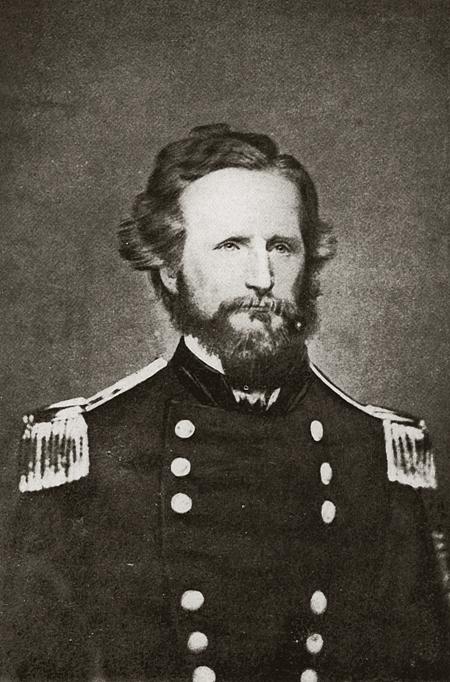

Fallen Leaders: Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon, Part II

Following the fateful Planters’ House Hotel meeting in St. Louis on June 11, 1861, the newly-promoted Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon took action immediately to oust the Missouri State Guard and secessionists from the state. At that meeting, negotiations to maintain peace between the two sides over the state failed and sent the state into armed conflict. After returning to Jefferson City, Governor Claiborne Jackson made a call for 50,000 volunteers in the immediate wake of the Planters’ House Hotel meeting. Lyon’s strategy was to order “a movement of a portion of the troops under my command to Jefferson City and in the direction of Springfield, Mo., for the purpose of breaking up the hostile organizations which I had reason to believe had been formed in those parts of the State to resist authority of the Government.”[1] With 1,700 Federal volunteers and Regulars, Lyon embarked via the Missouri River towards the state capital at Jefferson City, while the remaining soldiers of his newly-created Army of the West moved toward the railhead at Rolla and on toward Springfield.

Lyon’s strategy was simple: outmaneuver the pro-secessionist government and Missouri State Guard by securing the vital Wire Road, Southwestern Branch of the Pacific Railroad, and Missouri River. These movements would create a pincer, forcing the secessionists toward the southwestern corner and eventually out of Missouri. Through this plan, Lyon hoped to destroy and punish his enemy. Governor Claiborne Jackson had made “war upon the United States,” which made it “necessary for me to move up the river.”[2]

By June 17, 1861, Lyon’s Army of the West had captured Jefferson City without a fight and that morning, landed just six miles below the river town of Boonville. There, “the governor had fled and taken his forces … where, so far as I could then learn, a large force was gathering.” After marching about three miles toward Boonville, “the enemy [roughly 500 strong] was discovered in force,” but quickly fell back after Lyon’s troops held “high and open ground” and poured heavy fire on their positions.[3] By 11:00am, Federal forces had successfully captured Boonville and routed the Missouri State Guard in the first, though small, land battle of the war west of the Mississippi River.

While pro-secessionist forces fled south, Lyon was concerned about the Missouri State Guard being reinforced by Confederate volunteers under Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch. A consolidation of these forces, according to himself, could “reach 15,000” of “well armed, and prepared” Confederate troops, compared to his much smaller 5,400.[4] In addition, throughout the summer of 1861, his own forces had continued to dwindle due to expiring enlistment terms.

By mid-July, Lyon established his headquarters at Springfield, Missouri, located in the southwestern region of the state, and intended to hold as long as possible. Sitting along the vital Wire Road that connected Fort Smith and St. Louis, Springfield was an excellent location for protecting the Federal lines of supply and communication, while also allowing for quick maneuvering in case of an attack. Lyon was already aware that the Missouri State Guard under Price had been training in the region and was already in communication with McCulloch. The chances of a consolidation between the two forces were highly likely and Lyon’s prediction of the enemy’s strength at 15,000 was not far off from reality, which was 12,000 (2,000 of them unarmed).

Lyon was deeply concerned at his army’s lack of supplies, dwindling numbers of troops, little pay, and exhaustion. In late July, he also received news of Brigadier General Gideon Pillow and Major General Leonidas Polk’s advance into the southeastern “Bootheel” of Missouri. Major General John Fremont of the Department of the West, believing the Bootheel and southern Illinois were far more important to the Federal grand strategy, ignored Lyon’s requests. By August, if Lyon did not either take the offensive or receive reinforcements from Fremont, he and his army would have to fall back to the railhead at Rolla, Missouri, and thereby cede much of their gains made in Missouri.

In the early days of August, Lyon and a portion of his Army of the West moved out from their base at Springfield to determine the location and size of enemy troops. Unable to locate the main enemy body, he called a council of war with his four brigade commanders and determined to fall back to Springfield. On August 7, after receiving intelligence that the enemy planned an imminent attack and was encamped in the Wilson’s Creek valley southwest of Springfield, Lyon held another council of war. While many of his subordinates believed they needed to fall back to Rolla, Lyon was determined to attack. Once again, he was not about to let the prime opportunity to attack the enemy slip between his fingers. He exclaimed to his staff about the possibility of a retreat, “Not until we are whipped out!”[5] Over the course of the following two days, Lyon held other councils of war. While it was evident “that we must retreat,” he was still convinced they should “throw our whole force upon [the enemy] at once, and endeavour to rout him before he can recover from his surprise.” Additionally, Lyon knew that he “can resist any attack from the front, but if the enemy moves to surround me I must retire.”[6]

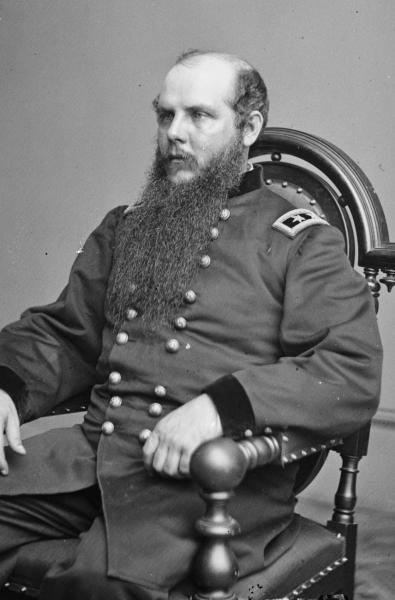

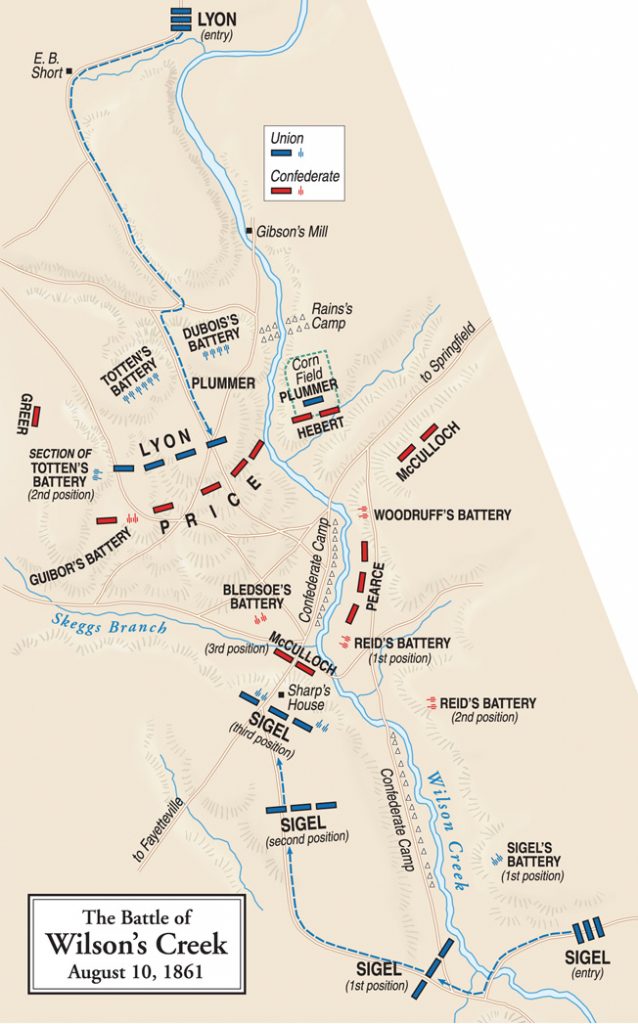

On August 9, however, commander of the 2nd Brigade Franz Sigel approached Lyon in his headquarters. He had a bold plan to divide the Army of the West in two – Lyon to lead one wing and Sigel the other. Lyon’s wing would strike the enemy’s position from the north, while Sigel would swing to the south and strike the rear. Though the rest of the high command was vehemently against the plan, he believed it could work and he trusted Sigel’s reputation to carry it out successfully. Lyon needed this bold plan to work to bolster his reputation, strike a decisive blow to the Southerners, prove to Fremont he could still win on the battlefield without reinforcements, and fulfill his duty to at least try. On the night of August 9, the Army of the West departed Springfield to rendezvous with destiny.

At 1:00am on a rainy August 10th morning, Lyon’s wing of the Army of the West encamped just within sight of the enemy camps. Around the same time, Sigel’s force encamped along the Wire Road south of the Southerners. According to Lyon’s chief of staff Major John Schofield, Lyon had premonitions of his own death while encamped that early morning. “I will gladly give my life for a victory,” said Lyon.[7]

At dawn on August 10, Lyon’s wing advanced into line of battle and pushed south toward the enemy camps. About one thousands yards in advance of the camps, Lyon’s troops made contact with some Southern troops, specifically foragers scavenging for breakfast. Soon, along a ridge to their south, the Federals engaged Southern cavalry and forced them south with ease. To secure their left flank and the Wire Road, Lyon deployed Capt. Joseph Plummer’s Regular Battalion across Wilson’s Creek to the Ray Cornfield. Meanwhile, Lyon’s wing continued to push south and soon occupied the battlefield’s most prominent high ground, “Bloody Hill.”

To the south, Sigel’s men moved northward toward the Southern camps after hearing the roar of musketry and artillery from Lyon’s wing. He surged forward toward a position of high ground overlooking a tributary of Wilson’s Creek, named Skegg’s Branch, and began pouring shot and shell on the camps. Sigel mistakenly believed Lyon was successfully driving back the Southerners toward his position. Instead, a regiment of gray-clad troops approached Sigel’s position. Thinking these soldiers were members of the 1st Iowa Infantry, who in fact wore gray, Sigel allowed them closer to his position. By the time the soldiers in gray were in close range, they fired a volley into the Federal position, forcing them to crumble and flee. The fight on the southern end of the battlefield was all but lost.

Back on the northern end of the field, Lyon’s line on Bloody Hill stood their ground against repeated attacks by troops of both McCulloch’s force and the Missouri State Guard. Directing his troops on the front lines, Lyon was dangerously close to enemy fire, yet did not move to the rear. He was soon struck in the calf of his right leg, forcing him to bandage the wound. Lyon’s white and gray horse, who he had to dismount in the heat of battle, was struck and killed. Shortly after his first wound, Lyon was struck again, this time grazing the right side of his head. The pain of his wounds and loss of blood forced the commander to sit down in the rear of his line. A handkerchief was wrapped around his head and was given some brandy for the pain. Nearly giving up from the pain and exhaustion, it was Schofield who inspired Lyon to go to the front and lead one more charge against the oncoming Southern advance up Bloody Hill.

After he mounted an orderly’s horse, Lyon moved forward and spotted a gap in the Southern line. Rallying the men of the 2nd Kansas Infantry and waving his cap, Lyon shouted, “Come on, my brave boys, I will lead you! Forward!” Just as Lyon turned his head to his boys, a volley from the enemy lines erupted. He was struck in the left chest, through his heart and both lungs.[8] In a state of shock, Lyon tried to dismount his horse, but went limp and began to fall. His orderly, Pvt. Albert Lehmann, caught him from his saddle and lowered the fallen commander down. Bleeding profusely and in his orderly’s arms, Lyon found the strength to say his final words: “Lehmann, I am going.”[9] A moment later, the Union’s first general officer – and martyred hero – was dead.

Command of the Army of the West passed onto Major Samuel Sturgis, the next highest-ranking officer on the field after Sigel and his wing fled the field. With oncoming assaults on Bloody Hill, no word from Sigel, and low ammunition, Sturgis made the difficult decision to retire from the field and fall back towards Rolla and St. Louis.

During the withdrawal off Bloody Hill, Lyon’s body was somehow left behind in the chaos. Though Sturgis ordered the fallen general to be placed in a wagon for transport to Springfield, Lyon’s body was mistaken for a line officer because he wore a captain’s frock coat during the battle. It was an officer of the Missouri State Guard who found him and brought the body by ambulance to Price’s headquarters. There, Surgeon Samuel Melcher of the 5th Missouri Infantry (Sigel’s Brigade) took over the care of Lyon’s body and had it escorted to Springfield. The next day, Lyon was placed in a walnut coffin and sent to Congressman John Phelps’ home for care and then burial. One week later, an ambulance from St. Louis arrived, disinterred the body, and escorted it to St. Louis.

When they arrived in St. Louis on August 26, Lyon was then laid in state at Fremont’s headquarters, where thousands of mourners came to see the Union war hero. Just two days later, his body went on a funeral procession via train back home to Connecticut, where he was buried next to his deceased parents and two brothers.

In the years following Lyon’s death and the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, veterans of the battle had the chance to reflect upon his legacy and role in securing Missouri for the Union. Private Eugene Ware of the 1st Iowa Infantry later wrote, “I think that if he had not been killed he would have succeeded beyond his most sanguine expectations … He was a man capable of grasping great occasions and doing great things, and at the same time a wasp to those around him.”[10] Major John Schofield, who later received the Medal of Honor and became the Commanding General of the Army, wrote in 1892 that, “Lyon’s heart could not endure the appeals of those who claimed his protection, and he cheerfully gave his life for the chance of a victory.” He went on, saying, “what gratitude is due from every loyal soul to the name of the brave soldier who so willingly gave his life for his friends.”[11] Senator Lafayette Foster of Connecticut in front of Congress said, “Brave men shed tears over him; Connecticut mourns him as a true and gallant son; the nation deplores the loss of a patriot and a hero.”[12]

Today, historians debate the legacy of Nathaniel Lyon. From a crazed sadist, radical Unionist, and narcissist; to war hero, selfless leader, patriot, and one who put cause over everything else, Lyon has a complex legacy among scholars. His actions, though bold and daring, helped secure Missouri for the Union. By securing the Missouri River, capturing Jefferson City, forcing out the militia from St. Louis, protecting the St. Louis Arsenal, and establishing control over the Wire Road and Southwestern Branch of the Pacific Railroad, Lyon had begun the process of Federal occupation of the state. Only in 1862 and 1864 were there serious threats to the Union cause in Missouri by Confederate forces. Lyon had set the stage for Missouri under Federal control.

On the other side, however, Lyon’s actions were dangerous to a tense situation in Missouri. By parading his Missouri militia prisoners through the crowded streets of St. Louis, he recklessly exposed prisoners, his troops, and civilians to what became a fatal episode. The Camp Jackson Affair split the state and forced many to side with the pro-secessionists. Also, a failure to compromise at the Planters’ House Hotel prevented any form of peace and instead forced Missouri into armed conflict. These early, bold actions certainly contributed to Missouri having over one thousand actions, engagements, and battles during the war. Only Virginia and Tennessee had more.

If Lyon had survived the Battle of Wilson’s Creek and made it through the war, he no doubt would have been successful on the battlefield. But, it is hard to say if he could have survived politically or advanced through the ranks of the Lincoln Administration’s high command. Over the course of his military career prior to the Civil War, he made many enemies and only a few friends. He was a martinet, tough, focused, and ambitious. His own troops were sometimes unsure what to think of him, because he was not too focused on developing bonds with his men. Nonetheless, Lyon was focused, determined, decisive, and unafraid. He took immediate action, was bold, demanding, put country over self, and was a natural leader in combat. Thomas Snead, Price’s Chief of Staff at Wilson’s Creek and Lyon’s former adversary, stands out as one of the most revering accounts of the Union general. In his book, The Fight for Missouri, Snead eloquently wrote, “Lyon had not fought and died in vain … By wisely planning, by boldly doing, and by bravery dying, he had won the fight for Missouri.”[13] Indeed, he had.

Sources:

- Report of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, June 22, 1861, in OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 11.

- Report of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, June 22, 1861, in OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 12.

- Report of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, June 22, 1861, in OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 12.

- Report of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, August 4, 1861, in OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 3, 48.

- Holcombe & Adams, An Account of the Battle of Wilson’s or Oak Hills (Springfield, MO: The Greene County Historical Society, 1985), 22.

- Eugene Ware, The Lyon Campaign (Topeka, KS: Crane and Company, 1907), 304; John Schofield, Forty-six Years in the Army (New York: The Century Co., 1897), 40-41.

- Schofield, Forty-six Years, 43.

- Christopher Phillips, Damned Yankee: The Life of Nathaniel Lyon (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 255.

- Ibid., 256.

- Ware, The Lyon Campaign, 339-340.

- John M. Schofield, “Lyon’s Heroic Death,” December 29, 1892, The National Tribune, Washington, DC, Library of Congress.

- Ashbel Woodward, Life of General Nathaniel Lyon (Hartford, CT: Lockwood & Co., 1862), 360.

- Thomas Snead, The Fight for Missouri: From the Election of Lincoln to the Death of Lyon (New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1886), 302-303.

A fellow from my home area of Grovespring, MO (near Springfield) was named General Sigel Snow. Not Franz, General. He went by his middle name.

Good series on Lyon.

The vast majority of Missouri citizens were moderates on the issues of slavery and secession. Governor Jackson was very pro-secession, but he had no political support for secession. The state convention in early 1861, called by the legislature, at the governor’s behest, “to consider the relations of the State of Missouri to the United States” did not include a single secessionist among the 99 elected delegates from the 33 state senatorial districts. Resolutions voted by the convention clearly reflected the political middle ground as reflected in the JOURNAL AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE MISSOURI STATE CONVENTION (1861). Nathaniel Lyon made two major mistakes; the first being his egregious, tone-deaf declaration of war on the still-loyal state of Missouri. The newly-formed Missouri State Guard (MSG) became an ally of the Confederate States Army by virtue of a common enemy. The attack by the Union Army on Missouri incented tens of thousands of citizens to join the MSG.

Lyon’s army soon occupied strategic Springfield and was threatened by a Southern coalition of McCullough’s Confederate Army, comprised of Louisiana and Texas units, Pearce’s army of southwest Arkansas, and the MSG. This force outnumbered Lyon’s army 2 to 1.

Lyon’s second major mistake was attacking the Southern force southwest of Springfield, compounding the error with a flawed battle plan. At the urging of Sigel and other brigade commanders, he divided his army to attack a much larger force from separate directions. The Southern force held the main Union army in check while they focused on Sigel, sending him fleeing back to Springfield, and then turned in full fury on Lyon’s main force. Such a battle plan reflects Lyon’s flawed tactical capability as a former infantry company commander (about 100 soldiers) who now commanded a much larger force of four brigades. Lyon was killed exhibiting outstanding field leadership, but his army was soundly defeated.

Before the battle, Lyon had three options: attack, defend-in-place, or retreat to Rolla. Springfield was strategic to holding southwest Missouri, and I strongly believe that defending-in-place was his best option. It would have been very difficult for the Southern force to have defeated an entrenched Union army at Springfield. The attack exposed his smaller force to possible annihilation by an ably-led, superior force.

Although Lyon was a West Point graduate, class of 1841, his commissioning as a second lieutenant of Infantry indicates that he ranked in the lower part of his class. The West Point Military Academy was established by Congress in 1802 to train engineer soldiers. The top graduates were commissioned in the Corps of Engineers (e.g. Robert E. Lee, Douglas MacArthur, et al), the middle ranking men in the Cavalry, and the lowest ranking class segment as Infantry.) This may be an indication of lesser military proficiency of Nathaniel Lyon and a factor in the loss at Wilson’s Creek.

Actually, Lyon graduated 11th in a class of 50 so he was definitely not on the lower end of the class.