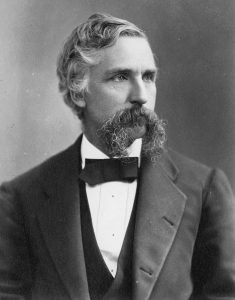

Fallen Leaders: Joshua Chamberlain lost “the gleam of white light”

The Civil War killed Joshua L. Chamberlain on Tuesday, February 24, 1914, almost nine years after “the gleam of white light … shed upon my soul” flared into eternity.

Since a Confederate bullet punched through his groin from right to left at Petersburg on Saturday, June 18, 1864, Chamberlain had suffered immeasurable pain, endured several failed surgeries, and probably become impotent. A Victorian gentleman did not discuss such intimacy (as most modern men would not), but the recurring medical troubles caused by the wound would make any intimate relations difficult (and perhaps impossible) between the general and his wife, Fanny.

Decades plagued by eye trouble, she literally lost sight of him. “Fanny is blind,” Joshua informed his sister Sally (“Sae”) in April 1899. Fanny “exhausts all her energies” seeking a cure, even turning to a “magnetic doctor who dares not tell her that he cannot help her.”

Fanny adjusted to her sensory prison as Joshua lobbied President William McKinley for appointment as the Portland customs collector, a financially lucrative sinecure. Backing his campaign with petitions signed by Mainers notable and obscure, Joshua learned that party politics would relegate him to surveyor of the Port of Portland, paying $4,500 a year.

The Chamberlains needed the income, so he accepted the position. The work would be easy, with “no responsibilities, no duties, no power, no part in the governmental representation, and requiring no ability,” the general commented. “I ought perhaps to be thankful to get it.”

He left Fanny in late autumn 1900 to tour southern Europe and Egypt (ostensibly for his health), and afterwards the new job physically separated the Chamberlains. His position seldom required his presence, yet Joshua moved into the two-story, wood-framed house that he purchased at 499 Ocean Avenue in Portland and went to his office almost daily.

He could have stayed with Fanny in Brunswick and occasionally traveled to work in Portland. As he had done so often since enlisting in midsummer 1862, Joshua consigned his domestic responsibilities to others. No doubt heart-felt, his letter-attested love for Fanny evidently did not extend to becoming her full-time caregiver.

He did come home now and then, and occasionally Fanny and her attendant visited Portland, but for Joshua Chamberlain, there was always the next southbound train to catch from Brunswick.

His absences and her blindness apparently affected her psyche. “Your affliction seems to have made you hard, rather than tender,” with “these physical deprivations affecting the mind and spirit,” Joshua told Fanny in early July 1902. “This must not be.

“You need love … that is exactly what you can have if you will receive it,” he said.

Sapped by ill health himself that July, Joshua thought a “[long] contemplated yacht trip” would boost his morale. His physician, Dr. Abner O. Shaw, “says I must have a respite, & ought to be off three weeks,” but the general would not take the time.

Depression tightened its grip on Fanny. Her “gloomy mood …. seems so darkly to envelope you,” Joshua observed in February 1903. Offered “any proposition intended for your help,” Fanny focused “on the disadvantageous things” rather “than the helpful or agreeable things.”

Fanny slipped, fell, and broke a hip on Friday, August 4, 1905. Absent in Portland on her birthday a week later, Joshua penned a praise-filled “word of loving greeting with thanks that we have been so long spared to each other, & life has been so rich in blessings.”

But Fanny deteriorated; “I fear the issue,” Joshua wrote in early September. Shortly before her death on October 18 (perhaps the very day), he poured his heart and love into a letter in which he admitted, “But Fannie — may God bless you — do not think that I can ever forget in my darkest hours the gleam of white light you have shed upon my soul.

“May God bless you as He blessed me when I was suffered to you,” Joshua wrote, acknowledging his flowing tears (“these stains upon the paper”).

He and his surviving children, Grace and Wyllys (as Harold preferred to be known), buried Fanny in the family plot at Brunswick’s Pine Grove Cemetery. Returning to Portland, Joshua immersed himself in his work, veterans’ affairs, and the Grand Army of the Republic.

His Petersburg wound and wartime malaria kicked up; the wound suppressing his immune system and leaving Joshua prone to various infections. Yet he still got around in Portland; a local newspaper remembered him as “the little old soldier, blue eyed and gray moustached,” encountered by many people while walking the downtown streets.

Doctor Shaw and Dr. Morris Townsend had struggled in flickering candle- or lamplight after sunset to find and tie the severed blood vessels from which the general’s life had ebbed that Saturday, June 18, 1864. Shaw now looked after Joshua, even accompanying him to Gettysburg in mid-May 1913 as planning proceeded for the battle’s 50th anniversary.

The trip beat up the frail general, and Shaw assured him “it would be extremely hazardous for me” to return to Gettysburg for “the Celebration and Reunion” that July. The calendar slipped into January 1914; that month a “particular disease … caused me such unspeakable agony,” but the general was gradually recovering as Shaw and other “Doctors and nurses” cared for him.

Grace and Wyllys watched as their father died from his war wound about 9:30 a.m., Tuesday, February 24, 1914 at 499 Ocean Avenue, Portland. The Civil War had killed him; they would take their father home and bury him beside his beloved Fanny.

Under the “Cause of Death” on Chamberlain’s death certificate, Shaw wrote neatly, “Chronic Cystitis and Ch.[ronic] Posterior Urethritis caused originally by gunshot wound.”

Sources:

- Jeremiah E. Goulka, editor, The Grand Old Man of Maine: Selected Letters of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 1865-1914, (Chapel Hill, NC, 2004), pp. 68, 177, 184-185, 194-197, 210-214, 270-271, 281-287

- Joshua L. Chamberlain death certificate;

- Brave Soldier Crosses River to Pitch His Tent for All Time with Great Commander, Portland Daily Press, Wednesday, February 25, 1914

How very sad. His book “The Passing of the Armies” reveals a bright and observant intellect. While I do not side with the Union’s version of the War, Chamberlain was perhaps the most worthy individual involved, in my opinion, in his frame of reference as a Brigadier General.

While he might be a bit overrated, he should still be considered a great hero who fought for his country. It’s sad to see that he had to endure decades of physical pain, and the emotional pain of what appears to be a crumbling marriage in his final years.

He was always a patriot.

Tom Crane