Seidule’s Thesis on Lee: Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause

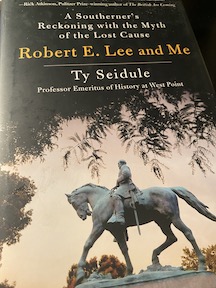

I recently had the chance to read Ty Seidule’s new book Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause. As a Southerner, Seidule grew up in the shadow of Arlington Manor, immersed in a pro-South view of the world and of the war. Hero worship abounded.

I recently had the chance to read Ty Seidule’s new book Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause. As a Southerner, Seidule grew up in the shadow of Arlington Manor, immersed in a pro-South view of the world and of the war. Hero worship abounded.

Seidule carried this worldview well into adulthood, but his profession as a military historian—he’s professor emeritus of history at West Point—took him to some places that were, at first, uncomfortable. Following the facts led him to some surprising and, at times, upsetting realizations about the South’s greatest hero. Here’s his basic premise, laid out clearly on page 9 of the book:

Eleven southern states seceded to protect and expand an African American slave labor system. Unwilling to accept the results of a fair, democratic election, they illegally seized U.S. territory, violently. Together, they formed a new “Confederacy,” in contravention of the U.S. Constitution. Then West Point graduates like Robert E. Lee resigned their commissions, abrogating an oath sworn to God to defend the United States. During the bloodiest war in American history, Lee and his comrades killed more U.S. Army soldiers than any other enemy, ever. And they did it for the worst reason possible: to create a nation dedicated to exploit enslaved men, women, and children, forever.

Seidule isn’t just throwing bombs. The entire rest of the book backs up this perspective—one that he, himself, came to gradually, sometimes grudgingly, by looking at the facts and not the myths, legends, and passed-on tales. His ultimate verdict: “Robert E. Lee committed treason.”

The book has been controversial, especially among Southern partisans and neo-Confederates, but as one friend asked me after reading the book, “Tell me where he’s wrong.” I’ve chewed on that challenge for weeks, which is one of the reasons I’ve not yet written about the book. There is much to chew on if one reads Seidule’s work with the same kind of open mind that he himself had as he confronted facts and hard truths. Lost Causers will object, but Seidule’s journey from their very perspective to where he is now is remarkable.

Robert E. Lee and Me is one of the most important books to come out in years about the way we, as a society, remember the Civil War and what we do about it.

There is a great deal to say about Seidule’s book, but it’s enough for now to say that he is easily refutable on virtually everything he says about Lee. I can’t imagine how he was able to have that book published since some level of editorial integrity is supposed to be maintained.

If a West Point history professor, who’s from Virginia, says he wants to write a book that will cast shade on Robert E. Lee and the Confederacy, modern-day publishers will line up to print it.

To be clear, Seidule has every right to his opinions. He is entitled to them. I’m merely pointing out that there’s a ready market for any Southerner who is willing to insult the Confederacy.

A book which ‘insults’ the Nazi regime would also have a ready market, because, like the Confederacy, it was a disgusting and evil regime.

Since it is so easy, would you please do so? I’d like to see a refutation to Seidule. He is a skilled historian, but of course might either misstate facts (he offers a huge volume of them) or omit facts that undercut his argument. Simply asserting that you can refute him does not help us learn. Thank you.

I wouldn’t hold your breath for a reply. BG Seidule’s book is well written, sourced, and filled with truth. Seidule also sits on the committee for renaming military bases that are named for southern rebels. I myself am a retired Army officer and look forward to renaming those bases that are currently named after traitors against America.

I disagree strongly with you that those U.S. military officers who resigned to serve the Confederate states were traitors. The U.S. Constitution was basically a contract of association between the original 13 states for their mutual benefit (eg. commercial relationships, military defense, etc.). The individual citizen loyalties were primarily to their respective states (formerly independent colonies) and to the United States of America secondarily. These relative loyalties continued for over 100 years, but diminished beginning with the Spanish-American War era. However, the loyalty to America-first was not solidly established until the run-up to, and participation in the Great War (I.e. WWI). When the southern states seceded in the early 1860’s U.S. military officers resigned to serve their respective states which were their top priority. Considering the historical context and slowly increasing loyalty to the U.S.A., it is patently erroneous to label these men as traitors. (I, too, am a former U.S. Army officer from border slave state MIssouri — which did not secede — and a published author on U.S. military history.)

James West. You theory is certainly offered, but it fails to explain why “Lee and Lee alone among the Virginia colonels [in the US Army 1861] left the United States.” Seidule, page 226. Indeed, a significant proportion of West Point and Annapolis trained officers from Southern states opted to stay and fight for the Union. Many of Lee’s immediate and extended family were puzzled by Lee’s choice, and several served on the Union side.

As for the “contract theory” of the Constitution, the argument presumes that if a State seceded, that freed its citizens from any obligations to the United States that they undertook as individuals. Lee’s oath as an officer was made as an individual, not as a representative of Virginia. By your logic, any citizen of Virginia who remained with the Union was the real traitor, by opposing his home state.

One can read the speeches of Danial Webster in the 1840s to show that the change from “United States are” to “United States is” occurred after the War of 1812, well before the Spanish-American War. To be sure, national guard units were generally raised on a state or regional basis, and continue to be so done today. But one would be hard pressed to say that this recruiting tool shows a disloyalty to the United States and preference for state autonomy.

Not a single statement to back up this bald assertion. Because he can’t.

I read the book recently. I have been a Civil War buff for almost 60 years. Over the last few years, I have changed my view from the Confederates primarily fighting for States Rights to preserving Slavery. His book hammered that home for me. Best book I have read in a number of years.

Southern statesmen and newsprint repeatedly stated during secession and during the war that slavery was the “mere occasion” or “immediate cause” of secession, meaning there was a more fundamental cause of secession of which slavery was the most recent example. That fundamental cause was 70 years of Northern infidelity to the compact around which the States were united. That infidelity was spawned by a New England cultural imperialism and a yankee sectionalism and cupidity that sought to dominate the country both politically and economically.

That slavery was not the CS ultimate object is easily proven not just by Southern words but more importantly by Southern actions. “Actions speak louder than words.” Take Lincoln for an example. He was a typical dishonest politician. He first stated, “I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist among them, they would not introduce it.” Then when it became politically expedient he claimed that the South thought “slavery was right and ought to be expanded.” Lincoln sought to play upon Northern racism to coalesce a political following that feared blacks expanding into what was a primarily a lily white North and West. He used this tactic knowing full well that Calhoun and 40 Southern congressmen had in a letter to their constituency, explicitly disavowed any desire to expand slavery. Lincoln was merely playing the slavery card for political gain. This dishonesty was best displayed in his actions which revealed his abstract “antislavery” moralizing held no real humanitarian concern for the slaves. Even his EP was a “war measure” that contained no plan whatsoever to care for the freedmen whom he said must “root hog or die.” His desire to keep slavery out of the territories was no moral line in the sand. He was determined to keep blacks, both slave and free out of the territories, and in doing so keep Southern voters out too. His desire to keep slavery bottled up in the South was a strategy to create an excess of slaves in the South that would eventually lead to their becoming worthless, and no longer supported by the masters. Then they would either “die out” landless and penniless, or at least then Southerners would agree to allowing the black folk they had grown up with to be colonized out of necessity. This is how Lincoln’s actions belayed the true meaning of his antislavery.

It is in this context that Southern “proslavery” must be understood. This is why the Mississippi Declaration of Secession laments that the North “seeks not to elevate or to support the slave, but to destroy his present condition without providing a better.” Southerners believed slavery in the abstract a violation of natural law just as much as Lincoln. But unlike Lincoln, Southerners held a genuine humanitarian concern for the slaves, and knew that natural law also dictated that when the abstract ideal cannot be achieved, you must do what causes the most good and least harm. The slaves were not abstractions to Southerners, they were almost half the Southern population who lived cheek to jowl with them on a daily basis. And given the corner into which the North had backed the South by being unwilling to absorb any of the social costs of allowing freed slaves to migrate North or West, Southern “proslavery” argued that slavery was the best means of managing so large a population of destitute people in a humanitarian and economically feasible manner within the boundaries of the Southern borders alone.

In the case of the South, its actions clarify its words about slavery. There is abundant proof in the actions of the CSA after secession that slavery was NOT the motive for secession. The CSA turned down the infamous Corwin Amendment. It turned down the offer to keep slavery made in the Emancipation Proclamation. It turned down the suggestion at the Hamptons Road Peace Conference that by returning to the Union it could defeat the proposed 13th Amendment ending slavery. Even in words throughout the war, various Southern leaders and newsprint stated explicitly that slavery was not “the cause” for which they seceded and fought. Both in actions and words the South made clear that “preserving and extending” slavery was not its cause. Its cause was INDEPENDENCE.

Another post-secession ACTION proving slavery was not the CSA secession motive is the following corroborating 1861 – 62 evidence from both foreign and domestic sources. As difficult as emancipation was going to be, the South was so determined to gain independence that it was willing to do it even at the high economic and social cost of freeing the slaves and trying to accommodate them within the CS borders alone. The South knew it would need foreign support to win its war for independence. It also knew that a barrier to that support was the institution of slavery. So as early as November of 1861, there is primary source evidence that the South was willing to endure the immense difficulties of emancipation if it meant obtaining recognition and military support from France and Britain.

A British paper called “Once A Week,“ dated Nov. 30, 1861, provides an early indication of Southern willingness to emancipate: “Slavery is doomed, on any supposition; and the Confederate authorities are already saying publicly that the power of emancipation is one which rests in their hands; and that they will use it in the last resort. This is a disclosure full of interest, and hope.” (Slavery, Secession, and Civil War; Charles F. Adams, pg. 304).

Note that this was written only seven months after the war began. If the CS utimate object was “preserving and extending slavery,” would ending slavery even be considered? That would be preposterous!

Additional evidence reveals as the war escalated that the CS considered it “last resort” time, and started making that offer to end slavery as early as 1862. On April 8, 1862 the “South Australian Register” reports: “A Southern Bait.— It is understood, in that indirect but accurate way in which great facts first get abroad, that the Confederacy have offered to England and France a price for active support. It is nothing less than a treaty securing free trade in its broadest sense for fifty years, the complete suppression of the import of slaves, and the emancipation of every negro born after the date of the signature of the treaty. In return they ask, first, the recognition of their independence; and secondly, such an investigation into the facts of the blockade, as must, in their judgement, lead to its disavowal. — ‘Spectator.’” (South Australian Register, Tuesday, April 8, 1862, page 3, BRITISH AND FOREIGN GLEANINGS).

One month later, in “The Daily British Colonist,” page 2, May 29, 1862 we read: “The rumors of interference by France and England in American affairs are received, and it is even asserted that the South, in return for the intervention, will guarantee the emancipation of her slaves.”

From these foreign papers we find out something is in the works regarding Confederate emancipation. By July 15, 1862, we find out from a domestic source. Seven Union loyal border State Congressmen write emphatically in a letter to Lincoln that the CS offer to end slavery is reality. Informing Lincoln why they support his own offer for compensated emancipation in the Union loyal Border States, they give the following reason:

“We are the more emboldened to assume this position from the fact, now become history, that the leaders of the Southern rebellion have offered to abolish slavery amongst them as a condition to foreign intervention in favor of their independence as a nation. If they can give up slavery to destroy the Union; We can surely ask our people to consider the question of Emancipation to save the Union.” (Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 – 1916: Border State Congressmen to Abraham Lincoln,Tuesday, July 15, 1862).

These seven Union loyal border State congressmen had no reason to lie to their President in affirming the CS offer to end slavery as a “fact now become history.” Even though such a plan would by nature be highly secretive, these border State congressmen were in a position to find out about such a secret CS plan because the seceded States were in constant contact with them in attempts to persuade them to join the CS cause. Someone in the CS spilled the beans, and now the secret was being revealed to Lincoln. It must be asked is it mere coincidence then that Lincoln had just met with these same border State congressmen on July 12, 1862, and the very next day he drafted his own plan of emancipation with which he surprised Seward and Welles that same day? Is there any doubt that Lincoln’s EP was an attempt to head off this CS emancipation offer and prevent France and Britain from allying with the CS? Food for thought! And this need for secrecy is why we don’t find a Confederate paper trail regarding this offer.

Later on in 1865, we find the same CS offer to end slavery still being made in the Duncan Kenner mission when Lee surrendered. (For further information on the Kenner mission see: http://archive.org/stream/jstor-1915097/1915097). The CSA had all along been willing to end slavery in spite of the great sacrifice it would mean. A sacrifice Judah Benjamin explained as follows: “The sole object for which we would ever have consented to commit our all to the hazards of this war, is the vindication of our right to self-government and independence… For that end no sacrifice is too great, save that of honour.” (Judah Benjamin to John Slidell explaining the Kenner mission, Dec 27, 1864.).

One thing is for certain, this willingness to end slavery proves the South did not secede “to preserve and extend slavery” as the popular narrative claims. Rather, it sought to gain independence from an unfaithful partner, and the fundamental American right to a “government by consent of the governed.”

I am most grateful for your complete, documented, and well written explanation into the never ending question about slavery and the cause and effect it had on the real reason for the Civil War. I know General Lee had great trepidations about giving his loyalty to Virginia or to The United States and suffered both before and long after the War about the decision he ended up making.

You have very carefully identified lots of primary but obscure references to support your argument. You seem to think the multiple official statements justifying secession (other than Mississippi’s Declaration) irrelevant; but should we not pay attention to the reasons actually asserted by the secessionists, which repeatedly placed slavery at the top of the lists? One might also look at the Constitution of the Confederacy, which was patterned after the US Constitution (after all, the South asserted it was the true defenders of the Constitution). The biggest changes were to make slavery an explicit element of the Confederacy. Perhaps a report from an Australian newspaper about a rumored offer from the South to end the war by promising to end slavery in 50 years does indicate flexibility on the issue; but the refusal of Jeff Davis to consider enrolling slaves to fight for the South (in exchange for later freedom) until 1865 shows no flexibility.

I often marvel at the efforts some will go to judge and make aspersions about the veracity of past generations and the decisions they made relevant to them in their time as against the clarity time and distance offer today. Robert E. Lee did not wake up one morning and decide to make war against the United States. It was a terrible, difficult decision he and many thousands of other Americans made. They were deciding where their prime responsibility and loyalty lay ~ with their State or with the Federal Government. The study of Robert E. Lee spells out that he felt his State of Virginia was his first. He would go with whatever direction Virginia went. And I offer that even today there is a great lack of understanding at EVERY level of Government what they can and cannot control over its’ citizens. And that is okay. I have a family portrait of President Ford signing the Official Pardon for Robert E. Lee on the front steps of the Custis Mansion.

I agree with “hardlyharryhere” but will expand on his assessment of Robert E. Lee. The U.S. Constitution was basically a contract between thirteen independent colonies to form a governmental union. However, citizen loyalty was primarily to their respective states, and to the federal Union secondarily. This order of loyalty continued for about one hundred years, changing gradually during the latter 1800’s and completely reversed by the time the U.S. entered World War One. This is why Robert E. Lee and other individuals resigned their U.S. commissions when their states attempted to exit the federal Union. Ty Seidule was ignorant of this underlying, progressive issue of loyalties, or chose to ignore it, when he declared Robert E. Lee a traitor.

It may have been a difficult decision for Lee, but he made his choice. It was to repudiate his oath as an officer. Lots of other southerners who were serving in the US Army made a different decision. I don’t see how it’s being a tough choice makes the choice any more honorable or defensible.

I guess he forgot that Lincoln offered Lee the command of the Union Army!

I grew up in rural Louisiana and have always known the Civil War was about slavery… like, from the time I was 5 years old and was given a copy of the Kurz & Allison prints. That said, I dressed up as a Confederate for Halloween once around the age of 7 or 8, and did have a Confederate battle flag I used to play war with. By the time I was in high school, anybody cool with waving the battle flag was just historically ignorant. The States Rights argument behind the Civil War was still prevalent and probably the most generally believed. I got in a huge, late night dorm room argument, with a friend about why the Civil War happened. He was like States Rights and I was like economics (slavery).

I was a kid in the 80s and early 90s. Finished college in 2000. The funny thing is I stopped reading about the Civil War sometime in my teens and and not again until my 30s. Had no idea the internet and started a black Confederate craze. Before the internet, I already knew there weren’t any black Confederates.

I look forward to reading the book. The Lost Cause mentality has shaped so much history and literature. Faulkner, for example, is the product of the South living the Lost Cause.

LEE COMMITTED TREASON. SOUTH WANTED STATES REIGHTS TO PRESERVE SLAVERYU

If anyone is arguing that the slave states seceded for some other reason than to protect, maintain and even expand slavery: well, that ship has sailed.

Shakespeare wrote there is not true valor in a false cause. I don’t know if that applies to Robert E. Lee or not.

“If anyone is arguing that the slave states seceded for some other reason than to protect, maintain and even expand slavery: well, that ship has sailed.”

And, adults are waving good-bye to that ship, full of shallow-thinkers and immature people. Perhaps, some day, those people will grow up to be adults.

If there is any discussion about the reason for secession one must only read the constitution of the confederate states. Various confederate states that wrote new constitutions placed slavery as a major reason for secession. The V.P. Of the confederacy wrote in hid “cornerstone “ speech about slavery and it’s importance to the south. If it was not so important or a basis for secession then why were those who owned twenty or more slaves exempt from the draft. Why were African Americans in the US Army not treated as equals but killed outright or as Davis and the CSA Congress stated they were to be treated as runaway slaves in revolt against their masters. Slavery was the major factor for secession.There were others yes but not as openly talked about. The press stories quoted in another writing sound good but were they written by pro southern English. I don’t know, I have never seen them before. The English and French governments were probably never going to come in on the side of the south. Their people would not let them, the overall feeling in both countries at the time was against slavery. The lost cause teachings have done nothing good for our country, all they have done is to distort the truth. The idea of the southern cavalier fighting against the unscrupulous northern aggression is based not on fact, but untruths. Lee, Beauregard,Stuart, all of them committed treason, they broke their oaths to the U.S.A. The idea of allegiance to your state first was old and hollow even then. You were either an American first or not.

OK, where do we begin?

“‘Robert E. Lee and Me’ is one of the most important books to come out in years about the way we, as a society, remember the Civil War and what we do about it.”

Why? Why is it “one of the most important books”? And, as for “what we do about it,”—what do YOU think we should “do about it?” (Who is “we,” by the way?) More to the point, WHO decides what “we” do about the Civil War’s legacy?

I think it would be helpful, for those of us regulars on the ECW discussion boards who have Confederate ancestors, to have the ECW braintrust (whoever that may be) define what they consider to be the “Lost Cause.”

It’s obvious that the ECW braintrust considers the “Lost Cause” to be a bad thing. I may agree with you. But, I may not. I am asking for clarification. What is the “Lost Cause?”

Is it the idea that states had the right to decide for themselves, in the mid-1800s, whether to stay in the United States or not? In 2021 that’s an easy question to answer. But, in 1860, it wasn’t. Even Lincoln referred, in at least one of his letters, to the United States as being a “confederacy” of states. Shelby Foote eloquently said in “The Civil War” PBS miniseries that, before the Civil War, many decent Americans said “the United States ARE,” as opposed to “the United States IS.” They thought of the US as a collection of states, instead of one entity.

The Civil War settled that question, forever. But in 1861, when Lee and other Southerners chose to follow their states, instead of their nation, it wasn’t settled. And professional historians should know that. Especially professional historians who train the men and women that lead the most powerful Army the world has ever seen.

A shallow understanding of history is a BAD understanding of history. No matter how many books it sells, or how many 5 star ratings it gets on Amazon.

I, for one, disagree with those who felt that, in 1860, they had the right to leave the United States. But, disagreeing with someone is NOT the same thing as saying that they were “wrong.” Sam Watkins said that, even after the Civil War, he felt that the southern states had the right to secede. He thought it was the wrong thing to do, but they had the right to do it.

History is complicated, isn’t it?

Well said!

History is certainly complicated, but the basic elements of the “lOst Cause” are pretty well established. While hardly a definitive or always reliable source, one can look that the list of tenets of the Lost Cause on Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost_Cause_of_the_Confederacy#Tenets

Many of these tenets show up in the comments to this post: the South did not secede because of slavery; the Constitution was a mere contract from which a state might withdraw if it felt its rights were offended; the North was the aggressor; Southern honor was never defeated. Even the notion that slavery was benign is restated above: “Southerners held a genuine humanitarian concern for the slaves.”

If you don’t know what the “Lost Cause” means, you might try reading a bit about it.

It would be nice if ECW hosted a post that lays out why Confederate soldiers and generals deserve at least some level of respect in modern times. If no ECW frontpager can bring her/himself to write it, then bring in a guest poster. As we’ve all seen, ECW has no problem finding guest posters who think poorly of the Confederacy. Every three months or so, we all see another review for another book that tells us why the Confederacy was bad.

I’m struck by the inability (or unwillingness) of ECW to present both sides of this issue. Especially since it’s obvious that many of us have Confederate ancestors whom we respect for a variety of reasons. (Does that make us “Lost Causers?”)

Here’s why this is a problem: It’s one thing to say that the Confederacy was bad. I say that. But, it’s quite another to say that “all Confederates were bad.” If you only talk about the negatives of one side of an issue, pretty soon people presume that there’s nothing positive about that side at all.

As a published author I am interested in the Civil War from a purely historical basis and write accordingly. I have no interest in articles and publications in which the author’s personal biases override objectivity.

First, Seidule isn’t writing an analysis of what happened at the Battle of X or the Y Campaign – it’s his account of his own views and how/why they changed. I also assume that you apply your lack of interest to the work of Shelby Foote.

You missed my point.

I don;t believe I missed the point as you articulated it.

” I have no interest in articles and publications in which the author’s personal biases override objectivity” – hence my question about Foote.

I love the idea, Don. But I don’t think that ECW, or any other site for that matter is going to be too interested in hosting a post citing reasons why anyone associated with the CSA deserves any measure of respect. To do so would be to subject one’s self to the cancel culture and immediate accusations of racism. There arena for open debate and the civil exchange of ideas is growing smaller in the U.S.

I agree that one cannot leap from the idea that the Confederacy was bad to the idea that all Confederate were bad. We know from studies of soldiers in many different wars that the motivation to volunteer to fight for one side of the other can come from the noble (patriotism, loyalty, “My Country right or wrong, but my country”) to the merely human (peer allegiance, peer pressure, the chance to get a way from home or have a great adventure, or only to get a paycheck). Moreover, we cannot assume everyone volunteered; the Confederacy instituted a draft well before the Union did.

Seidule is not the first to write about a journey of this sort. Charles Dew wrote a similar book: “The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History, and the Slave Trade.” I’m older than Seidule but have made a similar journey over the past 40 years.

As for the merits of much of the background material, we can let the men and women of the period speak for themselves:

http://www.civilwarcauses.org/

A great summation and reference and I thank you for that. As Seidules’ book states he grew up living near the Arlington Manor I guess I have him one better as I grew up in the direct family of General Lee. My Aunt Mary was his Grand Daughter and the daughter of Robert E. Lee, Jr. If only historians took time to fully understand the times that generation lived through and make their decisions, for or against, given the light of reflection, one might better appreciate their reality.

Authors and others gain insight from their studies, training, experiences and others, and the objective ones form their conclusions accordingly. In other words, they are data / information driven, and do not endlessly strive to prop up some pre-conceived, ill-considered notion.

When you speak of a “pre-conceived, ill-considered notion,” you are course referring to the “Lost Cause” narrative, right? If otherwise, there is a (large) boat-load of material to throw your way. We can start with the many period documents archived on the website I cited above. Feel free to tell me how they are wrong.

“endlessly strive to prop up some pre-conceived, ill-considered notion”

If you think that’s what the author does in this particular book, you should have read it first – or you did and simply misunderstood it.

I was not referring to Seidule’s book content in my response, but to a particular type of Southern apologists. The only issue I took with Seidule was him calling Robert E. Lee a traitor. which was quoted in a posting, and I spoke to that in an early post. Further, it had nothing to do with my very deep Virginia roots on both sides of my family which, in one instance, dates back to 1619.

No, I was not referring to the “Lost Cause” narrative,

Whenever I see an ECW topic involving secession, slavery, and the Lost Cause, I know I am in for a lively debate!

It seems that both sides of the arguments want to further their belief by citing or quoting facts, and believe their facts are irrefutable. What I believe is that most facts are still subject to interpretation, and I must say I am swayed by both side’s interpretations. So in the case of Lee, one day I am swayed he is a traitor, and then a comment is posted that makes me reconsider.

Unfortunately, much like today’s political climate, when there is disagreement over one side or the other’s interpretations, the debate quickly devolves into name calling and insults. I wish we could all just respect each other’s opinions, and as is said: agree to disagree.

I also believe these questions will never be settled. The people of the North and South simply come from such different backgrounds, cultures, beliefs, etc. that coming together is very difficult. My reading of US history indicates these differences go all the way back to the founding of the country. Today, we add to the “stew” diverse cultures and backgrounds that just add to the original problem.

I will leave for my fellow posters a prescient quote from Jefferson Davis that to me sums up most civil war arguments.

“A question settled by violence, or in disregard of law, must remain unsettled forever.”

I read a book by Michael Gorra called The Saddest Words. It dealt with theinfluence of the South and the Lost Cause on Faulkner’s writings. As someone who’s lived in the South and North, and soldiered in Tidewater, Va., I have many influences on my thinking. I find myself reluctantly tolerant of the Lost Cause thinking as after theft rationalizations that we all do at one time or another, and therefore, I accept it knowing I cannot change the thinking.

The paramount issue of the period was what is to be done about slavery in U.S. territories. The founders had resolved that in the Land Ordnance of 1787, it was banned. When the Missouri Compromise came up to resolve the Louisiana Territory on the question, they gave a boundary. The 36,30 was to be end of it. It went against the vision of the Founders to an extent yet that generation was soon to be gone. Then came the Mexican-American War. The Compromise of 1850 which would soon be followed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed which made the topic for the time being a matter of Popular Sovereignty. This went against the intent of the Founders. It opened the door for further territorial claims by slave powers. It began the bleeding with skirmishes in Kansas. There was significant economic insensitive to it considering that by the early 1860s, the slave industry was worth 3.5 billion dollars. The Taney Court was in full support the institution based on the Scott ruling early in 57. All was going well for the slave power until the 1860 election where a 3rd party claimed power of the White House as well as seats in Congress on a platform of preventing the spread of slavery in U.S. territories.

The actions of the deep south 7 states was in a defense of this slave labor economic system. The 4 states joining the CSA after Ft. Sumter was the result of the Lincoln’s Administration resolve to muster 75,000 troops to answer for the assault on Ft. Sumter.

General Lee made his decision the way he saw fit. He did this on his own free will. He was fully aware of his actions. The General would be granted a full pardon after his passing close to a century later which absolved him of actions committed against the government.

Amazing comments generated by the post and by this book. I am not a Civil War Historian or an expert on this topic. I did read about half of the book and it seemed to me that we have a man who enjoyed all the benefits of being part of the white, elite class living in the south. and now that he has all the rewards he feels guilty about it. He writes of living in a small town in GA and being in high school when a black man is lynched outside of town. He says he or his friends knew nothing of this event and he learned of it much later. Really?

Thanks, Chris, for posting this review.

fdamaven, your argument with my most recent posting does not hold water. Why Lee resigned and served his home state of Virginia was purely his decision. I pointed out initial colony and state orders of priority which gradually changed over about a 100 year period. This may have been a significant factor in Lee’s difficult decision. As far as the U.S. Constitution, it is a contract in every sense of the word. Further, there is no exit clause, and a Civil War was fought over that issue. The key elements of my posting includes points reviewed by several very knowledgeable individuals, and they all concurred with my analysis.

I don’t know what point you were trying to make about the “National Guard” which came into being after the Civil War, replacing state militias.

James West, I’m sorry if I was unclear, so let me try again. Under the Constitution, individuals were citizens concurrently of the United States and of the state of their residence (not necessarily of their birth). Whatever the legal right of a state to secede (a point I’m not debating here), I don’t see that the secession of a state means automatically that the citizens of that state are no longer citizens of the US and have no obligations to the US — particularly obligations arising through an individual commitment made to the federal government (like the oath of an officer who was educated and employed at the expense of the federal government). Your argument seems to be that, because Virginia had seceded, Lee was no longer a US citizen and thus could not commit treason, nor did he owe any loyalty on a personal level to the United States. At least, that is how I perceive your argument.

So let’s take this logic one step further. How does one describe the decision of other Virginians to fight against that State under the banner of a “foreign nation”, the US? Would they be mercenaries? More pointedly, were they “committing treason” against their own “country” (I.e., Virginia)?

To your argument that people’s loyalties were to their state, not the United States, and that that justifies Lee’s choice, I find only limited historical support for that. It certainly does not apply to David Farragut or David Hunter (among many Southerners who stood with the Union) or, say, people like John Pemberton (a Pennsylvanian who fought for the Confederacy). I think the motivations of men and women at that time were much more complex and layered with conflicting values. To latch onto one factor (whether loyalty to a state or a fervor for abolition) is too easy a way out. Lee made a choice, and can fairly be judged by the choice he made.

You are making this overly complicated. All I was trying to point out was that individual loyalties were, initially, foremost to their colony/state and secondarily to the United States, a historical fact, from the beginning of the U.S. Constitutional acceptance, and this order of priority continued to some diminishing degree for about 100 years. Nor did I intend to imply that Robert E. Lee believed that the secession of Virginia revoked his U.S. citizenship. (I have never heard that argument before.) He made a personal decision which, so far is know, was unrelated to what others opted to do.

This statement is just lost cause mythology. Most Americans at the time of the outbreak of the civil war viewed themselves as Americans first. BG Seidule points out in his book that of 6 southern born colonels in the US Army at the outbreak of the civil war Robert E. Lee was the only one to resign his commission.

In fact his cousin, Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee, also a Virginian had this to say when asked why he stayed loyal to America, “ When I find the word Virginia in my commission I will join the Confederacy.”

Lee took an oath(very similar to the one I took when I received my commission) of loyalty to America. He betrayed that oath when he took up arms and killed Americans. He is a traitor to this country and should be remembered as such.

I took the same oath when I was commissioned. However, your knowledge of 19th Century culture and history is weak.

James West, your argument seems to have been that (1) the Constitution was a contract between individual states and (2) there was then a higher loyalty to individual states than to the national government. Therefore, Lee’s decision cannot be called treason. I asked whether Lee remained a citizen of the US after Virginia seceded, and you say he did. As a US citizen, Lee, by levying war against the United States, committed treason as defined in the US Constitution.

Sorry to be legalistic about this. You might be better off arguing that secession by a state terminated not only the state’s contractual obligations to the US, but also ended the US citizenship of citizens of that state. I admit i have not seen this argument made before, but it is the only way you can make Lee’s decision and subsequent command of Confederate forces not treason.

fdamaven et al, The Constitution has no provision for exiting the federal Union, and a Civil War was fought over this issue. The Constitution document is, in the truest sense, a contract, and more than one qualified lawyer has agreed with me on this point. These petty assertions and arguments are trivial and a waste of time. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion, right or wrong. Sayonara.

I’d be interested in knowing the backgrounds of the attorneys who have given an opinion that it’s a mere “contract”. Thanks.

John,

No one said that it was a “mere contract.” Use of the adjective “mere” is inappropriate in this description.

All right – that means that it must be more than a contract. So what is it?

The Constitution is a contract in the legal sense — and a highly important one.

Could you provide a citation for the claim that the Constitution is a contract? It has been a long time since I was in law school, so my memory is hazy on this.

Two or three practicing lawyers have verbally agreed with me on the Constitution being a veritable contract. I do not know of a published source on this. I will let you research this issue. If it is not a contract in the strictest sense of the word then what is it?

As I have stated previously, in the beginning of the United States of America, individual personal loyalties to their respective states, were greater than to the U.S.A., and this gradually changed over the next 100+ years. This is a cultural fact.

James West, although two or three practicing lawyers may have agreed with you that the Constitution is a contract, I have not seen it referred to that way in any binding legal sense. You ask what it is if it is not a contract, and the answer would be that it is a constitution.

Just as a law is not a contract, so too a constitution is not legally a contract. Perhaps you have heard it referred to in a metaphorical or propagandist sense as a contract, but it is not legally a contract anymore than the 1990s Contract With America was a legal contract.

The U.S. Constitution says in its Preamble that it was “We the People” who created the Constitution. Generally a contract is made between two or more people. If there is a breach of contract one party to the contract can sue the other party to enforce it. If a breach of the Constitution occurred, would an individual citizen sue all the other citizens to try to enforce it?

If you live in a state in the United States, then your state has a constitution. Do you think of your state constitution as a legal contract?

Patrick, Thank you for your informed comment. It is interesting and helpful.

No problem. As I said, the term contract is often used as a metaphor for a variety of things that are not really contracts.

Patrick, One other comment; Merriam-Webster defines “contract” as “a binding agreement between two or more persons or parties; esp: one legally enforceable.” Sayonara

This is an interesting thread. Yes, the US Constitution is the product of an agreement process (ratification) by which states bound themselves and their citizens to duties and obligations, in exchange for rights and privileges. One might consider the process akin to entry into a contract, but the statement of rights and duties stood outside the contract. Think of an agreement to be bound by an arbitration judgment, before the judgment is entered.

I agree that state constitutions are a conundrum under the contract theory. Who are these contracts with? They aren’t contracts at all. Rather, they prescribe the powers and duties of state governments.

One problem with the theory of the US Constitution as a “contract” is that it implies one state has a right to terminate the contract if another state, group of states, or product of the Constitution (I.e., the federal government or any branch thereof) commits what the one state deems to be a breach of the contract. That is, secession was justified when Lincoln was elected because the seceding states believed Lincoln would cause the federal government to abolish slavery. Lincoln had not been sworn in when the first states seceded, so no plausible breach had actually yet occurred. So even under the contract theory, secession was not justified.

The whole notion of a terminable agreement asserted by the seceding states was tested by the Civil War. The Union won; secession was not permissible.

James that is why a constitution is not a contract. Who are the two or more parties? “We the People”? “We the People” and who?

fdamaven, just to add to what you wrote, the Constitution could have begun with the Preamble “We the State.” It does not. Instead of sending the proposed Constitution to the state legislators for ratification, it was ratified by separately elected conventions in each state so that it would be a product of The People, rather than the state legislators or governors. Now of course The People excluded women, blacks, Native Americans, etc, but the idea was that the Constitution was not created by the King, or God, or the Congress. It was a product of “We The People.” Really brillian insight by the Framers.

Patrick, you are spot-on about the brilliant insight by the Framers. Thomas Jefferson, of probable genius intellect, was a prime mover in this group. It was reported that he drafted the Declaration of Independence in three days and then spent about two weeks to edit it. President Kennedy once commented, in so many words, to a group of top advisors at a meeting in the White House that their combined intellects were exceeded in the same room when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

On March 4, 11861, a prominent 19th Century lawyer spoke of the idea that the US Constitution was a contract:

I hold, that in contemplation of universal law, and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments. It is safe to assert that no government proper, ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination. Continue to execute all the express provisions of our national Constitution, and the Union will endure forever—it being impossible to destroy it, except by some action not provided for in the instrument itself.

Again, if the United States be not a government proper, but an association of States in the nature of contract merely, can it, as a contract, be peaceably unmade, by less than all the parties who made it? One party to a contract may violate it—break it, so to speak; but does it not require all to lawfully rescind it?

Descending from these general principles, we find the proposition that, in legal contemplation, the Union is perpetual, confirmed by the history of the Union itself. The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution, was “*to form a more perfect union*.”

But if destruction of the Union, by one, or by a part only, of the States, be lawfully possible, the Union is *less perfect* than before the Constitution, having lost the vital element of perpetuity.

It follows from these views that no State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union, — that *resolves* and *ordinances* to that effect are legally void; and that acts of violence, within any State or States, against the authority of the United States, are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances.

I therefore consider that, in view of the Constitution and the laws, the Union is unbroken; and, to the extent of my ability, I shall take care, as the Constitution itself expressly enjoins upon me, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States. Doing this I deem to be only a simple duty on my part; and I shall perform it, so far as practicable, unless my rightful masters, the American people, shall withhold the requisite means, or, in some authoritative manner, direct the contrary. I trust this will not be regarded as a menace, but only as the declared purpose of the Union that it *will* constitutionally defend, and maintain itself.

In doing this there needs to be no bloodshed or violence; and there shall be none, unless it be forced upon the national authority. The power the confided to me, will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property, and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion—no using of force against, or among the people anywhere. Where hostility to the United States, in any interior locality, shall be so great and so universal, as to prevent competent resident citizens from holding the Federal offices, there will be no attempt to force obnoxious strangers among the people for that object. While the strict legal right may exist in the government to enforce the exercise of these offices, the attempt to do so would be so irritating, and so nearly impracticable with all, that I deem it better to forego, for the time, the uses of such offices.