A.C.L. Gatewood, the Lost Cause, and Two Different Accounts of the Appomattox Campaign

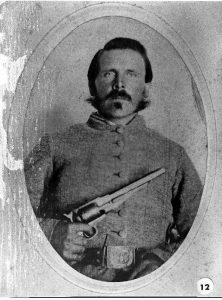

Andrew Cameron Lewis Gatewood came from an influential family in Bath County, Virginia. Before the war, the wealth and status of his family helped secure him a position as a cadet at the Virginia Military Institute. He spent most of the war in the Bath Squadron, initially Co. F of the 17th Virginia Cavalry Battalion and later Co. F of the 11th Virginia Cavalry. He saw much combat throughout the war and was eventually commissioned a Second Lieutenant. Postwar, the ideology of the Lost Cause took a strong hold in former Confederate soldiers, and Gatewood was no exception. Designed to explain the defeat while keeping the honor and glory of Confederate soldiers intact, the ideology rewrote the way people thought of and remembered the war. Gatewood’s two accounts of the Appomattox Campaign, period diary entries preserved in the West Virginia and Regional History Center and postwar compilations in the “History of the Bath Squadron or Recollections of Thirty Years Ago,” are two very different animals. One is brutally honest, while the other sees the past through rose-tinted glasses.

As the siege of Petersburg ground to an end the 11th Virginia Cavalry was near the city, held in reserve during the disastrous Battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865. Gatewood wrote that this battle was “the beginning of the end.”[1] Soon after, the Army of Northern Virginia began to withdraw from Petersburg and the cavalry moved towards Amelia Court House, skirmishing with Union troops along the way.[2] Gatewood later described this retreat in a fashion perfectly aligned with the Lost Cause view of the ideal Confederate soldier:

the troops, then suffering for food and sleep, marched over roads made heavy from copious rains, were buoyant in spirit, brave in heart, and of undoubted morale…They were soldiers of no ordinary mold, who had an abiding faith amounting to fanaticism that the God of battles would in the end send their cause safe deliverance, and they followed Lee with an almost childlike faith….The morale of this remnant of the great Army of Northern Virginia was untouched.[3]

The Appomattox Campaign had begun, and the Confederate Army was already suffering from lack of food for men and forage for horses. Despite Gatewood’s assurances long after the war, the morale of the army was disintegrating, and many soldiers collapsed or deserted. Dejected as the army retreated, Gatewood penned a note in 1865 that showed how little soldiers understood of the overall situation, writing “It is reported that Richmond, the capital of the Confederate States was evacuated the night of the 2nd of April. Suppose if true the enemy took it on the 3rd.”[4] On the 5th, the 11th Virginia Cavalry was engaged near Amelia Springs, Virginia, in hopes of defending a wagon train of supplies. Following a sabre charge, the Union forces were driven back, but the regiment was accumulating casualties, and the army had found no supplies waiting for them at Amelia Court House.[5] That night Gatewood described his situation: “the enemy broke into our wagon train…I had my horse’s thigh broken.”[6] Dismounted, he gathered his saddle and baggage, and searched for a horse in case his men were driven off. A horse came up to him, still bearing its rider, dead in the saddle, and Gatewood acquired a new mount.[7] Gatewood later acknowledged the poor condition of the army, writing, “there is only one other [retreat] that equals it – Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow,” but continued to paint it with Lost Cause heroism by stating, “the old guard of the army of Northern Virginia still stood to their colors, fighting every step, despairing but not shirking, and obeying the orders of Lee to the Last.”[8]

Gatewood admitted that due to the rigors of the campaign “the men and horses were both well nigh broken down from fatigue and loss of sleep.”[9] That night, they encamped near Appomattox Court House, and prepared to attack Union forces the next day. Near sunrise on April 9th, the 11th Virginia Cavalry and the Laurel Brigade made their final assault. Though it initially had some success, more Union troops were arriving, and soon flags of truce began to appear. The Army of Northern Virginia was prepared to surrender, and the 11th lost two men killed in their final battle.[10]

Gatewood wrote little of this in his post-war reminisces, simply reinforcing Lost Cause narratives of honor and sacrifice by stating, “the splendid army with whose courage and heroism a world was familiar, was reduced to a fragment of brave men, many of whom from exposure and want of food, could not lift a musket to the shoulder.”[11] Though his letters and diary entries throughout the war had mentioned acts of bravery, they often emphasized stress and suffering. Now, with the distance of several decades Gatewood dramatized the heroism and rewrote his narrative into the mold popularized by the Lost Cause. Despite Gatewood’s assertions of the bravery and heroism of the army decades after the war had ended, Lee himself had bitterly disagreed during the war. In April 1865, Lee had written to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that as the army left Petersburg it began to disintegrate, and that his men were demoralized, lacking their prior courage, and deserted en masse.[12] This is a far cry from Gatewood’s claim that they were “buoyant in spirit, brave in heart, and of undoubted morale.”

Gatewood didn’t surrender at Appomattox in April 1865. He, along with other Confederate cavalry, fled to Lynchburg in hopes of continuing the fight. Despite his later pride in his parole pass, he may have been embarrassed to surrender and not recorded the event. Nevertheless, Gatewood and the others eventually found it necessary to submit themselves to Union authorities and receive their parole. In any case, by July his diary turned away from war and politics and towards recording farm business. Gatewood’s war was over. Afterward, he received a degree from VMI since he left before graduating, married, served in the Virginia Militia, moved to family property in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, and played an active role in the West Virginia Division of the United Confederate Veterans. Later, he penned his memoir of service for the local paper, an account that drastically differs from the tone and mood of many of his earlier writings. Memory is a fickle thing, but Gatewood’s later account twisted his writings from 1865 into something that better fit the mold of the Lost Cause. When he died at the age of 76, one obituary said, “as a soldier he measured up to the highest standard and as a man and citizen he held the confidence and high regard of all,” and concluded with a deeply Lost Cause statement, “May he rest in peace with Lee and Jackson under the shade of the trees,” referencing the final words of Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson.[13]

[1] History of the Bath Squadron, Andrew C.L. Gatewood Papers, VMI Archives, 75.

[2] Richard L. Armstrong, 11th Virginia Cavalry (Lynchburg, Va.: H.E. Howard, 1989), 98.

[3] History of the Bath Squadron, Andrew C.L. Gatewood Papers, VMI Archives, 77.

[4] Diary April 3rd, 1865, A.C.L. Gatewood Papers, WVRHC.

[5] Thomas L. Rosser, Riding with Rosser, edited by S. Roger Keller (Shippensburg: White Mane Publishing, 1997), 67.

[6] Diary April 5th, 1865, A.C.L. Gatewood Papers, WVRHC.

[7] History of the Bath Squadron, Andrew C.L. Gatewood Papers, VMI Archives, 81.

[8] Ibid, 78.

[9] Ibid, 80.

[10] Armstrong, 100-101.

[11] History of the Bath Squadron, Andrew C.L. Gatewood Papers, VMI Archives, 81.

[12] Elizabeth R. Varon, Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War (Oxford:Oxford University Press, 2014), 76.

[13] “General Gatewood Dead,” Harlan Genealogy, http://www.harlangenealogy.org/death/Obituary%20of%20A%20C%20L%20Gatewood.pdf

It is both simplistic and self serving to ascribe the differences in accounts to a Lost Cause template. A comparison of accounts written immediately after battles and years later by participants of both armies reveals similar distortions of memory. Most are simply self defensive mechanisms to give meaning to the horrors endured. There is a similar tone in both Union and Confederate narratives in describing both defeats and victories, in sacrifice and triumphalism.

Hi John,

I certainly agree with you that the intricacies and distortions of memory are common between both Union and Confederate veterans – I’ve written on both. However, I do also believe that those distortions common to time can indeed coexist and work with Lost Cause distortions. As I have examined his numerous period letters from across the war and his late-war diary in comparison to his post-war newspaper column and community involvement, I stand by my conclusion.

I think we should make a distinction between Lost Cause historiography and the personal remembrances of a soldier. The former is condemnable as the more or less conscious and deliberate misrepresentations of events, causes, and intentions by public figures for personal or political gain. The Lost Cause has become the object of rebuke and derision, with justification. The latter can be understood as the struggles of a brave, dedicated man over the years to cope with tragedy while retaining some dignity. His vagaries of memory are instructive for different reasons; they deserve understanding and respect.

As in my response to John, I agree that there is a distinction between the two, but see this as indeed tied to the Lost Cause. Gatewood’s later writing attributes a great deal more glory to the Appomattox Campaign, which I see as connected to the Lost Cause’s image of the ideal Confederate soldier who was only slowly outmatched by the United States’ materials and manpower. It seeks to justify the defeat without dishonor.

Your right, Jon. Many in the North and South adopted Lost Cause mythology as comforting and reassuring. Many still do. It resolves cognitive dissonance and buries uncomfortable truths, which demonstrates both the tragedy of the war and the human capacity for self delusion. And there are lots of similarly false social mythologies in play today. That’s why we study history: to see ourselves in the lives of our ancestors.

Jon, the trouble with your argument is that a good, non Lost Cause analysis can be made that at least as far as the combat in the East goes, numbers really, really, really made a difference. Grant’s strategic excellence was more than compensated by a tactical nonchalance that squandered, through haste and poor reconnaissance, many of the lives of his men.