A Comprehensive View of the Overland Campaign: Part I

Emerging Civil War welcomes back Nathan Provost…

Antoine-Henri Jomini was a general in the Napoleonic Wars who served under various generals, including Napoleon himself. After Napoleon Bonaparte’s exile, Jomini began writing a series of works that dealt with the principles of war. He claimed that great captains possessed the coup d’oeil, or comprehensive view. They could quickly analyze a battlefield or map and determine the next action.[1] Carl von Clausewitz includes the coup d’oeil as one of the many traits needed for a military genius. By the end of winter 1864, General Robert E. Lee proved to the American public he possessed such an indomitable trait. No other Union general could match Lee’s ability to repeatedly beat them with fewer men and resources. President Abraham Lincoln saw only one man that possessed such a comprehensive view of the war. That man was Ulysses S. Grant.

Lincoln appointed Grant as general of all armies given his military record out west. His objective was to end the Confederacy, but that meant the end of the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Robert E. Lee. General Lee successfully defeated the Army of the Potomac or evaded capture in 1862 and 1863. He later fought Union General George Meade to a stalemate around Mine Run. President Lincoln needed someone with a comprehensive view or someone that possessed the coup d’oeil to beat Robert E. Lee and his army into submission. Grant proved to be Lee’s equal, and proved time and again that he possessed the rare quality of the coup d’oeil.

Lincoln appointed Grant as general of all armies given his military record out west. His objective was to end the Confederacy, but that meant the end of the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Robert E. Lee. General Lee successfully defeated the Army of the Potomac or evaded capture in 1862 and 1863. He later fought Union General George Meade to a stalemate around Mine Run. President Lincoln needed someone with a comprehensive view or someone that possessed the coup d’oeil to beat Robert E. Lee and his army into submission. Grant proved to be Lee’s equal, and proved time and again that he possessed the rare quality of the coup d’oeil.

Grant applied both Jomini and Clausewitz’s principles of war in the western theater from Belmont to Chattanooga. All of their ideas came naturally to him as “common-sense.” Grant wanted to pressure the Confederate armies at every point, rendering them unable to reinforce one army or the other. He ordered General Franz Sigel down the Shenandoah Valley; Generals George Crook and William Averell moved against the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad; General William T. Sherman marched onto Atlanta from Tennessee; General Benjamin Butler landed on the James River Peninsula with the Army of the James to pressure Richmond; and Grant would be on the field with Meade, as it was his objective to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia.[2] He saw the strategic objective as both the Confederate armies and their supply lines, and he used the coup d’oeil at the strategic and operational levels. He followed strictly to one of Jomini’s essential maxim’s “To throw by strategic movements the mass of an army, successively, upon the decisive points of a theater of war, and also upon the communications of the enemy as much as possible without compromising one’s own.”[3]

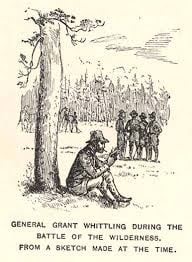

The first engagement between the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia took place at the Battle of the Wilderness. General Meade still retained command of the Army of the Potomac, and while Grant attempted to stay out of tactical decisions, some events would force his hand. Grant received information from the Bureau of Military Intelligence that Longstreet had not yet joined the Army of Northern Virginia, but the Confederate III Corps threatened the intersection of the Orange Plank Road and the Brock Road.[4] On May 5, Grant personally took over the tactical command by issuing orders to Sedgwick’s lead division commander, George Getty, to cull Confederate General Richard Ewell’s movements near the intersection of the Orange Plank Road and Brock Road.[5] During the battle, Ewell’s men bent back the Union line on the turnpike near Grant’s headquarters. One officer approached Grant anxiously, stating the need to move his headquarters further from the line. Grant’s response was decisive as he told the officer to bring forth their artillery to push the rebel line back. Not long after the Confederate attack was repulsed.[6]

During the Grand Review in May of 1865, Grant stood by three-star studded flags emblazoned with the names of “Shiloh,” “Vicksburg,” and “the Wilderness.”[7] It should be no surprise to the military historian that these battles stand among his greatest victories. He snatched the initiative from Lee and never relinquished it. J.F.C. Fuller rightfully stated, “Strategically, it was the greatest Federal victory yet won in the East, for Lee was now thrown on the defensive – he was held. Thus, within forty-eight hours after crossing the Rapidan, did Grant gain his object – fixing Lee.”[8] Grant displayed a strength of mind during the battle which Clausewitz described as “a strong mind is one which does not lose its balance even under the most violent excitement.”[9] Apart from being able to decisively seize the initiative after the battle of the Wilderness, Grant could see the calm through the storm. He did not let the hysteria of battle drive his decision as so many others had fallen victim to. Nonetheless, calmness in battle without being able to see the objective is impractical. It is the strength of mind that made it easier for him to refine his decision-making. This trait only becomes more evident as the Army of the Potomac marched onto Spotsylvania Courthouse.

Bibliography

Bartholomees, J. Boone. U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues: Theory of war and strategy. Washington D.C.: Defense Department, 2012.

Catton, Bruce. A Stillness at Appomattox: The Army of the Potomac Trilogy. New York: Doubleday, 1953.

Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Translated by J.J. Graham. New York: Digireads Publishing, 2018.

Feis, William. Grant’s Secret Service: The Intelligence War from Belmont to Appomattox. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Fuller, JFC. Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Grimsley, Mark. And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May-June 1864. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Jomini, Antoine Henri. The Art of War: Strategy & Tactics from the Age of Horse & Musket. London: Leonaur Publishing, 2010.

Rhea, Gordon. The Battle of the Wilderness. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

White, Ronald C. American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Random House, 2016.

[1] Antoine Henri Jomini, The Art of War: Strategy & Tactics from the Age of Horse & Musket, (London: Leonaur Publishing, 2010), 285.

[2] Mark Grimsley, And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May-June 1864, (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 4.

[3] J. Boone Bartholomees, U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues: Theory of war and strategy, (Washington D.C.: Defense Department, 2012), 22.

[4] William Feis, Grant’s Secret Service: The Intelligence War from Belmont to Appomattox, (Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 201.

[5] Gordon Rhea, The Battle of the Wilderness, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994), 133.

[6] Bruce Catton, A Stillness at Appomattox: The Army of the Potomac Trilogy, (New York: Doubleday, 1953), 87-88.

[7] Ronald C. White, American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant, (New York: Random House, 2016), 417.

[8] JFC Fuller, Grant and Lee: A Study in Personality and Generalship, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), 215.

[9] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, translated by J.J. Graham, (New York: Digireads Publishing, 2018), 57.

I thought (based on the title of this piece) that it was maybe the beginning of an insightful series on this campaign. But this is nothing but a Grant ‘love fest’ with a sprinkling of secondary sources to bolster the writer’s opinion that ‘Unconditional Surrender’ Grant was peerless and invincible. So apparently when Grant was chosen by Lincoln, Lee should have just broken his sword over his knee and rode Traveler back to Richmond. The author is promulgating pure speculation – “Grant applied both Jomini and Clausewitz’s principles of war in the western theater from Belmont to Chattanooga. All of their ideas came naturally to him as “common-sense”. So Grant just intuitively knew and applied European military maxims?! Lee graduated 2nd in his class – 14 years before Grant. Who would have had the better grasp of military principles? There’s more – “He snatched the initiative from Lee and never relinquished it.” What about North Anna? Also, who’s not aware of the bias in Fuller’s writings – but somehow he’s quotable? Certainly there is a minimum factual standard for published pieces and someone reads these before publishing under the ECW moniker. If a historical essay is primarily an opinion piece, please just label it as such (at the beginning). If you want a ‘comprehensive view of the Overland campaign’, stick with Gordon Rhea and William Matter.

The “Comprehensive View” is another short definition of the coup d’oeil. That is my argument. Grant possessed it. Lee also possessed such a gift. My intention here is not to downplay Lee’s role, but this article is about Grant’s decision-making, not Lee’s. Keep in mind Lee fought Grant to a standstill in every battle. The reason why the Wilderness is labeled as a “Strategic Victory” is because Grant does take the initiative away from Lee. And Lee does rightfully attempt to retake it throughout the campaign. He does it time and again. He attempts to take it away at Spotsylvania, North Anna, and most importantly Cold Harbor. Secondly, I do not contend that Grant knew that he applied such theories. The reason both him and Lee were the only two generals that could apply these maxims as “common-sense” is because they could see past the fog of war more easily than their subordinates. However, this is not a Grant v. Lee article. The application of military theories helps historians interpret sound decision-making amongst 19th century generals. Finally, this article is not to ignore Grant’s mistakes either. Whether I believe it was right to engage Lee in the Wilderness or not, it still was a bold plan and went against the writings of Clausewitz.

I did not know Grant “won” the battle of the Wilderness. I think the consensus of historians is that this was a drawn battle, not a victory for Grant.

“Strategic” not tactical. I base my interpretation off the analysis of JFC Fuller who was a British military theorist. He also went into his research with the notion that “Grant was a butcher.”

I appreciate Nathan’s perspective and feel he’s made some very valid points. The notion that Grant “fixed” Lee at the Wilderness makes sense. It also makes sense that Lee was thereafter “fixed” by Grant, for even though Lee made a number of tactically offensive moves in the months ahead, he was essentially playing defense. That, I think, is what makes the title of Nathan’s article so apt.

A broader research of your same premise. The writing’s interesting. Ewell culled caught my attention and I loved the Catton thrown in… Getting better every time. Keep it up and keep reading.

I disagree with Fuller’s assessment that Grant “fixed” Lee in the Wilderness. That implies that Grant pinned Lee in place in a place to Grant’s advantage. Were that the case, Grant would’ve stayed in the Wilderness and kept slugging it out. Grant had to pick up and move and shake Lee out of place so he could get at him to better advantage.

Grant DID seek to get Lee into a fight, so that much of his strategic plan worked. Once engaged, Grant stayed engaged. Perhaps that’s Fuller’s meaning, and perhaps it’s just the word “fixed” that’s inaccurate.

That is a valid point. I believe what Fuller probably meant to say that Grant took the initiative away from Lee; therefore, it was a strategic victory. The initiative is important which explains why Lee attempted to regain it time and again.

It also could just be a British thing.

Yes, the phrase “took the initiative away from Lee” gives much greater clarity to the point I felt Nathan provided in his original post. And Nathan’s point remains, I think, compelling.

The problem here is that Grant’s operational plans are known, and went badly awry.

Grant expected to fight one battle, swat Lee aside, and march to link up with Butler within 10 days and attack Richmond via the Bermuda Hundred. This of course didn’t happen. Indeed, Grant can within an inch of being bottled up in the Wilderness like Hooker. If not for Longstreet’s wounding and Hancock’s instinctive understanding of the danger, Grant would have been bottled up.

Every time Grant tried to march to join Butler, Lee intercepted. It was Lee who kept taking away Grant’s initiative, not the other way round.

When you count the sheer quantity of forces Grant got (and burnt through), it boggles the mind. Grant had the use of more than 200,000 men (PFD as defined in regulations) north of the James, and close to a quarter of a million men in total.

Rather than any great captaincy, Grant essentially used the army as a battering ram.

A few points here. The first is that Grant did not intend to beat Lee until November (not too far off from the initial timeline of events). Do I think Grant should have had more involvement with Butler? Yes. I think Dr. Grimsley makes an excellent argument in Grant’s Lieutenants. As for Longstreet’s wounding, Gordon Rhea found that his wounding did not have much to do with the fallout of the Confederate assault. It was already slowing by the time of Longstreet’s wounding. Hancock reformed his line and held another assault against Confederate forces. If anything Longstreet prevented disaster on the Confederate right, and he should be given credit for such an offensive action. Nonetheless, the Union left held its own and its flank was well protected under Hancock’s entrenched line. In fact, Confederate forces had to fallback from the wilderness in that area given the fires. Lee does order his soldiers to withdraw from that area and move farther south.

Grant’s operational objective was not Butler. It was to get between Lee and Richmond; therefore, Lee would be forced to attack Grant in an entrenched position. Lee lost the initiative after the battle of the wilderness. If you believe Lee held the initiative, then I think it is important to ask the question, “Why would Lee continuously attack Federal forces if all he had to do was wait for Grant to attack?” It was because he wanted to retake the initiative from Grant. Lee launched many attacks and limited offensives against superior forces with not one succeeding. If Lee held the initiative it puts into question his decision-making and generalship during the Overland Campaign. Which I do not think is the case; Lee’s generalship during the Overland Campaign is astounding.

I don’t think Lee derailed Lee’s initative at all. Yes, he kept jumping into Grant’s way, but that played into Grant’s overall plan of forcing Lee into a fight. Grant is also the one who determined how long the armies stayed at any one battlefield, forcing Lee to react. Certainly Lee’s defensive positions proved problematic for Grant, but Grant ultimately made his own choices about attacking or maneuvering or marching.