Mrs. Williams, is a Negro. She has expressed concern over her reception by hotel people in South Carolina.” The sixty-five year-old Madeline A. Williams knew what she was talking about; her husband was president of the local branch of the NAACP. She herself was the Essex County registrar and a former New Jersey assembly member.

A few days later Chairman Betts wrote Charleston’s Chamber of Commerce, asking what kind of reception a Northern black woman might expect at the Francis Marion. Otherwise, Betts did nothing, which irritated the New Jerseyans; they started talking about boycotting the convention in protest. The New York Times and other papers picked up the story, which suggested that Civil Rights activists saw the upcoming CWCC meeting as something of a test. Politicians began weighing in; the New Jersey legislature called for a change of venue for the Commission convention.

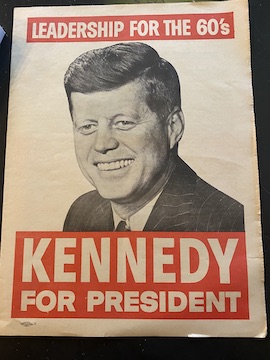

In early March all this got the attention of President Kennedy, who, just a few months in office, had begun to stake out his administration’s Civil Rights agenda. A White House staffer began researching what authority the president had in the matter. (After all, the Commission was receiving federal funding.)

In early March all this got the attention of President Kennedy, who, just a few months in office, had begun to stake out his administration’s Civil Rights agenda. A White House staffer began researching what authority the president had in the matter. (After all, the Commission was receiving federal funding.)

The idea was already floating of offering a desegregated federal military installation as the CWCC assembly site. Then Kennedy acted. In a letter of March 14 to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant III, the Commission chairman, the president declared his belief that “the Commission has the responsibility to see that all of its members and guests are treated on a basis of equality at all the facilities arranged by the Commission.”

At this point Emory professor Bell Wiley, a Commission member, asked General Grant for permission to call the Francis Marion Hotel manager, who told him that with so much publicity stirred up, the hotel would not be able to accommodate Mrs. Williams. Dr. Wiley then proposed what the White House had been thinking—move the meeting from the segregated downtown hotel to a federal base outside of the city.

Tensions ran higher when the White House gave the Kennedy-Grant letter to the press. When the CWCC executive committee met on March 21, it voted to take no action on behalf of Madeline Williams or the New Jersey delegation. Vice Chairman Bill Tuck was given the job of conveying the Commission’s position in a letter to President Kennedy. Tuck had no problem with this; the Virginia congressman was a diehard segregationist who had already expressed opposition to federal interference in Southern affairs.

When the press publicized Tuck’s views, the results were predictable. The New Jersey CWCC formally condemned the national Commission. The state centennial commissions of New York, Illinois and California voted to join New Jersey in boycotting the upcoming assembly. Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP, echoed his dismay at the CWCC’s apparent buy-in “to the racial theories which brought on the Civil War.” On the other side, diehard Southerners warned of Communist agents within the New Jersey commission. When Kennedy announced that his administration would not allow a federally-funded arm to aid Jim Crow—“President Tells Civil War Unit Not to Hold Segregated Meeting” was the New York Times’ front-page headline–South Carolina governor Fritz Hollings and Sen. Strom Thurmond challenged the executive branch’s authority to force the Commission, which had been established by Congress, to do anything.

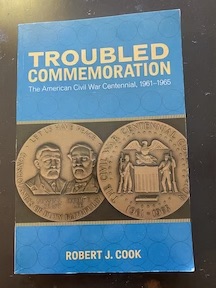

Academics like Wiley and other historians tried to work out a solution. Bruce Catton, chair  of the New York Centennial Commission, warned Grant that Tuck’s letter made it appear that the CWCC was endorsing racial discrimination. Wiley kept pursuing the compromise: keeping the national convention at Charleston, just in the naval station outside. The idea had political implications, too. As Robert J. Cook has written in Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial, 1961-1965 (2007), “transferring the assembly to an integrated military base signaled federal distaste for Jim Crow, but the move had no concrete impact on the existence of segregation laws in the southern states.” (That was where we were in 1961.)

of the New York Centennial Commission, warned Grant that Tuck’s letter made it appear that the CWCC was endorsing racial discrimination. Wiley kept pursuing the compromise: keeping the national convention at Charleston, just in the naval station outside. The idea had political implications, too. As Robert J. Cook has written in Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial, 1961-1965 (2007), “transferring the assembly to an integrated military base signaled federal distaste for Jim Crow, but the move had no concrete impact on the existence of segregation laws in the southern states.” (That was where we were in 1961.)

Awash in nationwide bad publicity, with the entire Centennial at risk of imploding, Grant and the Commission caved. On March 25, the chairman announced that the CWCC assembly would be held at the naval station, “in compliance with the President’s policy.” Madeline Williams understandably exulted over this “victory for the democratic process in America.”

Dr. Wiley was especially overjoyed. The accommodation meant, as he put it, that “we can go ahead and commemorate the war as Americans.” “I was afraid that if the National Assembly was called off altogether, or taken away from Charleston,” he added, “Southern states might pull out of the commemorative program—that would be the end, in my opinion.”

In 1968 I was a junior at Emory. I had already developed a high regard for Dr. Wiley before I took his Civil War course, for a host of reasons. Had I known all of this then, I would have added to them this one: saving the 1961 National Assembly of the Civil War Centennial Commission—and perhaps saving the Centennial itself.

N.B. “The ensuing convention proceeded with its work,” the 1968 Commission report declared, “amid only a few expressions of ill will on either side.”

But repercussions continued. The Commission’s Executive Director, Karl S. Betts, resigned “under pressure from the Charleston blunder.” The Vice Chairman, William M. Tuck, also left—he was a Congressman and cited work demands. Vice Admiral Stuart H. Ingersoll, another Commission member, resigned a few weeks later.

Thank you for this article.

Sad that after Jackie Robinson broke the color-barrier with his ability in 1947, that Afro-Americans were still treated as 2nd class citizens.

And after they had served their country in WW 2.

I had recently learned about this and wanted to know more details. Thank you for sharing!