Myths and Misconceptions of Cold Harbor

There are certain battles which have a lot of misconceptions attached to them. Perhaps one of the most myth-shrouded battles is the 1864 Cold Harbor engagement near Richmond.

Part of the Overland Campaign, it was at the tail end of Grant’s grueling drive across central Virginia. Many readers likely know that one of the biggest myths of Cold Harbor is the estimate of 6,000 (or whatever high number you insert here) killed and wounded in just 30 minutes on June 3. Just not true. Total losses for the entire day were about 3,500, including the morning attack and later fighting. That’s less men than fell in the Union attack at Fredericksburg or Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg.

First, to many of us Cold Harbor seems like a nameless, senseless battle, lacking maneuver and without key landmarks. Gettysburg has its Wheatfield, Peach Orchard, and High Water Mark. Antietam has the Cornfield and Sunken Road. Shiloh has the Hornet’s Nest and Bloody Pond. What does Cold Harbor have?

In fact, in the first few days there was open field fighting and maneuver at Cold Harbor. And there were landmarks on the battlefield named by the soldiers: Bloody Run, the Allison Farm, the Crossroads, Fletcher’s Redoubt, and more. This battle simply has not been studied in the same detail as many others, nor has it been as well preserved, thus the lack of familiarity with these landmarks.

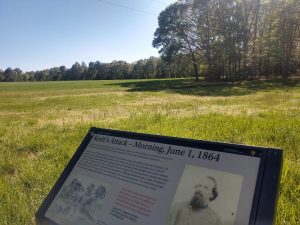

Another misconception is that it was a lopsided Union defeat. It was, in the end. But for the first few days it was touch and go, and in fact it was not such a neat, clean, and easy Confederate victory when you dissect it. On May 31, Union cavalry wrestled the vital Cold Harbor crossroads from Confederate troopers. Then on June 1, a Confederate infantry counterattack failed miserably. That evening Union troops arrived and successfully drove their adversaries back. That makes three Confederate failures within two days, with lots of prisoners taken. No wonder Grant wanted to escalate the battle here.

Once the main battle began, a Confederate counterattack on June 3 led by Floridians failed disastrously, as did smaller attacks against Union troops on June 6 and 7. By then both sides had dug in. One Union observer wrote of the June 6 attack against Fletcher’s Redoubt that, “beyond making a great noise resulted in very little damage.”

So why do we look at Cold Harbor as a Union disaster? These Confederate missteps were overshadowed by the scope and scale of the Union failed assaults. Yet we should not forget that they occurred.

This up another point: To really appreciate Cold Harbor, we must recognize that it was more than June 1 and 3. Much more! The battle lasted from May 31 to June 12—two weeks. Name another engagement that lasted that long, with the armies in constant contact. There aren’t many. Perhaps that why the one- or two- day battles are easier to study; they are easier to grasp.

Those who study the Civil War recognize that Cold Harbor showcased the inefficient system of replacing troops in the Union army. A number of Heavy Artillery regiments joined the Army of the Potomac recently, and fought their first battle here. Converted to infantry and marching and fighting in the field for the first time, they often suffered terribly. Examples include the 300 men lost by the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery and the over 500 lost by the 8th New York Heavy Artillery.

Yet the Confederates were bringing in rookies too, and they suffered just as badly. Both armies needed fresh manpower by late May, and as the Union was stripping its garrisons in Washington and Baltimore, the Confederacy was doing the same thing. New troops joined the Army of Northern Virginia from Florida and South Carolina.

In the days preceding Cold Harbor, South Carolina cavalry suffered terribly at Haw’s Shop and Matadequin Creek, giving ground both times. The 20th South Carolina infantry, larger than the rest of its parent brigade under Col. Lawrence Keitt, failed in their June 1 attack. Florida troops suffered terribly in their failed counterattack on June 3. Again, the magnitude of the Union losses overshadow these shortcomings, but both sides were brining in green troops.

It’s not only the troops we tend to focus on. We often compare generalship in the two armies. Sure, Grant and Meade had to deal with a cautious Burnside and prickly Warren as corps commanders. But let’s not forget that Lee’s corps leadership was suffering by the summer of 1864. Longstreet, his most experienced and trusted commander, was badly wounded in the Wilderness and was out recuperating. In his place was Richard Anderson, who continually came up short. Jubal Early led the Second Corps and was not aggressive enough at times. General A.P. Hill commanded the Third Corps, also with mixed results. All three failed to cooperate at crucial times, like on June 1, 5, and 6 when the Confederates were launching attacks. And JEB Stuart was dead. Lee was desperate for good leadership and wasn’t’ getting it.

Finally, Cold Harbor was not simply a trench warfare engagement, with one side charging senselessly and the other blazing away from cover. Both sides tried innovation. Union troops attempted different attacking formations. They brought in mortars to shell inside Confederate works. They responded by digging out holes behind the trail of their cannon to elevate them, turning them into mortars, to return fire behind Union trenches. The men of the 148th Pennsylvania began a tunnel, which they planned to pack with explosives to blow a hole in the Confederate lines. Sound familiar? The Crater almost happened here. But the army pulled out before it was completed.

Rather than simply a senseless bloodbath, Cold Harbor was a two-week long, intense, and complicated engagement with maneuver and innovation on both sides. Although not as well preserved as many other battlefield sites, groups like the Richmond Battlefields Association and American Battlefield Trust are working to change that. Both have saved more land in recent years and along with Richmond National Battlefield Park, have expanded what is available to the visiting public.

As far as attacking the long discredited gross exaggeration of Union casualties during the uncoordinated assault of June 3, Bert is preaching to the choir. In pointing out the greatly improved conduct of the Union cavalry in the week leading up to the assault, Bert’s spot on. Of course, their performance up to that point was mediocre at best, depriving Meade of a valuable reconnaissance asset. The Confederate’s loss of Stuart was arguably offset by the promotion of Hampton, who would prove his worth at Trevilian Station. I am somewhat surprised that the successful evening assault of June 2 by Ewell’s Corp against Burnsides was omitted from the narrative. Sometimes, in attempting to set a record straight, one can overplay a hand.

Thanks for your comments, John. The June 2 Confederate attack on Burnside was not successful, and I’ll admit I neglected to include that. My goal was to highlight some lesser known parts of the battle. Many of us know about the lack of good leadership on both sides and the reality of the June 3 attack.

There has been a consistent effort recently to diminish the magnitude of the Union’s defeat at Cold Harbor, despite general consensus for the previous century +. June 3rd is universally regarded as Grant’s biggest mistake, including by Grant himself, and a big one by any measure. Ignoring Grant’s own assessment seems disingenuous. Of course there were mistakes and failings on both sides, and it was not just the one assault on June 3rd, but by far the gravest errors were Grant’s and Meade’s. Regarding the numbers of casualties/dead, they were 12,738 killed/wounded/missing/captured for the Union, and 5,287 for the Confederacy, for the entire campaign. This is cleverly referred in the Wikipedida summary as a relatively smaller loss for the Union, since they had about twice the troops there. I admire this attempted dodge, but one might think having twice the troops would have led to a resounding victory, not a frustrating defeat, or at best, draw. Regarding June 3rd, losing even ‘just’ 3,500 men in less than an hour, versus virtually none for the opposition, ordering another assault which was refused by his men, and then leaving the dead and wounded there for three days while contesting the terms of truce to allow retrieval, ignoring all known protocol, does not reflect well on Grant. And he knew it.

Grant didn’t say it was his “biggest mistake.” He said he regretted the last assault was made, because no advantage was gained for the loss of life.

And the 3500 lost was for the entire day, not in less than an hour.

Thanks. I agree, this was perhaps Grant’s worst moment of the war, and he should definitely take plenty of blame for what happened. I didnt’ mean to downplay the scale of the Union debacle, it was huge, just wanted to shed some light on lesser known parts of the battle.

I agree with Carson. It’s really something when one needs to read Grant’s Memoir’s of the battle to get a more balanced view.

“Leaving the dead and wounded there for three days while contesting the terms of the truce…”

And that’s another myth. It was actually the wounded in one specific part of the field, and Lee was just as much to blame for the miscommunications and delays.

Dan is right. Grant never called it his “biggest mistake” because he was not in the habit of admitting mistakes. That he regretted it means it must have hit him hard.

To be fair very few generals ever are in the habit of admitting error, and the best are good at shifting blame or at least negative attention elsewhere such as what happened to Lew Wallace after Shiloh. All in all it is one way they get promoted. Not that always works. Just ask John Pope.

By 1865, John Pope became one of the most senior general officers in the US Army, a noted Indian fighter, and had a long career in the service. The loss at Second Bull Run was a minor issue for him in his long career. Not defending him, just stating the facts.

Grant may have regretted the attack knowing the outcome, but he should have attempted it 100 out of 100 times. Had it been successful, he would have shattered the ANV with their backs against a significant river. They would have lost all of their artillery and given the lack of an easy retreat route, the US Army would have captured larger formations. What if they had been able to attack the day prior? What if Meade hadn’t just phoned it in and instead of only 9 brigades engaging, the general attack was truly a general attack? There was a high potential tactical price, but the strategic prize was worth it.

“Regrets” and “mistakes” are not the same thing. Maybe confederate generals had no regrets for the numbers of southerners killed for no reason. Grant regretted lives lost for no gain.

Grant’s/Meade’s losses during any one of the days of the opening attacks on Petersburg on June 15-18 make June 3 look like a picnic. I blame Meade mostly for those disastrous and uncoordinated assaults. Meade’s army suffers roughly the same number of casualties in four days outside of Petersburg (11,300) than he does during nearly two weeks of fighting at Cold Harbor (12,700).

“There has been a consistent effort recently to diminish the magnitude of the Union’s defeat at Cold Harbor, despite general consensus for the previous century”

No there hasn’t. There’s been an effort to look at the “conventional wisdom” that – like so many oversimplifications about the ACW – became accepted “fact” without it being questioned. Cold Harbor is one example. Anybody who thinks that Gordon Rhea was trying to work some public relations “spin” for Grant by making a long overdue examination of the facts and concluding that the accepted story was an exaggeration doesn’t know much about the author. And nobody who is serious about assessing the state of historiography – or anything else – is not going to rely on Wikipedia.

correction: ” … is going to rely ….”

So unfortunate that the area in the Bethesda Church sector of the battle was not preserved early on. Most visitors aren’t aware of the fighting that occurred there, so it’s easy for them to assume that the “real” fighting only took place around the trenches near the Cold Harbor Visitor’s Center.

So true—there is absolutely no place to park at the intersection of Polegreen/Walnut where Pegram’s Virginia Brigade attacks Warren’s line on May 31st and at the old site of Bethesda Church is an elementary school and beyond that more B.S.

Thank you for this article. I knew Cold Harbor was more than a couple days, but I thought that Grant’s experience at North Anna led to his overconfidence at Cold Harbor. At North Anna, it was noted by the Union that the rebs gave up the south bridge over the river with less than expected resistance. But they didn’t see this as a brilliant trap. In time, when the Union high command realized their weak position, they pulled out of the trap but they assumed Lee’s army must be too weak to fight, for they could see that the rebs had the advantages of interior lines and an enemy that couldn’t support from one wing to the other. Little did they know how sick Lee was at the time, he himself being worn down by the command decisions of constant fighting, near disasters (“Lee to the rear!”), crummy weather and his own self discipline, imo.

What I hear Bert saying through his last two articles, Antietam and Cold Harbor, is that certain aspects of a campaign only make sense in context. Bert has everyone thinking.

Maybe an ECW writer might take Cold Harbor on to add to the series and the public’s knowledge?

Hey Joe,

The battle of Cold Harbor has been done, by Dan Davis and Phil Greenwalt. It was in fact one of the earliest books in the series. See here: http://emergingcivilwar.com/publications/the-emerging-civil-war-series/ecw-series-hurricane-from-the-heavens-by-daniel-davis-and-phillip-greenwalt/

I have it and read it when it came out – not sure why I forgot…thanks Ryan