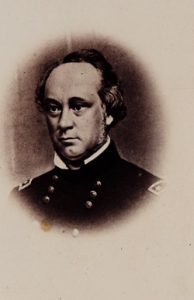

Civil War Fallen Leaders: Major General Henry Halleck

Some of you might be bumfuzzled as to why General Halleck is included in this series. After all, he did not die in the war–but his reputation certainly did! I have done the same things many of you have done–seen Halleck as a sort of military joke. Then I read Walter Stahr’s Stanton and soon revised my opinion. I live in central California–closer to San Francisco than Santa Barbara. Even when I lived further south, all I ever heard was how California had nothing to do with the Civil War. Those of us who were reenactors at Fort Tejon kept our fingers crossed every time we went to an event back east. We dreaded the thought of being thrown out by Eastern stitch-counters. But, of course, they did not take into account that West Coast stitch-counters might be equally serious about what was then called “the hobby.” Life moved on, I left reenacting, and here I am today, ready to tell you what I learned about Halleck in a book about Stanton.

Some of you might be bumfuzzled as to why General Halleck is included in this series. After all, he did not die in the war–but his reputation certainly did! I have done the same things many of you have done–seen Halleck as a sort of military joke. Then I read Walter Stahr’s Stanton and soon revised my opinion. I live in central California–closer to San Francisco than Santa Barbara. Even when I lived further south, all I ever heard was how California had nothing to do with the Civil War. Those of us who were reenactors at Fort Tejon kept our fingers crossed every time we went to an event back east. We dreaded the thought of being thrown out by Eastern stitch-counters. But, of course, they did not take into account that West Coast stitch-counters might be equally serious about what was then called “the hobby.” Life moved on, I left reenacting, and here I am today, ready to tell you what I learned about Halleck in a book about Stanton.

Henry was the third child of fourteen, born in central New York. He ran away from home early on and was raised by his uncle, who lived in Utica. His uncle managed to get young Henry into West Point in 1835. During the next four years, Halleck found his true calling–being an academician. Military theorist Dennis Hart Mahan took the young man under his wing and became his mentor. While still a cadet, Halleck was allowed to teach classes. He graduated in 1839. leaving his intellectual safe place behind and graduating third in his class of 1839. He spent several years in New York City, improving harbor defenses. This resulted in his first book, a Senate report titled Report on the Means of National Defence. His effort so impressed American military god General Winfield Scott that Halleck was rewarded with a trip to Europe in 1844. There he studied European fortifications and the elite French military. He also was promoted to first lieutenant.

Henry Halleck returned home to much acclaim and immediately began his second book, Elements of Military Art and Science. In addition, he gave twelve lectures on the topic at Boston’s prestigious Lowell Institute. Elements, published in 1846, was one of the first books expressing American military professionalism. It was extremely well-received by Halleck’s colleagues and became one of the definitive tactical treatises used by officers in the Civil War. The volume also gave thirty-one-year-old Henry Halleck his nickname “Old Brains,” not yet a derogatory term.

The Mexican-American War had begun, and Halleck was assigned to duty in California, a territory on the verge of statehood. Getting to California was a tricky proposition. Of the three choices–across land, across the Isthmus of Panama, and around Cape Horn–Henry Halleck chose to take a seven-month trip on the sloop USS Lexington around the tip of South America known as Cape Horn. The army assigned him to be aide-de-camp to Commodore William Shubrick.

Here is our young (31) hero, unmarried and still possessing most of his hair, on a fantastic voyage halfway around the world, and what did he choose to do with his time? He decided to translate Henri Jomini’s Vie politique et militaire de Napoleon from French to English. Although this furthered his academic reputation, I am thinking that it did little for him socially. Halleck spent several months in 1847 constructing fortifications in California. He finally saw combat during the capture of the port of Mazatlan by Shubrick in mid-November. Commodore Shubrick trusted Halleck so much that he made him lieutenant governor of the city and awarded him a brevet promotion to captain, claiming it was for Halleck’s “gallant and meritorious service.” At this point, Halleck’s military career seemed like it certainly might amount to something.

Up-and-coming California was about to get even better for Henry Halleck. General Bennett Riley had been appointed the governor-general of the “California territory.” Riley demanded that the brilliant young writer, Henry Halleck, join his staff and appointed him military secretary of state. This made Halleck the governor’s personal representative at the 1849 convention held in Monterey, on the central coast. One of the tasks given to the men at the convention was creating a state constitution, necessary before California could be considered for statehood. Halleck became one of the principal authors of the document. The California State Military Museum notes that Halleck:

was [at the convention] and in a lone measure its brains because he had given more studious thought to the subject than any other, and General Riley had instructed him to help frame the new constitution.”

During the convention, his name was bandied about as one of the two men to be chosen to represent the new state in the U. S. Senate but was not selected.

When Halleck was writing the California Constitution and being fawned upon by the elite of a very prosperous new state, he also joined a law firm in San Francisco. Halleck, Peachy, & Billings became so successful that Henry resigned his army commission in 1854. He was getting rich quickly due to his work as a lawyer and a land speculator. In addition, Halleck obtained several thousand pages of official documents concerning the Spanish missions and Land Grants, which created his reputation as an expert on California colonization.

This handsome, bright, successful young man married the beautiful Elizabeth Hamilton in 1855. She was the granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton and the sister of Union general Schuyler Hamilton. Elizabeth was the belle of the season when she made her debut. Their only son was born in 1856.

As a farsighted San Franciscan, Halleck was responsible for building the Montgomery Block, San Francisco’s first fireproof building. It was home to lawyers, businessmen, and later, several of the city’s writers and newspapers. In addition, he was a director of the Almaden Quicksilver Company in San Jose. Quicksilver, or mercury, was necessary to separate gold from the surrounding minerals. He was president of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. This grandly named enterprise ran between San Francisco and San Jose. He developed land in nearby Monterey and Carmel, and owned the 30,000 acre Rancho Nicasio in Marin County. And, Halleck being Halleck, he stayed involved in military affairs. By 1861 he was a major general in the California militia. How could life possibly get better for Henry Halleck? The simple answer is–it couldn’t.

Unfortunately, in August 1861, Halleck responded positively to Winfield Scott’s pleas for him to return to the east. Once there, he accepted the rank of major general in the regular army, and it all began to go downhill. He managed to keep his money and his wife, but his reputation was beyond resuscitation by the end of the war. President Lincoln called him a “first-rate clerk.” Today, no one respects Henry Halleck for much of anything. Poor guy.

Suppose he had just stayed in California, living the dream. In that case, we might all be sharing a glass of delicious, fruity, oak-aged cabernet from the historic cellars of the Halleck Winery in Marin County while we read Emerging Civil War.

In my view, Halleck was a “first rate clerk”

Thanks for fleshing out this Civil War leader, whose career is usually just reduced to a sound-bite.

Henry Halleck, Major General of the California Militia in 1861, was called to Washington D.C. after Brevet-LGen Winfield Scott’s offer of supreme command of the Union Army was rejected by Robert E. Lee. Because the message by Pony Express required days, and the journey from California by ship was measured in weeks, and “someone” had to take supreme control after the Federal disaster at Bull Run… the position of General-in-Chief of the Army was offered to President Lincoln’s choice of candidate, Johnny-on-the-spot George McClellan; and after McClellan accepted the role, Winfield Scott retired. Halleck arrived in Washington to find MGen McClellan in overall command; and with President Lincoln NOW requiring an immediate replacement of the Commander in Missouri. Halleck journeyed to St. Louis in November 1861 (and U.S. Grant used the “command vacuum” before Halleck arrived as opportunity to launch an amphibious operation against Belmont.)

Major General Henry Halleck took command of the Department of Missouri (which stretched from the Trans-Mississippi, east to the Cumberland River of Kentucky) and initiated active measures to 1) secure his base at St. Louis; 2) drive organized Rebel forces out of Missouri; 3) initiate offensive operations south, down the valley of the Mississippi River; 4) turn (or subjugate) powerful Rebel Fort Columbus. Using generals Grant, Pope, Prentiss and Curtis, (and Navy Flag Officer Foote), Halleck achieved these goals… and was rewarded in March 1862 with expansion of his command to include Buell’s Department of the Ohio. Now in command of the Department of the Mississippi, Halleck vacated his role as distant puppet-master and took to the field to direct offensive operations that ultimately resulted in the near-bloodless occupation of the strategic railroad junction at Corinth Mississippi. THIS was the high point of Halleck’s career. And for convincing Stanton and Lincoln that he had “knee-capped Rebel operations in the West,” Halleck was called to Washington in July 1862 and rewarded with elevation to General-in-Chief of the Army… And it was all downhill from here.

[If Henry Halleck had died during the trip east in July 1862, he would be remembered today as “a great General, whose career was cut short.” Timing is everything…]

Halleck’s sidelining of Grant after Shiloh and his mis-handling of the Corinth campaign with its long delay and allowing the escape of rebel troops is hardly a highlight of his career. Yes, Corinth was a rali center but if supported by Halleck,instead of undermined, Grant undoubtedly would have had it much sooner and bloodied the Confederate army, as well. I agree with Meg on the high point of Halleck’s career.

Going by today’s money, Halleck would have been a very, very rich man. Imma missin that wine!

U.S. Grant was sidelined after Fort Donelson, after confronting Buell at Nashville without authorization. Grant was returned to field command in mid-March, and was then surprised ten miles away from Pittsburg Landing on 6 April 1862 by Albert Sidney Johnston’s Army, audacious enough to do the unexpected and leave the fortified Rebel base at Corinth. [Both Grant and Sherman believed Johnston had no choice but to wait for the Union Army to come to him.] Bloody Shiloh so enraged Northern moms, dads and widows of fallen soldiers that MGen Grant was demanded, via letters and newspapers, “to be removed from command for incompetence.” Halleck shielded Grant by temporarily removing Grant from command, and assigning him as “second-in-command” to Halleck. After the horror of Bloody Shiloh, the North was relieved by the near-bloodless Victory at Corinth, orchestrated by Henry Halleck. Major General Halleck relied on false reports of subordinates to “gild the lily” and proclaim a situation [the disintegration of the Rebel Army in the West]… that was soon revealed to be mere wishful thinking. But, by then, Halleck and his most trusted lieutenant, Major General John Pope, had been called to Washington: elevated to more senior positions. And U.S. Grant was left as the most senior Federal Major General in the West; and Grant was able to gather his soon-to-be Army of the Tennessee (first recorded use of that label on 25 OCT 1862) and operate mostly without supervision (his closest supervisor was Henry Halleck, at Washington.)

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

“U.S. Grant was sidelined after Fort Donelson, after confronting Buell at Nashville without authorization. Grant was returned to field command in mid-March, and was then surprised ten miles away from Pittsburg Landing on 6 April 1862 by Albert Sidney Johnston’s Army…”

That’s what happens when you jerk a subordinate around like a puppet. Halleck should have supported the subordinate who had just handed him a victory at Henry and Donelson. Instead, Grant had the misfortune of having a haughty colleague (Buell) and a back-stabbing superior (Halleck). It’s definitely harder to succeed without support from coworkers and managers.

I did not know that Henry Halleck grew up in Utica, NY (near where I live and work). I do know the history of Dan Butterfield in Utica and have seen some his artifacts at the local historical society. On a side note, not sure why, but General James Ledlie is buried in Utica.

Great comments all–I am still missing that wine, though. Thanks.

I once argued Henry Halleck would have been Time’s Man of the Year of 1862.

What a great reply! Someone should mock up a cover.

Best I can do on short notice:

https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv6bonn/page/257/mode/1up