A Comprehensive View of the Overland Campaign, Part III

Part of a Series – Part I and Part II

The Center of Gravity Lies at Ox Ford

Ulysses Grant suffered terrible casualties in the fighting around Spotsylvania Courthouse, and his periphery strategy failed. General Franz Sigel retreated from the Shenandoah Valley, and Benjamin Butler was “bottled up” on the James River peninsula. Only the Army of the Potomac managed to keep advancing further into enemy territory despite high casualties. Grant continued to shift his forces to the North Anna River, looking to get between the Army of Northern Virginia and Richmond. The Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee withdrew from their old lines at Spotsylvania Courthouse. They met the Army of the Potomac near Hanover Junction on May 23, 1864. This position served as a supply junction for the Army of Northern Virginia, and it was an essential target for Grant and his army.[1] Grant’s operational objective remained the same, destroy Lee’s army or negate its offensive capacity.

Lee failed to read Grant’s intention, which had disastrous consequences for his army on May 23 as he sat on the porch of the Fox house drinking buttermilk. Lee remained confident that his opponent was only making a feint near their position. He and his staff sat idle, and Lee had a moment of rest from the misery of dysentery. Nevertheless, Grant gave him no rest. A cannonball flew a couple of feet by him, lodging itself in the brick door frame without notice. Another cannonball flew overhead, destroying the chimney of the Fox House, killing a man next to Edward Porter Alexander.[2] Realizing the imminent danger of his army, he got up and immediately got to work. One of the characteristics of a military genius to Clausewitz is the ability to keep calm in the face of danger.[3] Lee’s coolness in battle was a key characteristic of his battlefield success.

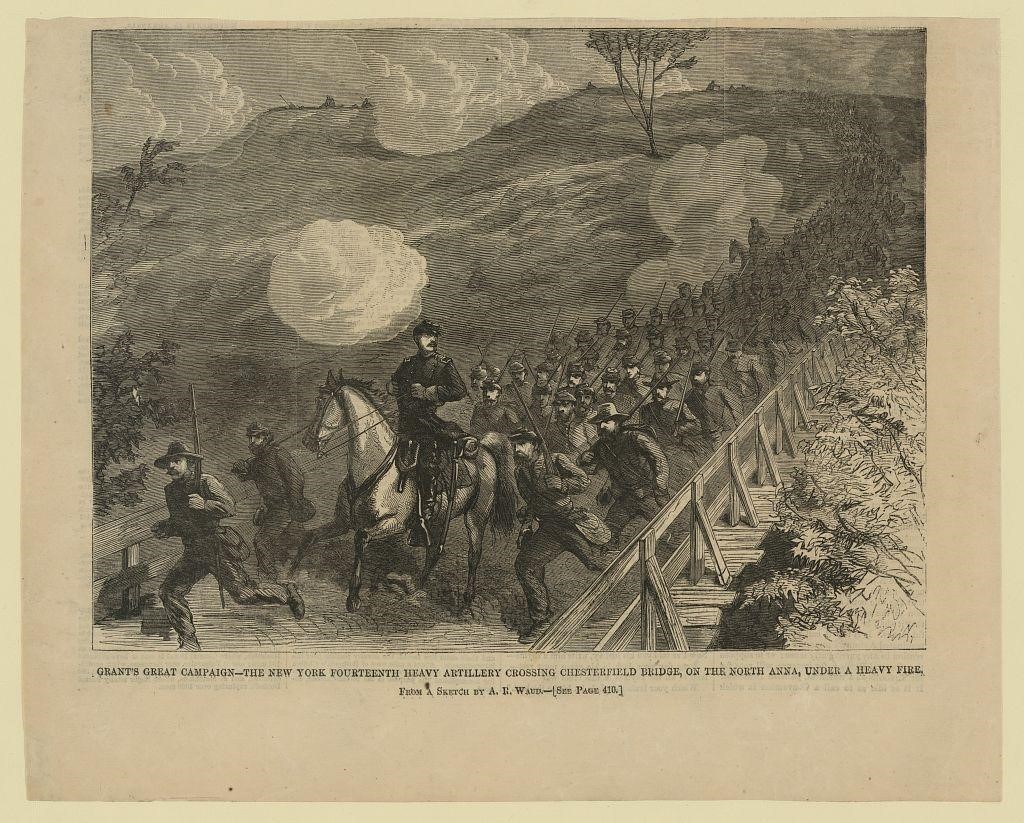

Before Lee’s position was bombarded, Meade had sent a dispatch to Grant asking if Hancock should press forward across New Bridge after using “mass force” to take Henagan’s Redoubt near New Bridge. The Army of the Potomac used overwhelming numbers to break up the small Confederate defenses near New Bridge. They used the same mass of troops near another position northwest of there at a place called Jericho Mills. Grant’s response was direct, “By all means. I would have Warren cross all his men tonight, and intrench himself strongly.”[4] On May 23, Grant applied a fundamental theory of war from Antoine-Henri Jomini, “Take advantage of every irregularity of the ground to get cover for the troops, and keep them sheltered as long as possible.”[5] It was as if he advanced to besiege the enemy and prevent Robert E. Lee from launching a counter-attack to retake the initiative. The initiative led to a tactical victory on May 23; however, it left Grant in a precarious situation.

His forces were now backed up against the North Anna River like the Russian General Levin Bennigsen before Napoleon bagged his army at the Battle of Friedland in 1807. Clausewitz wrote about crossing rivers, “Whether he meditates bringing on a decisive battle after crossing, or may expect the enemy to attack him, he exposes himself to great danger; therefore, without a decided superiority, both in moral and physical force, a general will not place himself in such a position.”[6] At this point, the Army of the Potomac did not possess great numbers of men. Though it may explain why Grant pushed Burnside to take the fortified position of Ox Ford on May 24.[7] It would combine Union forces between Hancock’s Second Corps on the Union left with Warren’s Fifth Corps on the Union right.

The Army of the Potomac was made up of 67,000 men, while the Army of Northern Virginia was reinforced and now had 52,000 effectives under Lee’s command.[8] Grant did put himself at risk, and Lee utilized the river effectively against Grant’s divided forces like Eugène de Beauharnais at the Battle of the Mincio River in 1814.[9] Lee’s ability to adapt to dire situations places him among the great captains of the age. On May 24, he established a new line against Union forces in the shape of an inverted V. The apex sat at the critical position of Ox Ford, driving a wedge between the Union army. After the terrible tactical defeat at Jericho Mills the previous day, Lee scolded A.P. Hill, “Why didn’t you throw your whole force on them and drive them back as Jackson would have done?”[10] The Confederates failed to retake Jericho Mills, but Lee continued to look for an opening in the Union line. Lee sought to strike a blow against II Corps, or is this claim by a subordinate a part of a more prominent myth?

Charles Venable remembered that Lee sought to retake the initiative from Grant by striking against the divided II Corps.[11] However, there are no other sources that corroborate this claim; therefore, it is doubtful that Lee did seek to strike the Union forces at this time. Historians that claim Lee wanted to strike at the divided Union force rightfully point out the necessity of the initiative. If any myth of Marse Lee were true, it would be the story of launching an offensive against the Union army because the Federal forces would have to cross the river twice to reinforce Hancock.[12] Mark Grimsley makes a valid claim that such an attack would be risky as Lee had limited reserves and Hancock was already well entrenched. It was rare for an assault to be carried out successfully. Breastworks defined victory during the Overland Campaign as they did during the battle of North Anna. In James Falkner’s work on Marshal Vauban and the Defense of Louis XIVs France, he states the purpose of entrenchments,

Works and redoubts serve for a retreat to the workmen if an enemy should make a sortie upon them; for being retreated into the said redoubts, they may resist an enemy, and stop him, till they are seconded [. . .] If the workmen had not a place to retreat into, they would be forced to betake to their heels.’[13]

The debate of Lee’s strike at North Anna continues among historians. The most significant aspect of this argument is that Lee wanted to prevent Grant from shifting around this flank again. He was right to look for these openings and proved that he possessed the coup d’oeil after establishing the inverted V at North Anna. He protected his forces from almost certain defeat. Grant and Lee had their armies back against rivers, and both put themselves in a disadvantageous position in the course of the battle. Although, Grant was right to order corps commanders to entrench themselves after crossing the North Anna River. His priority remained the destruction of Lee’s army, or at least negate his offensive capacity. The Army of Northern Virginia was the center of gravity for Grant, but when positioned at North Anna, their apex rested on Ox Ford. That position was the key to breaking their army. Clausewitz stated that a concentrated force is necessary to take a position that breaks the center of gravity. It explains why Grant sent expedient orders to Burnside to capture the well-fortified position at Ox Ford. Clausewitz also said that “to act as swiftly as possible; therefore, to allow of no delay or detour without sufficient reason.”[14] Ox Ford was the decisive point for both Grant and Lee. All tactical disadvantages were a second priority for Grant.

After the failed Federal effort to take Ox Ford, Grant took into account that any assault upon Lee’s fortified line would be futile without high casualties. He was unwilling to make such a sacrifice; therefore, he sought to flank Lee’s left. The VI and V Corps found that it was not possible given Hampton’s deployment on Lee’s left flank. It is in Grant’s orders to Meade 25th would impress Henri-Antoine Jomini,

Direct Generals Warren and Wright to withdraw all their teams and artillery not in position to the north side of the river to-morrow. Send that belonging to General Wright’s corps as far on the road to Hanovertown as it can go without attracting attention to the fact…. Have this place filled up in the line, so if possible, the enemy will not notice their withdrawal. Send the cavalry to-morrow afternoon, or as much of it as you may deem necessary to watch and seize, if they can, Littlepage’s Bridge and Taylor’s Ford, and to remain on one or the other side of the river at those points until the infantry and artillery all pass… I think it would be well to make a heavy cavalry demonstration on the enemy’s left to-morrow afternoon also.[15]

Jomini believed plans consisted of analyzing maps and picking important positions to capture.[16] Grant utilized these measures at the Battle of North Anna and wanted to find a weak point in Lee’s line without the same sacrifice at Spotsylvania Courthouse. Unfortunately, Hampton’s cavalry protected Lee’s left flank, preventing such an adept plan. The armies of Northern Virginia and the Potomac stared across the field at one another in a tactical stalemate. In order to retain the initiative, Grant shifted his forces against Lee’s right once again. The forces would meet next at Bethesda Church and then clash at Cold Harbor.

How should historians analyze Grant’s decisions at North Anna? His focus on the initiative resulted in a tactical victory on May 23 but put himself in a precarious position as the II Corps remained backed up against the river. If entrenchments were not being used in such a manner, then Lee easily could have driven or destroyed a significant portion of the Army of the Potomac. Ox Ford was a decisive point for both Lee and Grant as it was the apex of the inverted V, but for Grant, it was the critical position that would permit his forces to unite across the North Anna. It is no wonder that he would order Burnside to attempt to take a fortified position. The battle’s significance did not occur during the fighting but lay in Grant’s Hard War policy. This policy required the destruction of Confederate resources without the harm of noncombatants.[17] The Army of the Potomac tore up eight miles of the Virginia Central Railroad on May 25 and deprived the Confederates of valuable economic resources.[18] Lee’s generalship is equally remarkable as he once again turned disaster into a stalemate. He failed to read Grant’s intentions on May 23, but his defense at North Anna should impress any military historian. Although, the question remained, “Could Lee retake back the initiative with Grant continuously engaging his army?” Time would tell.

Bibliography

Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Kansas: Digireads, 2018.

Falkner, James. Marshal Vauban and the Defense of Louis XIVs France. Havertown: Pen & Sword Books, 2011.

Grimsley, Mark. And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May-June 1864. Nebraska: Nebraska Press, 2005.

Grimsley, Mark. Hard Hand of War. United Kingdom: Cambridge university Press, 2008.

Jomini, Antoine-Henri. The Art of War: Strategy & Tactics from the Age of Horse & Musket. London: Leonaur, 2012.

Mackowski, Chris. Strike Them a Blow: Battle along the North Anna River, May 21-25, 1864. California: Savas Beatie, 2015.

Marszalek, John, David S. Nolen, and Louie P. Gallo. The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition. London: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Rhea, Gordon. To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13–25, 1864. Louisiana: LSU Press, 2005.

U.S. War Department. The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington DC: Government Printing Press, 1884.

Venable, Charles. “The Campaign from the Wilderness to Petersburg.” Southern Historical Society Papers, 14 (1876 – 1944).

Endnotes

[1] Chris Mackowski, Strike Them a Blow: Battle along the North Anna River, May 21-25, 1864, (California: Savas Beatie, 2015), 45.

[2] Ibid, 53.

[3] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, (Kansas: Digireads, 2018), 59.

[4] U.S. War Department, The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington DC: Government Printing Press, 1884), 119.

[5] Antoine-Henri Jomini, The Art of War: Strategy & Tactics from the Age of Horse & Musket, (London: Leonaur, 2012), 212.

[6] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, 491.

[7] U.S. War Department, The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 167.

[8] Mark Grimsley, And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May-June 1864, (Nebraska: Nebraska Press, 2005), 138.

[9] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, 492.

[10] Gordon Rhea, To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13–25, 1864, (Louisiana: LSU Press, 2005), 326.

[11] Charles C. Venable, “The Campaign from the Wilderness to Petersburg,” Southern Historical Society Papers, 14 (1876 – 1944), 535.

[12] John F. Marszalek, David S. Nolen, and Louie P. Gallo, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition, (London: Harvard University Press, 2017), 562.

[13] James Falkner, Marshal Vauban and the Defense of Louis XIVs France, (Havertown: Pen & Sword Books, 2011), 35.

[14] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, 571.

[15] U.S. War Department, The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 183

[16] Antoine-Henri Jomini, The Art of War, 58.

[17] Mark Grimsley, Hard Hand of War, (United Kingdom: Cambridge university Press, 2008), 218.

[18] Mark Grimsley, And Keep Moving On, 148.

I understand that battlefield preservation activities at North Ana have enlarged and improved the interpretative experience since I was there twenty years ago. I look forward to a return visit.

It’s well worth a visit. The Confederate works along the left are very well preserved, and a trail takes you all the way to the apex. Unfortunately, trees mostly obscure the view of Ox Ford from the apex.

Hanover County operates the park there. I’ve been there twice and would go again!

https://www.hanovercounty.gov/246/North-Anna-Battlefield-Park

I love this series! Sometimes we get lost in the nuances of the tactical level of warfare (and rightfully so, as how events unfolded on the battlefield are some of the most exciting stories of the war). However, I really enjoy strategic analysis of the war and operational campaigns. This is really excellent!