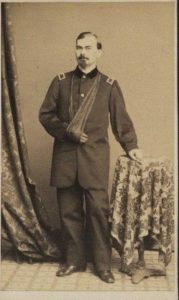

Fallen Leaders: General Max Weber at Antietam

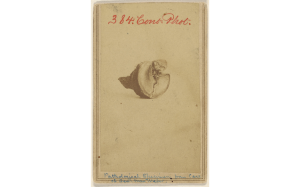

One late spring day in 2013 a farmer plowing his field in Martin County, Minnesota noticed a small white porcelain object poking out of a furrow. He stopped the tractor, climbed down, and retrieved the curious artifact, which was slightly larger than his thumb. It was in remarkably good condition with a full color image of a dashing young officer named “Colonel Max Weber.” The farmer had no idea who Max Weber was or how the pipe bowl ended up in rural Minnesota.[1]

Mass-produced commemorative pipes called reservistenpfeife were all the rage among late nineteenth century German immigrants. Their popularity peaked during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. German American commanders went out of their way to procure fresh bread, Rhine wine, lager beer, and tobacco for troops who longed for the familiar comforts of the Fatherland.

While most American Civil War enthusiasts can recite the names of German American generals like Carl Schurz, Franz Sigel, August Willich, and Peter Osterhaus among others, Max Weber is less well-known. In his day, however, Weber was famous, especially in his adopted home state of New York. While many of the estimated 214,000 German Americans who were to fight for the Union vowed to “fight mit Sigel” when the war began, Weber had already done that.

Born in the town of Achern in the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1824, young Max Weber followed his father into military service. He was educated at the military academy at Karlsruhe, graduating in 1843 and was commissioned a lieutenant in the Grand Duke’s army. He joined Sigel in defecting to the republican cause in 1848 and in 1849 commanded Sigel’s advance guard in a doomed series of skirmishes against a much larger force of Prussians and others from the German Confederation. Like many so-called Forty Eighters, Weber fled first to Switzerland, then London, and finally New York where he managed the Hotel Konstanz on William Street.[2]

Weber, Sigel, and their fellow revolutionaries dreamed of returning to their homeland to fight yet again for popular rule. In the meantime, they formed a local Turnverein. Ostensibly a social club, most of its members were radical socialists in their politics, maintained rigorous physical fitness through gymnastics, and conducted military drills to maintain combat readiness. When Lincoln’s call for troops came following the fall of Fort Sumter, German Americans across the North were among the first to enlist.

On May 16, 1861, Weber was appointed colonel and commander of New York’s Turner Rifles, later part of the Twentieth New York Infantry. Like other German American volunteers, Weber’s troops were older, more fit, and better-trained than their native-born counterparts. They made their mark early in the war on August 27, 1861, when they landed under fire at Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, seizing an important fort at the inlet, thus helping to stifle Confederate efforts to run the Federal naval blockade. Weber was commissioned a brigadier general on April 28, 1862 and participated in the capture of Norfolk, Virginia the following month. In September, 1862, Weber was awarded command of the Third Brigade in Brigadier General William H. French’s Second Division of the Second Army Corps in the Army of the Potomac as Union General George McClellan prepared to respond to the Confederate advance into Maryland. They met the enemy west of Antietam Creek north of the town of Sharpsburg in what is considered by many to be the bloodiest single day of the war.[3]

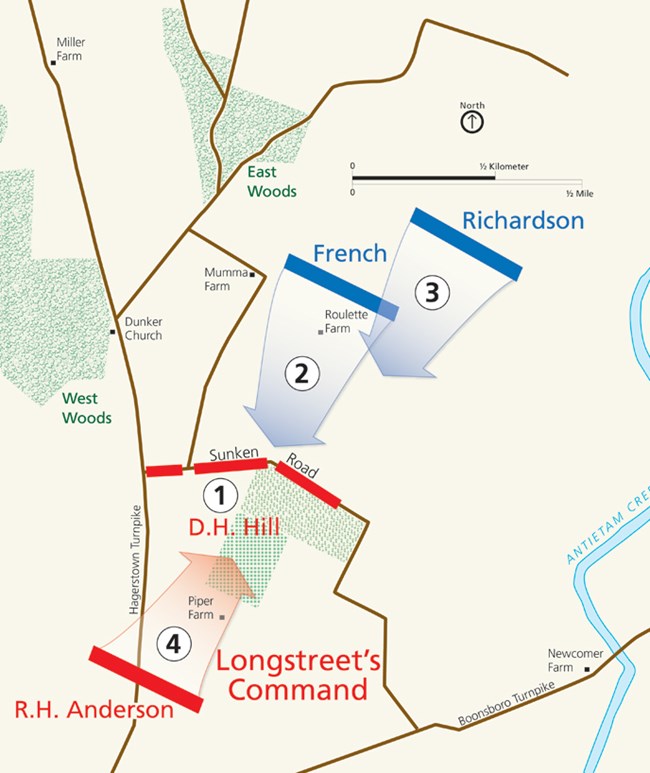

Weber’s infantry brigade, consisting of the Fourth New York on the left, Fifth Maryland in the center, and First Delaware on the right, led French’s division in an assault on the Confederate division of General D.H. Hill, strongly positioned in two lines behind a barricade of fence rails in a sunken road four feet below ground level. A third rebel line loomed in the rear on a rise that allowed them to fire over the heads of their front-line troops. At approximately half past nine in the morning, Weber’s brigade had dispatched Confederate skirmishers near the Roulette and Mumma farms and advanced to within thirty paces of the enemy. Then the slaughter began in earnest.

About 450 men in Weber’s brigade fell within five minutes. Eight out of ten company commanders in Colonel John W. Andrews’ First Delaware were killed or wounded. All of their color guards were killed, as were all of the field officers’ horses. The Fifth Maryland lost 166 men including three successive commanders who were wounded. Their entire color guard also perished. Forty-four soldiers of the Fourth New York died in the hail of rebel bullets. In all, Weber’s brigade lost more than a third of its men in their stubborn assault on what became known locally as “Bloody Lane.”[4]

General Weber and his assistant adjutant were attempting to rally the Marylanders when both were wounded. As he raised his right arm in command, a single rebel ball shattered his elbow, carrying three inches of his radius away before exiting his forearm. Assistant surgeon Charles Heiland of his beloved Twentieth New York removed Weber’s elbow joint on the field before transferring him to a Sixth Corps hospital where he convalesced for three months. He would never regain the use of his right arm. Weber’s broken radius head was saved and became a celebrated relic in surgical circles.[5]

Like many wounded general officers, Weber returned to active duty in a series of desk jobs, including assignments in the Shenandoah Valley under Sigel and General David Hunter and as garrison commander at Harpers Ferry during the Jubal Early raid of July 4 to 7, 1864. He resigned his commission on May 13, 1865 and led a long postwar life filled with accolades and accomplishments, including a short stint as the U.S. counsel in Nantes, France. Weber’s status as a war hero earned him a series of lucrative civil service appointments, including jobs as an assessor and Internal Revenue Service collector in New York City. His continued sponsorship and involvement with local Turners helped him gain wealth and position in the city’s large German American community. When he died in 1901, Weber’s estate was worth in excess of $80,000.[6]

As for the Weber pipe bowl, its origins remain a mystery. Perhaps a tobacciana expert will help uncover its history. Was it produced before Weber’s promotion in 1862 or fashioned later to commemorate his leadership in New York’s Turner Rifles? There were 44 veterans on the 1883 pension roll of Martin County, Minnesota. Did one of them once own the pipe? Perhaps more interesting is the importance of officers like Weber in Civil War memory. Nearly forgotten today, many of these men were war heroes and leaders in their postwar communities. Weber and other 1848-9 revolutionaries who recruited fellow European immigrants to the Federal army should be better understood. Many fought for principles that went well beyond simply preserving the Union. As Rhode Island Lieutenant Governor Samuel G. Arnold remarked in 1861 after describing Weber’s regiment at the capture of Fort Hatteras: “The idea of liberty, which is bounded by no land, native of no clime, the inheritance of no particular people, no nation, country, kindred or color under Heaven, this cause is the cause of constitutional liberty and the rights of universal humanity.”[7]

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020).

Notes:

[1] https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/85654-col-max-weber-civil-war-pipe

[2] New York Times, 16 June, 1901.

[3] Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography, 1889, 405.

[4] Antietam on the Web, “ BGen William H, French’s Official Report,” https://antietam.aotw.org/exhibit.php?exhibit_id=54, “Col John W. Andrews’ Official Reports,” https://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?officer_id=271

[5] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. (1861-65.), Part 2, Volume 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1876), 848.

[6] New York Times, 16 June, 1901, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 2 October, 1901.

[7] The Liberator, 13 September, 1861.

Very interesting. I am interested in the German Americans who fought incivil war. I got interested after reading the civil war historical novel Cain at Gettysburg by Ralph peters which is excellent. I then read two historical books entitled Under the Crescent Moon which refers to the first corps of the army of the Potomac in which many German Americans served. Unfortunately they were vilified after Chancellorsville and Gettysburg for alleged cowardice .in fact they fought dogged defensive actions in both battles until being overwhelmed by superior numbers of rebels. One of my personal heroes is not German but a Pole who fought with the Germans – Kriz. I can’t remember how to spell his polish name.

Wlodzimierz Kryzanowski

Like Bob LaPolla, I appreciate favorable treatment of German American contributions to the Union cause. There are too many untold stories of quiet professionalism like the Weber story.