Henry Adams on Adam Badeau and Ulysses S. Grant

On April 29, 1885, as Ulysses S. Grant was in the last stretch of writing his memoirs—and in the last stages of his terminal throat cancer—a story appeared in one of the New York newspapers that claimed Grant was not the author of his memoirs at all. “The most the general has done upon the book has been to prepare the rough notes and memoranda for its various chapters,” the paper said.

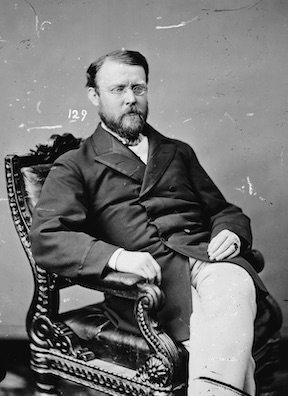

The real author, said the story, was Grant’s aide and former military staffer, Brig. Gen. Adam Badeau. Badeau, a former New York theater critic, a professional writer, and the author of the three-volume Military History of Ulysses S. Grant, was indeed helping Grant on the memoirs, but he was serving more as a sounding board and fact-checker than anything else. However, Badeau refused to refute the story and actually tried to blackmail Grant over it. Grant promptly fired Badeau and went on to finish the memoirs without Badeau’s help or feedback.

Years earlier, during Grant’s presidency, Badeau had lived for a time in a boarding house with the writer Henry Adams, grandson and great-grandson of presidents. In his Education of Henry Adams, written in 1905, Adams reflected back on his acquaintance with Badeau—who was by then ten years in the grave—and Badeau’s impressions of Grant. “Badeau’s analysis was rather delicate,” Adams noted.”

As Adams recounted it, Badeau had taken the lower suite of rooms at the boarding house, Adams wrote:

and, as it was convenient to have one table, the two men dined together and became intimate. Badeau was exceedingly social, though not in appearance imposing. He was stout; his face was red, and his habits were regularly irregular; but he was very intelligent, a good newspaper-man, and an excellent military historian. His life of Grant was no ordinary book. Unlike most newspaper-men, he was a friendly critic of Grant, as suited an officer who had been on the General’s staff. As a rule, the newspaper correspondents in Washington were unfriendly, and the lobby skeptical. From that side one heard tales that made one’s hair stand on end, and the old West Point army officers were no more flattering. All described [Grant] as vicious, narrow, dull, and vindictive.

Badeau, who had come to Washington for a consulate which was slow to reach him, resorted more or less to whiskey for encouragement, and became irritable, besides being loquacious. He talked much about Grant, and showed a certain artistic feeling for analysis of character, as a true literary critic would naturally do. Loyal to Grant, and still more so to Mrs. Grant, who acted as his patroness, he said nothing, even when far gone, that was offensive about either, but he held that no one except himself and [Grant’s former Chief of Staff, John] Rawlins understood the General. To him, Grant appeared as an intermittent energy, immensely powerful when awake, but passive and plastic in repose. He said that neither he nor the rest of the staff knew why Grant succeeded; they believed in him because of his success. For stretches of time, his mind seemed torpid. Rawlins and the others would systematically talk their ideas into it, for weeks, not directly, but by discussion among themselves, in his presence. In the end, he would announce the idea as his own, without seeming conscious of the discussion; and would give the orders to carry it out with all the energy that belonged to his nature. They could never measure his character or be sure when he would act. They could never follow a mental process in his thought. They were not sure that he did think.

Badeau took Adams to the White House one evening to introduce the writer to the president and Mrs. Grant. Adams, who met a dozen presidents in his lifetime and was intimately familiar with some of them, found Grant “the most curious object of study among them all,” adding, “About no one did opinions differ so widely.”

Adams found it difficult to formulate an opinion of Grant. The nearest comparison he could make was to Italian General Giuseppe Garibaldi, who brought about Italian unification. “In both,” said Adams:

the intellect counted for nothing; only the energy counted. The type was pre-intellectual, archaic, and would have seemed so even to the cave-dwellers. . . .

In time one came to recognize the type in other men, with differences and variations, as normal; men whose energies were the greater, the less they wasted on thought; men who sprang from the soil to power; apt to be distrustful of themselves and of others; shy; jealous; sometimes vindictive; more or less dull in outward appearance; always needing stimulants, but for whom action was the highest stimulant — the instinct of fight. Such men were forces of nature, energies of the prime . . . but they made short work of scholars. They had commanded thousands of such and saw no more in them than in others. The fact was certain; it crushed argument and intellect at once.

Adams did not feel Grant as a hostile force; like Badeau he saw only an uncertain one. When in action he was superb and safe to follow; only when torpid he was dangerous. To deal with him one must stand near, like Rawlins, and practice more or less sympathetic habits. Simple-minded beyond the experience of Wall Street or State Street, he resorted, like most men of the same intellectual calibre, to commonplaces when at a loss for expression: “Let us have peace!” or, “The best way to treat a bad law is to execute it”; or a score of such reversible sentences generally to be gauged by their sententiousness; but sometimes he made one doubt his good faith; as when he seriously remarked to a particularly bright young woman that Venice would be a fine city if it were drained. In Mark Twain, this suggestion would have taken rank among his best witticisms; in Grant it was a measure of simplicity not singular. Robert E. Lee betrayed the same intellectual commonplace, in a Virginian form, not to the same degree, but quite distinctly enough for one who knew the American.

Grant “fretted and irritated” Adams for a variety of reasons, not least of all because he became “more perplexing at every phase.” The president proved to be as enigmatic to Adams as he proved to be to almost everyone else.

Adams’s autobiography would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize and stands—along with Grant’s memoirs—as one of the finest works of American nonfiction. You can read The Education of Henry Adams for free online here. You can read The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant for free online here.

Badeau, meanwhile, would never recover from the scandal, although he tried to redeem his sullied reputation after Grant’s death with a fawning book, Grant in Peace: From Appomattox to Mount McGregor. You can read it for free online here.

For more on the saga of Grant’s memoirs, check out Grant’s Last Battle: The Story Behind the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant from Savas Beatie.

Thanks for exposing the existence of other authorized biographies of General Ulysses S. Grant besides his Personal Memoirs. It is of value to read and compare the works of Grant, Badeau, and Henry Coppee (USMA Class of 1845) and take note of how Grant’s story, of the same events, evolves over time. Luckily, the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion and The Papers of U.S. Grant are also available. Here is Coppee’s work of 1866, “Grant and his Campaigns” https://archive.org/details/granthiscampaign01lccopp/page/n5/mode/1up

Thank-you for these intriguing snippets from Henry Adams. It seems as if Adams rated the intelligence of military men rather low, but I can’t see him as a battlefield leader. That is not to disparage him; it is simply to reflect upon the different types of intelligences and their successful applications.